The Canadian transportation situation after

World War II

Is someone else going to eat the CPR's lunch?

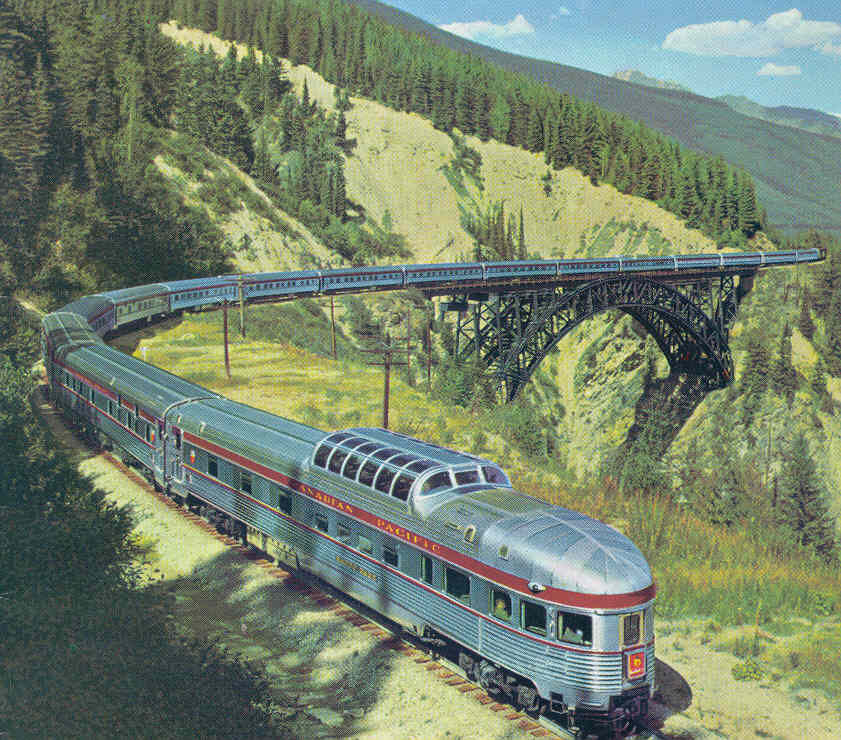

CPR "The Canadian"

By 1946, the Canadian railways had "owned" most of the long distance

passenger business for 60 years.

In total, the Canadian railway network included about 43,000 miles

of track. Railways remained the most efficient way to move large numbers

of people around a continent-sized country at reasonable prices. Personnel

returning from World War II were keeping the railways busy during this

period.

By this time, Canada had 125,000 miles of surfaced roads and

over three times that in gravel and dirt roads. Even with wartime manufacturing

restrictions on the production of new private automobiles, 11.5 million

Canadians were driving 1.5 million cars on those half-million miles

of Canadian roads. The completion of the the Trans-Canada Highway was

over a decade away. In practical terms, you still couldn't get there from

here.

However, it was another mode of passenger transportation that

was in the process of eroding the railways' control over long distance

travel.

In 1946, both the government-owned CNR and the exchange-traded

CPR had their air transportation components : Trans-Canada Air Lines

and Canadian Pacific Air Lines respectively. To quote an executive

of the CPR regarding the railway boardroom attitude toward the airline

in the 1940s and 1950s: " ... we expected to keep the railway operating

profitably and were skeptical of the airline ever contributing much

to the parent company's profits."

In an earlier time, those who built Canada's railways were

daring risk takers ... often with the Government's deep pockets

backing up the enterprise. A new railway was good for local property

values, good for business, and generally good for the country. In some

cases, the risk worked out poorly, and a Government separated the entrepreneurs

from their dreams - generally when the financial situation or political

"optics" were not helpful to the Government's staying in power.

With the old "building in the wilderness from scratch" challenges

long since dealt with, the shiny-shoed boardroom class which had since

evolved on the railways was about to meet the ultimate risk takers ...

The Development of Aviation in Canada, 1914-1946

Sometimes to avoid the mud and death of the World War I trenches

and often for the adventure, Canadians joined Britain's newly hatched

Royal Flying Corps. Between 1914 and 1918, using rapidly evolving technology

and combat tactics, some like Major W.A. Bishop, VC, DSO, MC ended the

war alive and as Canadian heroes.

Billy Bishop "a man incapable of fear" - according

to one American ace - and a Nieuport 17

After World War I, this spirit of innovation and risk taking

found its natural match in Canada's geography. Here was a country with

vast expanses of unmapped wilderness in which untold mineral wealth

probably lay. Certainly most of the country lay beyond economical reach

of railway technology, and the centuries-old practice of travel by canoe

and portaging was due for replacement.

First travelling in "flying canoes" (wooden-hulled flying boats)

exploration, and later the systematic aerial photography and mapping

of remote Canada, was begun by adventurous aviators. Floatplanes - ski-planes

in winter - also ferried in geologists, engineers, miners, equipment

and supplies.

They could land on water or snow - and Canada had an endless

inventory of lakes to use as runways!

- Heated hangers in which to repair winter breakdowns?

- Northern weather reports?

- Radar guidance and traffic control?

- Government provided Search and Rescue?

- No - the early bush pilots were pretty much on their own ...

flying only by basic cockpit instruments, experience, and their finely-tuned

senses. Sometimes following an "iron compass" (a railway line) helped them

reach their destinations.

A Canadian bush plane equipped with floats.

A Canadian bush plane equipped with floats.

In 1928, surveys for a trans-Canada airway were begun - an aerial

highway between east and west. The Depression put much of the more

expensive development on hold, but unemployed workers were offered some

of the more basic preparation work.

In 1937, Transport Minister C.D. Howe said that "Canadians

were insistent in demanding the establishment of a direct Canadian

[air mail] service" - rather than having western-Canadian airmail travelling

aboard American airmail aircraft. So Trans-Canada Airlines (TCA) was born

and the systems needed to support it (air fields, passenger terminals, training

standards, navigation charts, meteorological services) were brought up

to snuff.

While the CPR and its airlines might have been part of Trans-Canada

Airlines at one point, things didn't go well : it seemed the government

was determined to have a national air carrier, with

break-even finances, working as a monopoly

. The CPR-owned airlines were allowed to operate domestically in areas

where the TCA had no interest.

By 1939, daily passenger, air mail and air express services

were being operated by TCA between Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver with

various stops along the way. Canada's involvement in World War II 1939-1945

changed priorities. Supporting the war by carrying vital priority freight,

mail and key military personnel became the new mission of TCA.

During the Second World War, Canada became "The Aerodrome of

Democracy" (thanks for that title, FDR) with the establishment of the

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Vast and far beyond

the range of enemy planes, Canada was an ideal site for training aircrew.

Over 130,000 aircrew, from pilots to air gunners, graduated from the

107 schools of the BCATP.

Besides Australia, New Zealand, Britain and Canada, students also

came from the US (officially at war later in 1941) and the occupied

countries of Europe. Canada paid for 75% of the program. The Canadians

who graduated constituted about 25% of the strength of the RAF and also

formed 45 Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons overseas.

Many of the RCAF personnel were assigned to RAF Bomber Command. The

official figures were not known to them at the time, but these airmen had

little statistical chance of surviving their 30 sortie "tours" in the deadly

night skies of Europe.

Air Marshal W.A. Bishop, Director of Recruiting, Royal Canadian

Air Force

Air Marshal W.A. Bishop, Director of Recruiting, Royal Canadian

Air Force

visiting RCAF 411 Squadron (Spitfires) in England,

1942

After all this - after the Great Depression and World War II - there

was one positive outcome ...

Canadians now had the ability to really get going on civil

aviation:

- All kinds of infrastructure used by the BCATP : airfields,

hangars, weather offices, guidance beacons.

- Ferry pilots who had repeatedly delivered new two and four-engined

Canadian-manufactured bombers across the Atlantic Ocean - travelling from

Canada; to Gander, Newfoundland; to Britain. There was no traffic control

guidance back then - a compass and "star shots" were all crews had for navigation

across the ocean.

- Bush pilots who had supported feverish wartime prospecting

for new mineral resources - including uranium.

- Experienced RCAF pilots and crews, many of whom would be discharged

and available for airline training after the war.

- Significant warplane manufacturing experience, and experience

maintaining all the BCATP trainer aircraft.

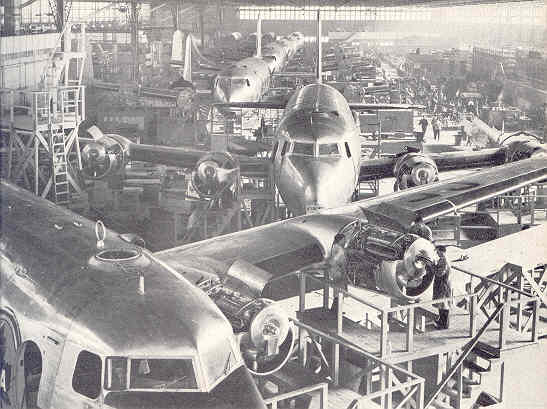

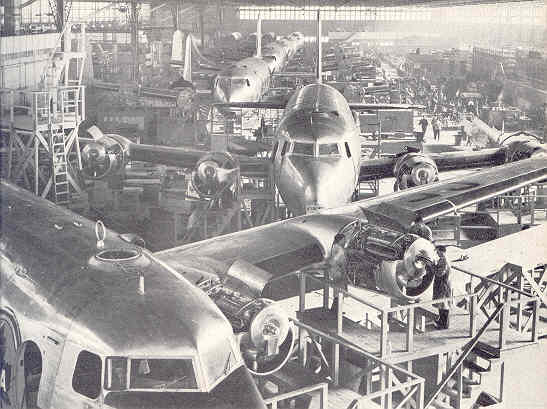

At Canadair in Toronto, TCA passenger planes are assembled

circa 1948.

At Canadair in Toronto, TCA passenger planes are assembled

circa 1948.

Note the circular hole in the cockpit roof - a "glass" dome will be

fitted here to permit celestial navigation.

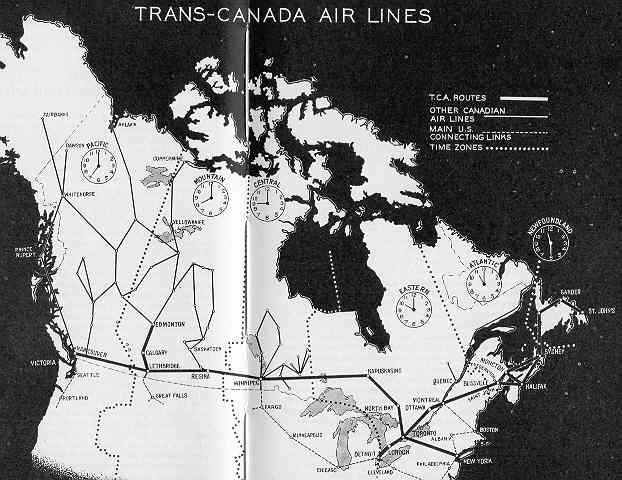

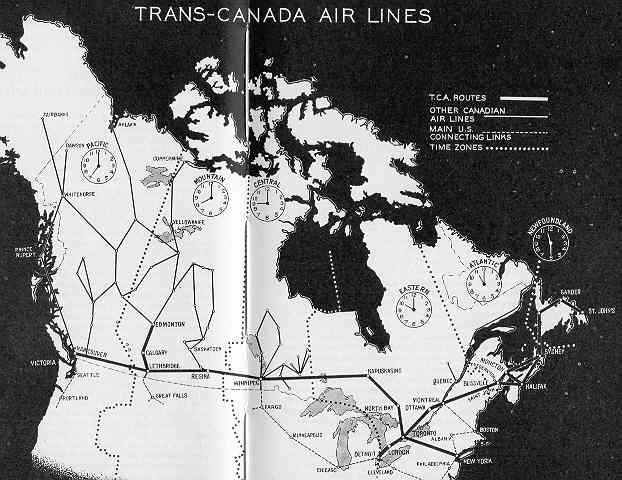

TCA covered any domestic route it thought was worthwhile, as well

as trans-Atlantic, Pacific and service to the Caribbean.

Where permitted,

TCA would also fly into the US.

This is what things looked like right after World War II. You

can probably assume that many of the "other Canadian airlines" were owned

by the CPR.

Aerial "highways" in Canada, 1946

Aerial "highways" in Canada, 1946

Canadian Pacific Airlines in the bush.

Take it easy with the dynamite, boys.

In 1946, according to the Government of Canada:

"Thousands of miles are interpreted as hours of distance;

far flung communities have been drawn close together.

TCA has brought

to Canada a new vision of unity, a new vision of the future."

A TCA Douglas DC-3 in flight in 1946. The first prototype

had flown in 1933.

From wood, cloth and wire - to brushed, stressed-skin

aluminum carrying 14 passengers coast to coast 25 years later.

But what was happening on the rails?

Canadian Pacific Railway's "The Canadian"

(I'm giving the ending first for dramatic effect and pathos.)

Only 16 years after its birth, the final great effort by the CPR

to save its eroding long distance passenger market would be abandoned by

corporate executives, unloved, at the doorstop of the federal regulator.

And for almost a decade, the feds booted the foundling basket

containing The Canadian back to the curb - and told CP Rail

to keep the train rolling.

Canada's last great long distance passenger train was genuinely

Canadian Pacific and Canadian in many ways.

Ironically for proud Canadian nationalists, its inspiration and

principal manufacturing were American.

The Zephyrs and Shotwelding

Passenger trains in the 1920s were pulled by heavy, black, smoke-spewing

locomotives which left a layer of black dust on the window sills of the

trailing passenger cars. The windows opened because most of the cars had

no cooling systems. Air conditioned sleeping cars often used circulating

meltwater from large ice blocks and little electric fans so summer travellers

might be less uncomfortable.

The new streamlined shapes used in aircraft design were capturing

the public's imagination in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Among railroad

executives in the US, the less complacent saw the potential threats to their

passenger business from aircraft and autos ... and the potential marketing

opportunities if they played to this desire for silver, streamlined vehicles.

Railways and locomotive builders were working

on using diesel-electric technology in locomotives.

The Budd Company of Philadelphia had patented a process for welding

stainless steel.

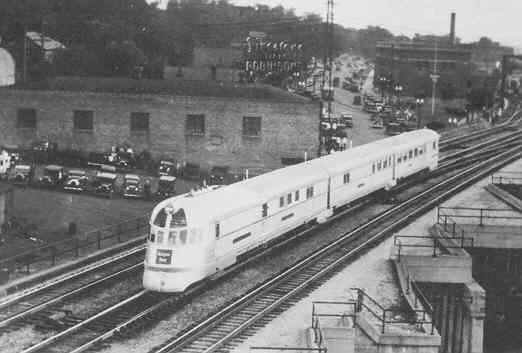

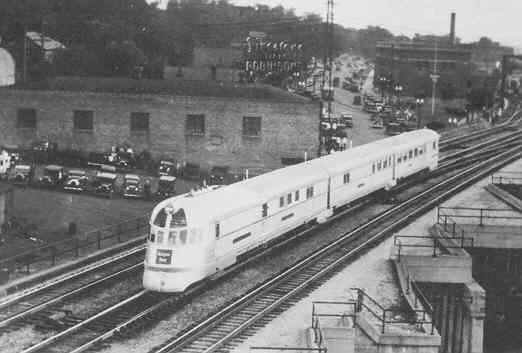

An innovative result was the Pioneer Zephyr

(ZEF fer).

In May 1938, this Zephyr trainset is averaging

78 mph on a special speed trial run between Denver and Chicago - 1015

miles.

Shotwelding - some details

- Stainless steel passenger car exteriors require very little

maintenance and no periodic painting.

- Conventional welding ruins the anti-corrosion properties of stainless

steel.

- Shotwelding was patented in the early 1930s.

- In shotwelding : two pieces of stainless steel were joined

into one uniform piece of stainless steel by attaching two electrodes

on opposite sides of the desired weld location. Then, a precisely calculated

amount of current was run for a precisely calculated instant of time between

the electrodes through the spots to be joined.

- Shotwelding produced a stronger structure than rivetting, and

made the attractive uniform silver skins of modern passenger equipment

possible.

The Pioneer Zephyr - some details

- Railroad : Chicago, Burlington and Quincy - "The Burlington

Route"

- Top speed : 110 mph

- Passenger capacity : 72

- Motive power : 600 hp diesel-electric powering two axles

- This was an "articulated" trainset which shared

wheelsets between the cars to save weight. Railways

usually overbuilt stuff and the Zephyr was unusually light and fast. The

Zephyr cars were coupled over those shared wheelsets and

the trainset could not be made longer or shorter to meet traffic demand

like other railway equipment.

- It was not designed to be compatible with the huge quantity

of traditional rolling stock available at the time.

- The locomotive engineer was in a very exposed position

if there was a level crossing collision with a truck. Fortunately there

is no record of an engineer ever complaining after such a collision.

- It probably rode like a little red wagon on a slab sidewalk,

but it was shiny and fast and captured the imagination of the Depression-era

public.

- To some extent it set the standard for the external appearance

of modern passenger equipment.

"Zephyrs" proliferate

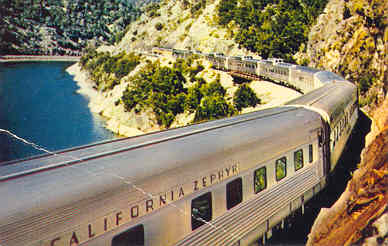

Luxurious, standard coupling, smooth riding, electrically air-conditioned

Budd-built passenger cars were used on the train named the California

Zephyr, operating between Chicago and Oakland (2500 miles) beginning

in 1949. Special observation "dome cars" were included in this train consist

and it travelled via several different railroads on its route. Silver

streamlined "zephyr equipment" was common and quite famous in the late

1940s, and the 1949 California Zephyr is seen by many as

the high point of the zephyr era.

The California Zephyr in California's Feather

River Canyon.

Notice there are 4 "Vista-Dome" cars behind the Western Pacific locomotives.

On its westbound trip, the train travelled mainly on the lines of the Burlington;

Rio Grande; and Western Pacific -

with the eastbound California Zephyr covering these roads in reverse order.

The CNR and CPR had nothing like it.

The CPR's gamble

Early in 1953, the Canadian Pacific Railway did a "me too", called

up Budd in Philadelphia and ordered 173 stainless steel cars for a new

train named "The Canadian". (The first choice for a name

was "The Royal Canadian" but perhaps there was malice at the palace about

the idea. It would have been a violation of protocol to use such a name without

young Queen Elizabeth II's permission.) The CPR also added to their roster

of diesel locomotives to get the project rolling.

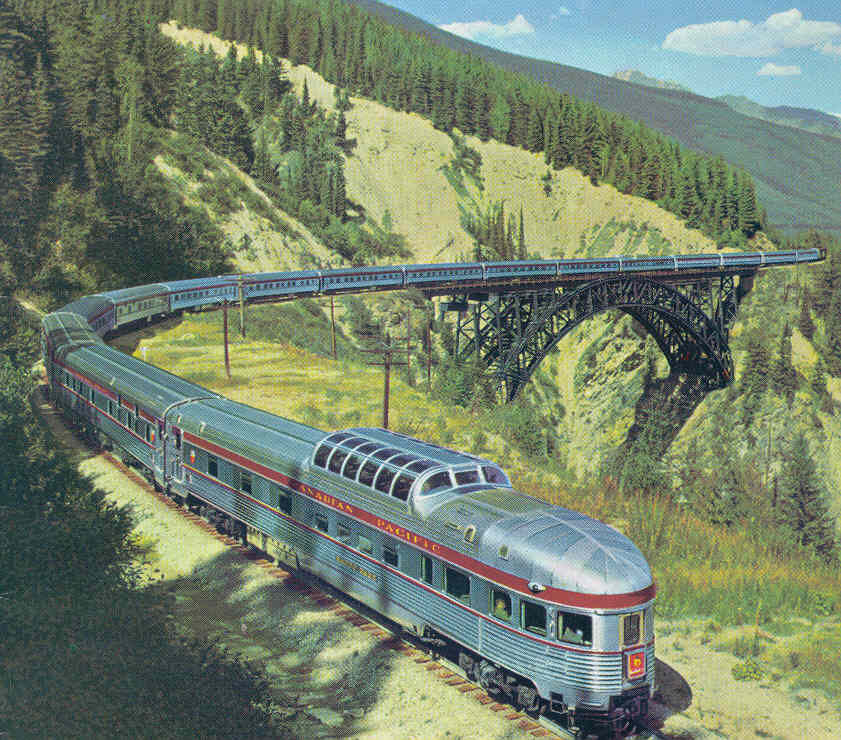

At Stoney Creek Bridge, here is a typical CPR publicity photo of

an eastbound train of the new zephyr, I mean Canadian

, equipment with a dome car on the tailend.

Near the headend, at the far end of the bridge, are three old sleeping

cars with ordinary painted steel sides and old-style clerestory roofs -

but they are dressed up with the special Budd stainless steel plating.

They are doing their best to adapt and be "modern".

As a "North American Zephyr", this train was unique

in the sense that it was operated "across the continent" - Montreal to Vancouver

- by and on one single railway. The CNR operated trains on the same transcontinental

scale, but they didn't buy brand new equipment in the 1950s to create a completely

"new concept" as the CPR did.

Railway infrastructure is capital intensive - a physical

"road" must be built and carefully maintained forever.

Particularly during the two world wars, aviation technology developed

very quickly.

Canadians became proud of the bush pilots, the RCAF, and Trans-Canada

Airlines

as part of their modern national identity.

It was easy for the federal government to throw its full support behind

aviation in Canada.

It was politically attractive to support magically fast travel

on modern equipment.

In addition, those symbolic contrails in the sky from sea to sea

and far into the arctic

would be much cheaper to finance than the steel rails had ever

been.

In the 1950s, the diehard railroaders of the CPR gambled,

giving transcontinental passenger rail service

the brilliant sunset they felt it deserved.

Back to sitemap