Hay on a Dairy Farm

Hay wagon, baler and tractor

Hay wagon, baler and tractor

Warning : This page contains historical information from my happy high school summers working on a dairy farm ...

and much older information if I thought it

might be interesting for readers.

Therefore, you are cautioned that this information - like me - is about 40 years out of date and for amusement purposes only.

For important decisions on dairy husbandry, be sure to consult your local agronome.

And a respectful tip of the hard hat to you !

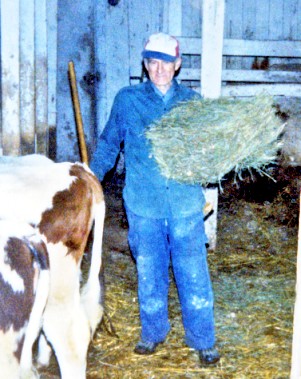

Me on a return visit to the farm in 1978 ...

when I was still up to date and reliable.

And a respectful tip of the hard hat to you !

Me on a return visit to the farm in 1978 ...

when I was still up to date and reliable.

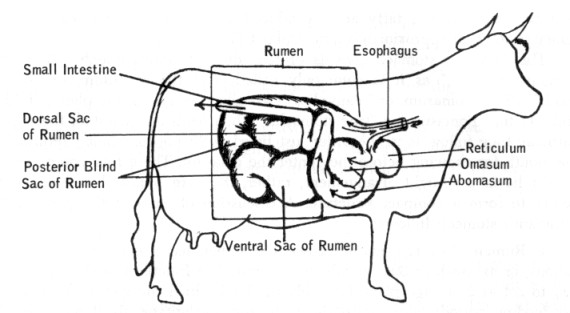

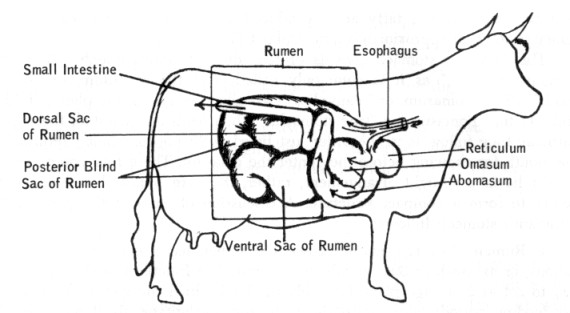

A remarkable gut ... and its refinement

Wild cattle wandered around on

grasslands in herds. Their digestive systems were specialized in

obtaining the nutrients they required for growth, reproduction and general health from what they could find to eat there.

Cattle - including dairy cows - did not evolve as predators ... running

after, fighting, killing, and eating other animals.

Consequently, their

guts had to be able obtain protein from non-animal sources.

Then one day, humans became involved in domesticating cattle and developing them for meat and/or milk production.

Dairy cattle were selectively bred to produce females which were good

at producing large quantities of milk rich in the desired nutrients -

historically it was fat ; today protein is also important. As with

selective breeding programs for other species ... many other qualities

were also deemed desirable.

A practical

example ... when you crouch down beside a 1/2 ton beast to pull on its tender parts ... docility is an important quality.

How do cows obtain protein?

Unlike pigs and chickens which have only a single stomach ... cattle and

sheep are ruminants who spend all day ruminating on things.

In the rumen are trillions of bacteria, yeasts and protozoa which live

on the grasses and other feeds a cow eats.

A warm dark spot is a great

location for micro-organisms to grow and they reproduce every 30

minutes or so.

Their shedding proteins - and, sadly their little

micro-organism corpses when they die - are digested and absorbed as raw

materials for the cow's own protein factories.

The end.

Even more detail on bovine digestion

Cowspit does not have digestion enzymes in it, but it does have enough buffering agents to keep the rumen at a neutral pH.

Cows produce about 120 pounds of saliva per day. If you have ever eaten

dry hay ... or dry shredded wheat ... you know why

this volume is handy.

dairy cow: rumen reticulum omasum abomasum

dairy cow: rumen reticulum omasum abomasum

All day as they eat, cows are constantly

adding to the blend of vegetable matter, liquids and micro-organisms in

their rumen. The cow's rumen can hold up to 300 pounds of material.

From time to time, the cow returns quantities of the rumen's contents

to its mouth for further grinding with its molar-like teeth to

physically break up the plant material. This chewing increases the surface area of its cud ... so

the microbes can work more effectively once the material returns to the rumen.

After all of this ruminating, the cow partly digests the plant fibre ... and the process also yields amino acids, proteins and B-complex vitamins.

The rumen's

processes also produce significant quantities of the following waste products : carbon

dioxide, methane and ammonia.

Next we move through the other stomach sections :

Reticulum : With a

honeycomb-like lining this section traps heavy objects, including

stones and bits of metal a cow might eat for amusement.

Omasum : Having many folds of

tissue, this section squeezes the food, thus breaking it down a little

more and helps reduce its water content.

Abomasum : Just like yours, Mandrake !

... this is the cow's "true stomach" where proteins are

digested ... with fat, starch and cellulose rolling on toward the small and large intestines.

Digestion is now complete

... with digestion complete

... the dairy farm summer student

capably moves in with shovel, broom, quicklime and wood

shavings.

What to feed your cows

Generally speaking, 25% of a cow's milk production characteristics are based on

genetic factors.

"Proven sires" who all live and party together in a big central barn somewhere ... and artificial insemination ...

are used

to optimize purebred breeding.

Today, embryo flushing and storage and embryo transfer techniques may also used ... and so on into the future ...

Good-bye Bossy ... Hello Dolly.

The other 75% of a cow's milk production characteristics are attributable to environmental factors ... the most important one being nutrition.

Roughage is any feed containing a large amount of fibre.

Cattle evolved to survive on grasses and other plants, so it is

necessary for them to have enough roughage to "keep things moving" through their guts.

Summer pasture ; silage (which is self-pickling corn or grass ... or other crops) ; and hay are common sources of roughage.

When cattle are growing, or a cow is pregnant or lactating, care is

taken to ensure that additional necessary nutrients are provided.

A concentrate containing a blend of grains and other foods ... with

added minerals - particularly calcium and phosphorous ... is used to

complement the roughage ration.

Adequate supplies of protein ... and "energy" : carbohydrates, starches,

cellulose and fats ... must be supplied when a farmer expects calves

and milk production from a dairy cow.

If fed only hay, a 1/2 ton cow would

eat about 20 to 30 pounds daily ... a compressed hay bale roughly the

size of a big filing cabinet drawer.

... or ...

With pasture grasses at 70-85% moisture, cows will eat 100 to 200

pounds of pasture per day ... and they won't drink as much ... well,

unless it's hot.

Quick reference card for you wallet

Daily food calculator for one milk cow

A large filing cabinet drawer full of compressed hay ...

and up to 400 pop cans worth of water.

OR

Green field grasses weighing as much as a big human ...

with less water.

PLUS ... at least a couple of pails of special grain concentrate (cow chow).

Examples of Quebec dairy farm feeding practices from the early 1900s

- An interesting variety of historical feeding regimens follow. I

don't know if feeding practices still vary this much from farm to farm ... probably.

- Back then "soiling crops" were often provided in late summer to maintain

the milk tidal wave which started when the cows started on the new

pasture in late spring. These feed crops were either cut daily in the

field and brought to the cows ... or more often were cut and

put in a "summer silo" to preserve them for later warm weather feeding

as the quality of the pastures decreased.

- Today with Canadian

supply management quotas to avoid gluts and scarcities of dairy

products ... and artificial breeding which allows a farmer to better

time calf delivery and its heavy milk flow to winter (for example) ...

there is much less seasonal fluctuation of milk supply. Refrigeration

was also not available in the early 1900s. So milk flows along

different algorithms today. But getting back to a century ago ...

- Usually the first line shown for each herd feeding record below is the summer regimen, the second line summarizes the winter feeding.

- Various

by-products of food, beverage and other industrial

production are fed. In this era before paved roads and heavy transport

trucks, proximity to the factory producing the food by-products, and

related transportation costs, often helped decide the

farmer's choice of these feed sources.

(I have looked up the farm position by today's roads relative to the nearest urban centre)

... if you find it interesting to observe who was feeding industrial byproducts.

F. E. C., St. Lambert, Quebec. (Montreal : south shore)

Cows at pasture get 2 bushels brewers' grains and, in late summer, green feed in addition.

In winter, ensilage, hay, brewers' grains, gluten, and cottonseed meal comprise the ration.

J. 0. P., West Brome, Quebec. (110 km SE of Montreal)

Feeds a little grain (oats, middlings, bran, corn meal, shorts and

schumacker) when pastures begin to fail. From middle of July, green

feed, peas, oats and barley and, later, green corn are supplied.

The winter ration is made up of 30 lbs. ensilage, roots, clover hay, ground oats and corn meal or bran and meal.

Institut Agricole, Oka, Quebec. (50 km W of Montreal)

No grain is fed while cows are at pasture, but when grass fails, green oats, peas, vetches, alfalfa and rape are supplied.

The winter feed is: 25 lbs. ensilage, 20 lbs. mangels, 12 lbs. alfalfa, 3 lbs. bran, 2 lbs. oats, 2 lbs. barley, 1 lb. oil meal.

N. L., St. Paul l'Ermite, Quebec. (32 km N of Montreal)

Cows get only pasture until August when corn and other green feed is supplied.

In winter, 8 lbs. each of hay and straw, 10 lbs. of mixture of barley,

oats and buckwheat with a little bran and dust made into a mash make up

the ration.

0. S., North Sutton, Quebec. (115 km E of Montreal)

Cows are put to pasture about end of May. No grain fed, but in the late

part of the summer, soiling crops (vetches, millets and corn) are

supplied.

Winter: 30 lbs. turnips, 4 lbs. shorts, 3 lbs. corn meal and as much

corn fodder and mixed hay as they will eat make up the winter feed.

T. T., St. Prosper, Quebec. (50 km NE of Trois Rivieres)

Cows get pasture alone until August when they get oats and vetches. In

September they are allowed the run of the meadow aftermath. Turnip tops

are fed in October.

Clover hay and hot mash containing 1 lb. bran, 1/2 lb. oil cake and 30 lbs. turnips make up the winter feed.

J. J. T., White's Station, Quebec. (likely 95 km SE of Montreal ... or maybe near St Eustache, your choice)

If pasture is good, no grain is fed. Ensilage with a sprinkling of ground barley and oats when grass gets scarce.

The winter ration is 50 lbs. ensilage, alfalfa or clover hay all they

will eat; meal (barley and oats, gluten meal, cottonseed meal and bran).

F. V. B., Beaupre, Quebec. (37 km NE of Quebec City)

Feeds 2 lbs. oil cake, clover, oats and peas or corn all summer besides allowing cows to run on pasture.

In winter feeds 8 lbs. oat meal, 25 lbs. mangels or swedes, 9 lbs. hay, 3 lbs. oil cake and straw all they will eat.

Typical crop rotation on a 100 acre Canadian dairy farm in the early 1900s

(assuming some land is used for buildings, including those housing chickens and pigs)

Crop rotation serves two purposes :

- Dead plant residues from previous crops are plowed under. Microbes and insects which thrive on the dead tissue may also attack the living plant tissue of a subsequent year's crop of the same species. Crop rotation prevents a build-up of dead tissue infested with particular crop parasites.

- Crops such as grains, and particularly corn, demand significant amounts of plant nutrients (nitrogen ; phosphorous ; potassium ... i.e. potash) which are then removed from the field as

grain, corn silage, grain corn. Through nitrogen dissolved in

falling rain, roots and plant debris which rot over time, and

particularly

from nitrogen fixing legumes such as peas and clovers ... the soil has time to replace nutrients to yield good grain and corn crops in later years.

Other details to consider :

- Pasture land is naturally fertilized to some extent through cow urine ammonia and Cowpies.

- Corn fields in particular require significant manuring by the farmer in the months before the crop is sown.

- Summer fallow (leaving an idle plowed field) was not a viable option in eastern Canada because plentiful rain causes the land to become infested with weeds.

- In addition, with heavy rains on bare soil ... significant amounts of soil nitrogen can washed away through subsoil drainage.

- "The year of volunteer clover" generally follows a previous year of seeding.

Today chemical fertilizers and pesticides are widely used for weed control, parasite control, and nutrient supply.

The traditional crop rotation practice probably provides a "deeper"

reserve of nutrients

and better overall soil health when compared to

many modern chemical practices.

11 acres:

1912 corn - manured

1913 grain

1914 hay - chiefly clover

1915 hay or pasture

1916 corn

| 11 acres:

1912 grain,

plus :

10 pounds per acre clover

10 pounds per acre timothy

1913 hay - chiefly clover

1914 hay or pasture

1915 corn - manured

1916 grain

| 11 acres:

1912 hay - chiefly clover

1913 hay or pasture

1914 corn - manured

1915 grain

1916 hay - chiefly clover

| 11 acres:

1912 hay or pasture

1913 corn - manured

1914 grain

1915 hay - chiefly clover

1916 hay or pasture

|

15 acres rough land - pasture

(this might be suitable for underage heifers or perhaps dry cows)

|

3 FIELDS on a THREE YEAR ROTATION

5 acres

1912 corn - manured

1913 peas and oats

1914 clover and alfalfa; pasture in fall

1915 corn

1916 peas and oats |

5 acres

1912 peas and oats

1913 clover and alfalfa pasture

1914 corn - manured

1915 peas and oats

1916 clover and alfalfa |

5 acres

1912 clover and alfalfa pasture

1913 corn - manured

1914 peas and oats, seed clover and alfalfa

1915 clover and alfalfa

1916 corn |

Just hay ...

timothy hay flower

timothy hay flower

If you lie on your left side in a hayfield, this is how mature Timothy will appear.

Tragically, some of the developing seeds are infected with ergot fungus (the black protrusions).

common vetch

common vetch

Here is some Common Vetch a cultivated cousin of which can be sown for hay.

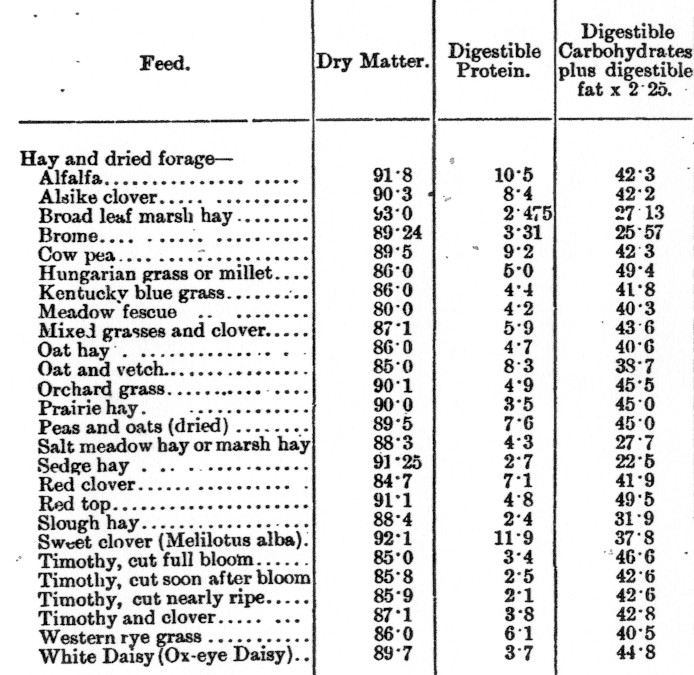

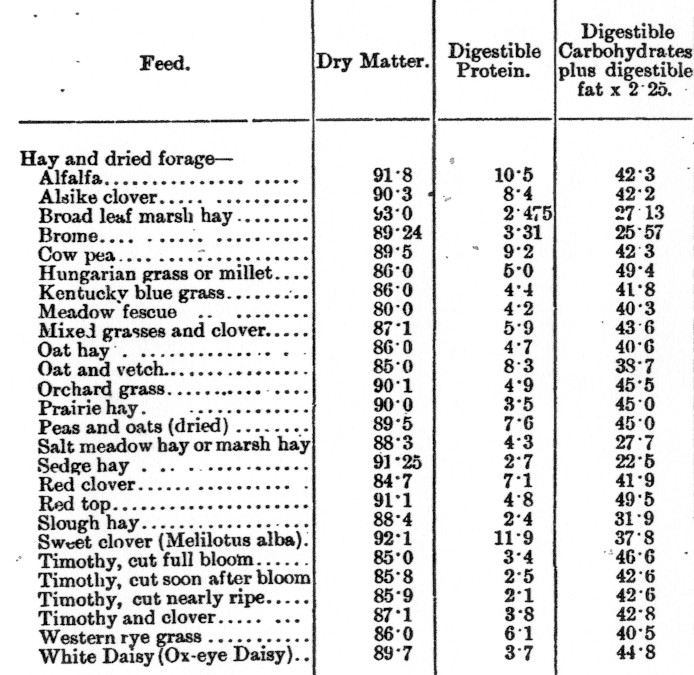

Typical Canadian forage crops (mainly hay grasses) from the early 1900s

First, note how many different

types of "hay" you might be able to use or grow, depending on your

local climate, soil, sub-surface drainage, etc. ...

This is before one considers all the other feeds:

grains, silage, root crops, industrial byproducts, etc. which would be

needed to ensure balanced nutrition for optimal milk production.

I believe dry matter is a nice

term for woody plant material ... cellulose. In the next columns you

have protein and then "energy".

You can see which hays are higher in protein and which provide more energy.

As you look at the values for the harvesting of timothy at different

stages (full bloom = flower ... ripe = viable seeds), you can see how more mature hays lose protein and energy and

become more "woody".

... So June hay is likely to be better than August hay.

chart showing dry matter protein energy for classic hays (early 1900s)

Don't worry about the units - this chart just illustrates the relative values for each plant.

In real life, the values from this chart were ready to plug into balanced ration calculation equations.

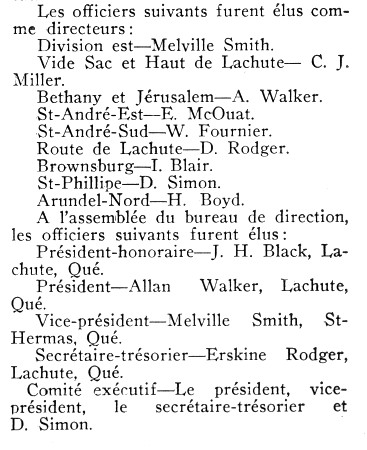

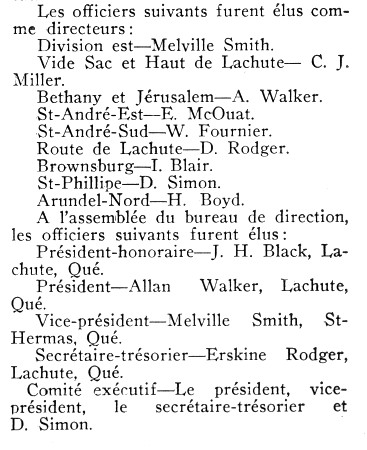

Dairy cattle breeders in 1938

The following clipping is from a French language account from the bilingual Canadian Ayrshire Review of January 1938. To read all the articles in the magazine, you had to understand both languages.

It records the 17th Annual General Meeting of the Laurentian Ayrshire

Club at Lachute, Quebec. Participants travelled through a raging

blizzard to attend the meeting at the Hotel Desjardins in Lachute.

After singing God Save the King, the group sang several popular songs and finished with O Canada.

The Secretary of the Association reviewed the year's accomplishments

including Ayrshire breeder cattle showings at the Royal Winter Fair in

Toronto.

In particular, the Secretary congratulated Jack Black for importing the champion producer Ardgowan Valda

from Scotland to Canada. A distant relative of mine who lived near Lachute, Jack Black was an

international cattleman who wouldn't take "no" for an answer when he

wanted a particular animal.

My cousin may remind me of others when he

sees this ... but for the moment I'd say four of the office-holders listed below

are relatives.

One of these was my "first boss" when I worked on his

farm 35 years later.

Laurentian Ayrshire Club officers board 1938

Laurentian Ayrshire Club officers board 1938

These purebred cattle associations were

important in Canadian agriculture as they helped develop agriculture

from a subsistence occupation engaged in by the early settlers, into an increasingly science-based

endeavour. Another Ayrshire Review

from later in the year has an article about a successful artificial

insemination project in Denmark - just a year before World War 2.

Selective breeding ; more efficient physical plant with automation ;

improved dairy sanitation ; and improved soil, crop and nutritional

science ... were in part disseminated through the meetings and

publications of these national breed associations.

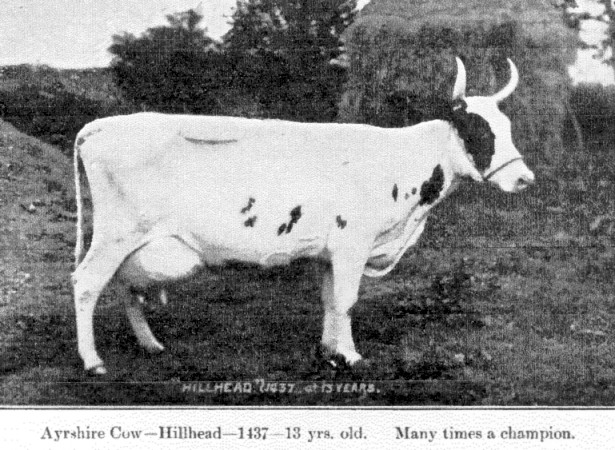

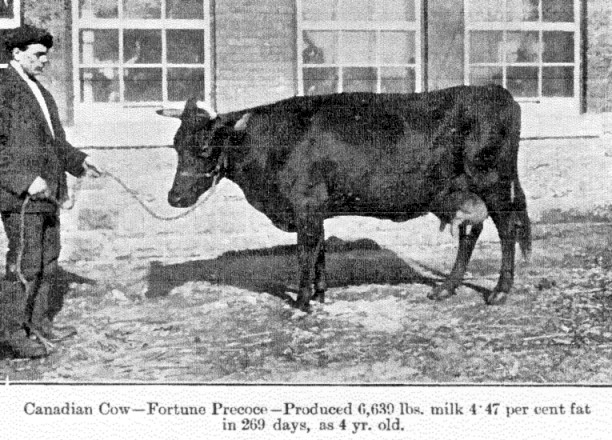

Selected dairy breeds ... from a Federal publication in 1913

The most common dairy breed in North

America is the familiar black and white Holstein. The following photos

and accounts from a 1913 Canadian Government book on Dairy Farming shed

historical light on a couple of Canada's enduring breeds of tradition.

Livestock photography is both an art and a

science. Contrasting the two photographs below will show you the

elements of a

livestock photograph which may fail to display an animal's best

characteristics or and even distract the viewer from the animal

entirely.

To get you started : the halter holding cattleman has been air-brushed out of the first photograph.

AYRSHIRE

Champion Ayrshire cow early 1900s

The Ayrshire is one of the principal breeds of dairy cattle in America.

They are medium-sized animals, spotted red, or brown and white. They

possess great vitality, are of a nervous disposition, and respond

readily to good feeding. They are hardy, and well suited for rough

pasture and scant herbage. They yield a fairly large flow of milk of

medium quality. A common yield is 8,000 pounds of 3 1/2 to 4 per cent

milk in 9 or 10 months. Their chief faults are a tendency to beefiness,

shown by a rather large proportion of the breed, and the very common

and rather serious defect of small teats.

As the name implies, the Ayrshire had its origin in Scotland. The

south-western portion of that country was in a very poor state as far

as agriculture was concerned at the end of the 18th century. An

historian of that period says that there were no crops whatever sown,

and all the food the cattle had was the grass in the bogs and wastes.

Under these circumstances the cattle were starved in winter,

"being scarcely able to rise in the spring". Such were the conditions

from which the hardy, useful race of Ayrshire cattle has come. It may

be inferred that only the fittest survived, and the inherent

hardiness seems

to have been but little disturbed by whatever crosses have been made.

It is supposed that these native cattle were crossed with imported

Teeswater or Durham cattle, and with Alderneys or Jerseys, though there is no historical evidence of this.

The first importations of Ayrshire cattle into Canada were made between

1820 and 1830. For some time they did not meet with much favour, but

with the formation of Breeders' Organizations,

Dairy Tests, and Advanced Registers they have taken their rightful

place, and every year sees greater numbers of them imported from

Scotland.

- - -

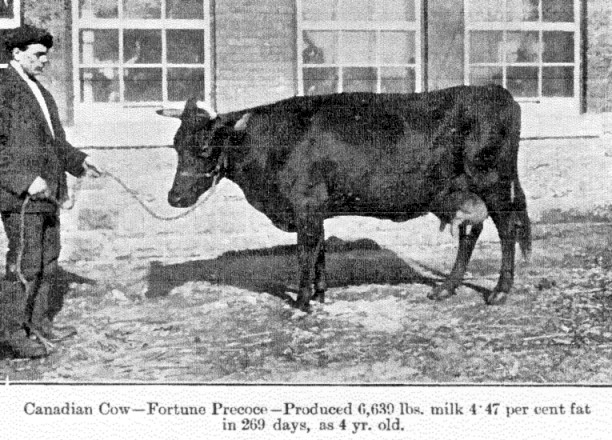

FRENCH CANADIAN

( ... in 1913. Today known as Canadien)

High producing Canadien cow early 1900s

High producing Canadien cow early 1900s

The

French Canadian cows are worthy of much consideration where a hardy

breed of rustlers is required. The individual cow is somewhat small,

weighing only 700 to 900 pounds. A bull weighs about 1,000 pounds. In

general conformation they are somewhat rough and angular; in the cows

the wedge shape is present. The colour is black, or dark-brown. As milk

producers they resemble the Jersey, though in quantity and quality they

fall somewhat behind that breed. An average of 6,500 lbs. of milk of a

little over 4 per cent butter fat is about the standard.

The first individuals of the breed are supposed to have come over from

Normandy or Brittany with the early French settlers in the17th century.

Many years of "roughing it" along with the early settlers have made

them hardy, and selection by the same people has made them productive

on light, poor rations.

A Quick Summary

before we finish off by looking at hay pictures ...

- Dairy cattle evolved eating and digesting lots of grass - but dried hay and additional water can be substituted, e.g. indoors in winter.

- When cows are

expected to produce calves and extra milk, special grain concentrates

and other feeds are needed to maintain bovine health, and to support

"consistent herd milk output" = $ farm income $.

- In the early 1900s, farms with cows could often be 'self-sufficient' ... by growing a variety of crops.

- However,

rotation of these crops was necessary to avoid depleting soil nitrogen

and other plant nutrients ... and to help control crop parasites. Extra

manure was needed for corn crops.

- Bonus: The

Ayrshire photo above is very good, but usually it is better to have the

front feet standing on a little mound of dirt, so the body's "topline"

slopes upward in a pleasing manner toward the bovine's noble head.

The Loose Hay Era

Turning loose hay with forks to speed drying circa 1900

After a field of hay was cut with scythes or a horse-drawn mowing machine

the loose hay was turned over several times during the subsequent days until it dried.

Then the hay was gathered up for loading onto wagons.

At best, if wet hay is put in a barn it will spoil.

At worst, microbial action in a confined space

will cause the hay to "heat" and burn the barn down.

Loading loose hay onto horse-drawn wagons

Compared to the roar of a tractor and the clanking of a baler,

this placing of hay on a horse-drawn wagon would seem pretty quiet today.

Horse rakes and loose hay - building a load

Horse-drawn rakes are gathering up the field of dried hay.

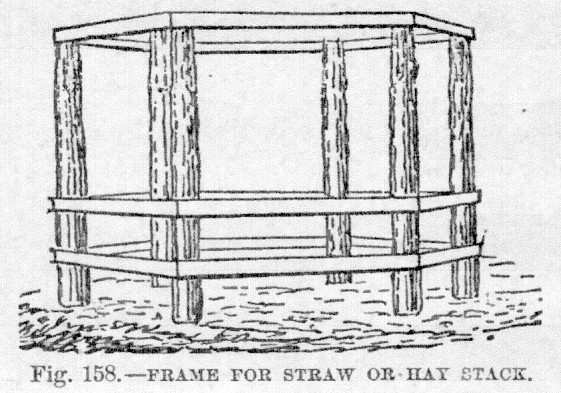

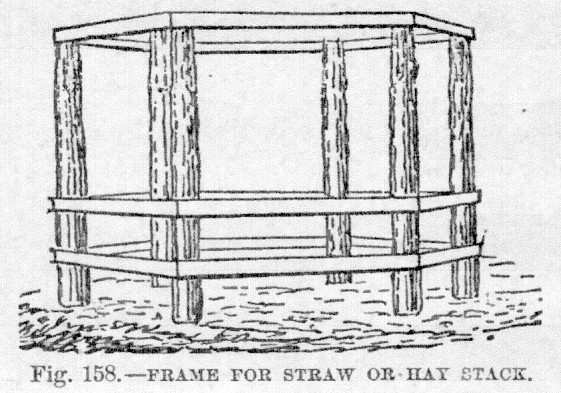

Hay stack frame for loose hay

In the Ayrshire cow photo above, you can see a nice uniform hay stack.

This is how they did it.

Large wagon load of loose hay (peaker)

Courtesy of Bob and May, here is a photograph showing a helper and two relatives :

Edward (centre) and Erskine (tractor) on Erskine's farm with a wagon load of loose hay.

Although they were more difficult to unload ...

On a particularly good hay day,

there was a tradition of making a "peaker" (load) to celebrate.

- - - - - -

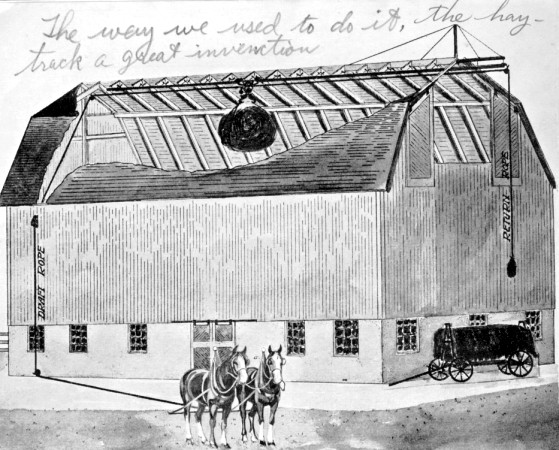

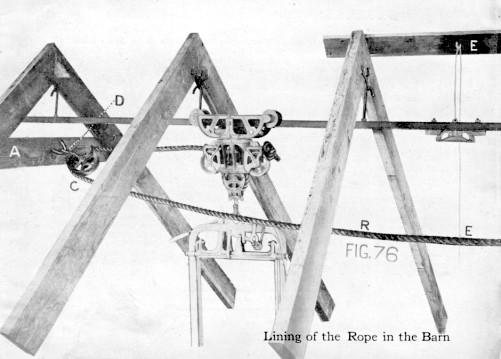

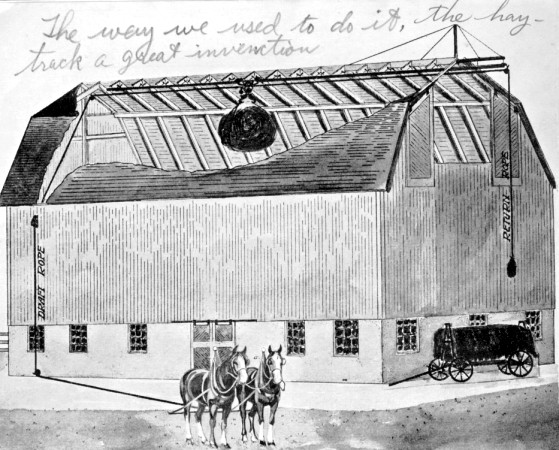

The diagram below is from an old catalog for Beatty farm equipment which I purchased.

Faced with moving Edward's and Erskine's big wagon of hay into the loft above the cows for winter feeding ...

you can understand the pencil testimonial.

Sling of loose hay being moved with hay car and horses

The horses pull the sling or fork holding the loose hay UP from wagon level ... then ALONG the monorail track.

At the desired location, a dangling rope attached to a release lever is pulled, and the loose hay falls to the loft floor.

(The hay would be gravity fed through a trap door(s) to the cows during the cold months.

The cows would be in their stalls, looking out of the windows.)

After the hay is dropped, the horses are backed up to slacken the draft rope ...

and the weighted return rope does most of the work of bringing the monorail's hay car back for another load..

Sling of loose hay being raised in barn

This view is inside a different barn layout with hay wagon access to the barn floor ...

probably provided by a ramp up from ground level (i.e. ground level = cow level).

A hay sling is being used to unload the wagon.

Like a prickly dusty layer cake, the hay slings would be placed like icing between layers of loose hay ... as the latter was loaded in the field.

When unloading, the front and rear ends of the sling would be roped upwards by the horses

until the layer of loose hay was airborne as you see it here.

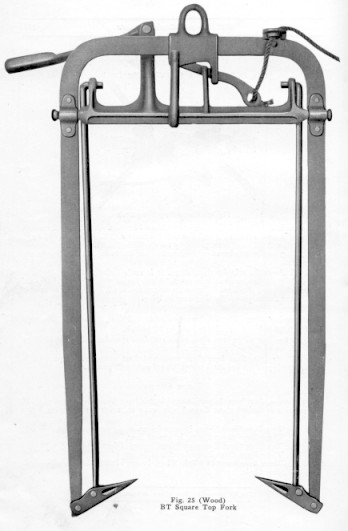

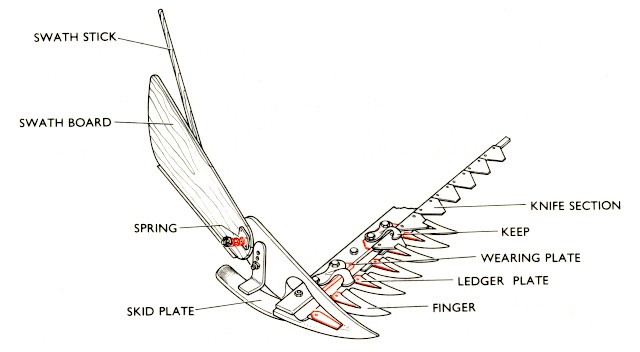

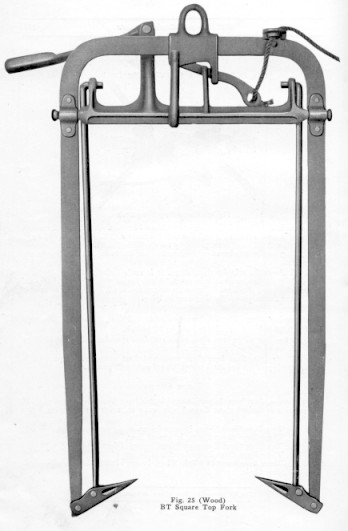

Hay fork for use from barn monorail

This was said to be the most popular fork ... used instead of fooling around with "layer cake" slings in the field.

Hanging from the monorail above the hay wagon with its pointed tips open (facing down like a fork) ...

it would be dropped from a good height, embedding itself in the load of hay, or rammed in by hand.

Once embedded in the hay ...

a lever would bring the pointed tips of the fork into the position you see,

closing

on the hay the fork had captured and compressed.

Like the sling, it would travel up, then along the monorail where the pointed tips would be released, dropping the hay.

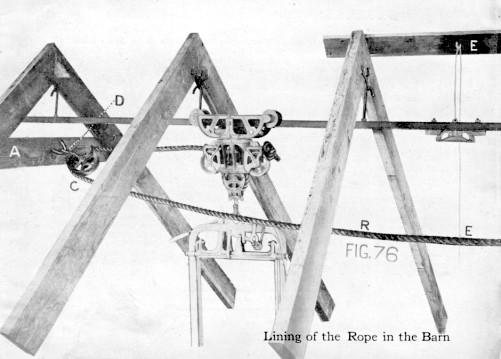

Hay car, hay fork and track along barn peak

Here are the details of the "railway" ... with the hay car on the monorail and the fork suspended below.

Many different configurations were possible, depending on the barn layout.

It was simple equipment which used horses to avoid a lot of backbreaking labour with pitch forks.

If you look closely, you can see the rope winding around three pulleys above the fork.

Slacking the rope would allow the fork to descend.

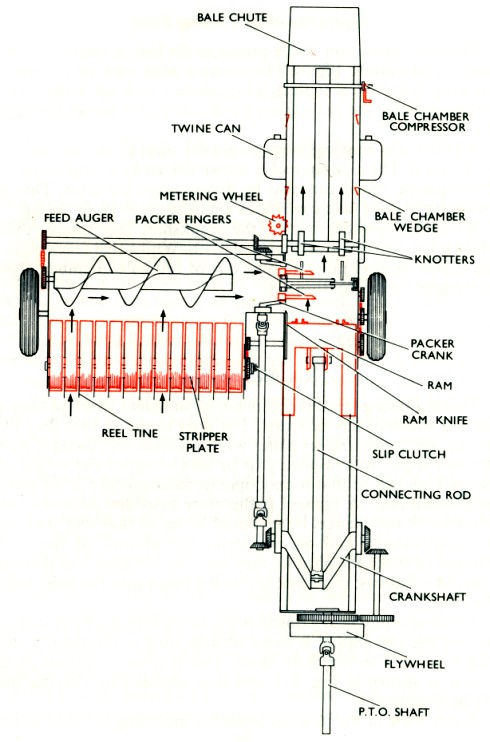

The Baled Hay Era

Fabulous hay circa 1979