Railways in War

Part 2 - German railway preparations for World War One

The Man of Peace

In the summer of 1914, an American journalist and author, Roy Norton

(1870-1942?), was travelling in Germany ... having spent a year

in that country and the previous ten years in Europe.

In the final

weeks before the beginning of the the European War... the Great War ...

World War One ... his final observations included Germany's military

preparations ... and how its citizens were incited by the government to

suddenly go to war. He made several references to Germany's

war railways during this period which appear below.

Soon French,

British - and notably for this website - Canadian railroaders sent to Europe ... would be working against this sophisticated wartime transportation system of Germany's.

Norton's article "The Man of Peace" was published in the series Oxford Pamphlets 1914-1915.

These were articles which worked to explain, justify, and promote

Britain's

involvement in the war. While this website and other accounts focus on

the Western Front in France and Belgium ... "The Only

Front is the Western Front !" ... this was a war which was being fought by the allies

and colonies of

the European great powers ... all around the world ... in Africa, South

America, Asia, and the South Pacific.

Norton's "Man of

Peace" was Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II

on whose shoulders he squarely placed blame

for the war.

The young Kaiser probably circa 1890.

A map of the various states and kingdoms which united to form Germany ... published circa 1900.

Main railway lines and rivers are shown on the map.

Initially there were numerous private railways in Germany, and some Germanic states had their own railways as well.

A Quick Survey of the German Railway System

A

British book on 'Modern Germany', published in 1905, devotes a chapter to German railway

development. It presents German Lessons for the improvement of Britain's railways ... and economy

... and legal system ... and government bureaucracy ...

Railways were a 'British invention' and the Germans imported the

technology along with the idea that private companies would usually

furnish the capital and operate the lines for a profit. Eventually in

such a system, secret tariffs evolve ... which allow railways to

charge more for captive traffic (e.g. your neighbourhood coal mine) and

less for traffic they wish to win.

Strong railways hammer weaker competitors with predatory pricing. There

is generally no 'transparency' for less significant consumers - for example, small shippers or even

individual

railway passengers. Eventually, only the most shrewd and experienced passengers can

travel from Point A to Point B across multiple railway companies

without being gouged or greatly inconvenienced by the multiplicity of

private railway schedules which were never designed to mesh.

Working under Germany's Prussian King in the late 1800s, Prussian

Premier (later German Chancellor) Otto von Bismarck saw railways as

"instruments for conveying the national

traffic" and stated that their acquisition by the state for the general

good was "a matter of course". He cited the systemic problems he

observed :

- Unnecessarily high working expenses and charges, and unnecessary duplication of routes and services.

- Chaos in the various freight charges regimes.

- Movement of goods and passengers nationally was impeded as competitors tried to harm each other.

In 1876-1879 Bismarck worked to bring the railways under state

ownership and control AND to provide preferential rates for freight

shipment WITHIN Germany - to benefit German industries.

State railway ownership increased from 6,300 km in 1879 to 31,000 km by 1902.

Rolling stock on these state lines increased as follows :

|

Locomotives

|

Passenger Cars

|

Freight Cars

|

1879

|

7,152

|

10,828

|

148,491

|

1901

|

13,267

|

24,225

|

303,364

|

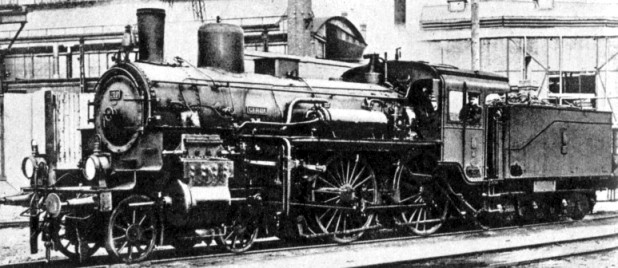

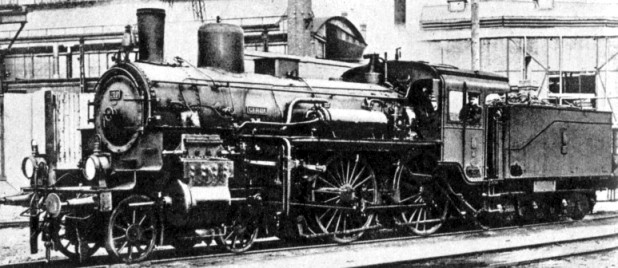

Circa 1900: A Prussian-styled locomotive for fast, medium tonnage passenger trains.

These improvements to Germany's system were noted in 1905 :

"In Great Britain, it requires years

of travel and of careful observation to learn one's way across the

country, and its numerous lines, and to avoid the many pitfalls which

are everywhere placed in the way of the inexperienced traveller. In

Germany, such pitfalls do not exist, and the greatest simpleton will

travel as cheaply, and comfortably, and as rapidly all over the country

as will the most cunning commercial traveller."

"In Germany, railway trains arrive, in nineteen times out of twenty, to

the minute, because the Government punishes severely those who are

responsible for delay."

The author wrote that a new system of freight tariffs had made a

significant contribution to the prosperity of German industries:

"The German freight tariff is of

beautiful simplicity ... every trader possesses a little book by means

of which the office-boy can calculate in a moment the exact amount of

the freight charges for any weight between two stations."

In another review of Foreign Railway Practice published in 1913, an American author noted that:

- Germany generally had the largest and most powerful locomotives

of all European systems. However, they were smaller than the contemporary [North]

American standard.

- Bridge

capacity and tunnel clearances - from earlier construction near the

dawn of railways - limited trains to about 120 axles (maximum : 30

cars with a maximum capacity of 15 tons each).

- Particular engines were assigned to specific engineer/fireman

crews - not 'pooled power'. Only larger power was double-crewed to keep

it working most of the day.

- Firemen arrived for work 2 hours before departure to start the fire and hostle their locomotive.

- Engineers went on duty 1 hour before departure and the engine crew attended to all aspects of locomotive preparation.

- At the end of their assignment, engine crews would stay on duty to attend to any adjustments necessary to their engine.

- After a run, crews were required to be off duty for 8 hours before another assignment.

- Small improvements in fuel efficiency were meticulously recorded ... and reinforced by small rewards from the railway.

- Higher efficiency fuel briquets were manufactured from Germany's

low quality brown coal ... for use when low smoke or additional

evaporative capacity were required.

- "... with the assigned engines the men act as if they were footing the fuel bills themselves ..."

The German state railway reportedly paid lower wages than North American railways.

However, this was offset by the provision of subsidized, well-kept

"living colonies" near urban railway terminals for the crews and their

families. Railway officers (managers) were given family apartments

within their own large terminal buildings - again at a significant

discount.

Elsewhere in the industrialized world, the motivation for creating company towns ran the gamut from benevolent paternalism ... to exploitive avarice

; with the employer's reward ranging from achieving their

Christian duty to their fellow humans ... to effectively enslaving

their employees ("I owe my soul to the Company Store") to satisfy their

selfish greed.

The German state railway "urban colony" perhaps fell between somewhere these two

extremes. The railway's unusual characteristic was that it was an 24 hour

essential operation, to support Germany. As the German state employees

lived on railway property, generally within a large city, their

availability for work without travel delay was assured ... very much like

Schreiber, Ontario once was.

Often people have reflected on the railway culture and its 24 hour demands on workers' lives. With the German system, perhaps it was more like a railway family lifestyle which kept all members of a railway family

in contact with other railway families as their immediate neighbours

... again, much like Schreiber, Ontario once was. It seems likely that

many railway children would follow in their parents' professional

footsteps on the German state railway.

The idea of a German railway lifestyle is probably important to the story of World War One ...

The railroaders were accustomed to living and working together ...

and behaved as if they 'owned' their equipment and 'footed the bill' for its fuel.

Failing to stay on schedule was a serious transgression in peacetime.

With a loyal, cohesive group of railroaders conditioned to follow standardized procedures ...

one can imagine that German troop and supply trains would run like clockwork.

If only such a fine system had been used ... for goodness ... and niceness ...

Military Man (of Peace)

Kaiser Wilhelm II enjoying a butt in the saddle ...

on military exercises with

Helmuth von Moltke, Chief of the German General Staff

Excerpts from

A Man of Peace

It was told me in March, of this year, by one who is

almost as great a military editor as there is in the "Fatherland", that the completion of the improved Kiel

canal was the very last act that possibly could be effected

in "preparedness".

[The

greatest value of the Kiel Canal was as a German navy shortcut between

the Baltic and North Seas. On the map above, see: Denmark, then go

south to the 'H' in Holstein for the canal location.]

" From now onward ", declared this man, " Germany

needs nothing more than the natural increase in her navy,

and maintenance of her efficiency in arms. At present we

are probably armed better than any other nation in the

world. We have adequate reasons for confidence that

this is so. Our military railways are now perfected."

It did not dawn on me at that time that usually,

when a man's preparations to do something have been

perfected, he finds a way to go ahead and do that thing

of which he has dreamed and for which he has prepared.

I did observe, however, that scattered over Germany

were more of those wonderful "switch" or "shunting"

yards, capable of entraining tens of thousands of soldiers

in a few hours yards where from ten to twenty passenger

trains could be drawn up at one time, and oddly enough,

some of these queer yards, all equipped with electric

lighting plants, are out in places where there are not

a dozen houses in sight. In some of these yards, located

at central points for rural mobilization, one saw long

trains of troop cars, dingy, empty, stodgily waiting for

use in war, if one ever came. I was told of one test

mobilization (in reply to my query as to why I had seen

so many troops pass through a small place one evening),

where twenty thousand men were assembled at ten

o'clock one morning, made a camp complete, were reviewed,

entrained, detrained, and just seven hours later

there was nothing save debris and trampled grass to show

that the place had ever been disturbed.

German sailors being mobilized.

German sailors being mobilized.

At a mere "Tank-station" [i.e. the location of a water tank to

replenish locomotive tenders with no civilian settlement] below Kriesingen, on June 12, I saw

probably

seventy-five or a hundred locomotives (I had time to count more than

seventy), most of which were of antiquated type obsolete as far as the

demands of up-to-date traffic are concerned and of a kind that would

have been "scrapped" in either England or America. Yet these were all

being cared for and "doctored up". A few engineers and stokers worked

round them, and I saw them run one down a long track and bring it back

to another, whereupon hostlers at once began drawing its fires, and the

engineer and stoker crossed over and climbed into another cab.

"What do you suppose they are doing that for ?"

I asked one of the train men with whom I had struck

up an acquaintance.

"Why," replied he with perfect frankness, "those are

war locomotives."

Reading the look of bewilderment on my face, he

added, "You see, those engines are no longer good

enough for heavy or fast traffic, so as soon as they

become obsolete we send them to the reserve. They

are all of them good enough to move troop trains, and

therefore are never destroyed. They are all frequently

fired up and tested in regular turn. Those fellows out

there do nothing else. That is their business, just keeping

those engines in order and fit for troop duty. There

are dozens of such depots over Germany."

"But how on earth could you man them in case of

war ? Where would you get the engineers for so many

extras ?"

He smiled pityingly at my ignorance.

"The head-quarters know to the ton what each one

of those can pull, how fast, where the troop cars are

that it will pull ; and every man that would ride behind

one has the number of the car he would ride in, and for

every so many men there is waiting somewhere a reserve

engineer and stoker. The best locomotives would be

the first out of the reserve, and so on down to the

ones that can barely do fifteen kilometres per hour."

Since that June day, Germany has proved how faithfully those thousands of reserve locomotives over her

domain have been nursed and cared for, and how

quickly those who were to man and ride behind them

could respond.

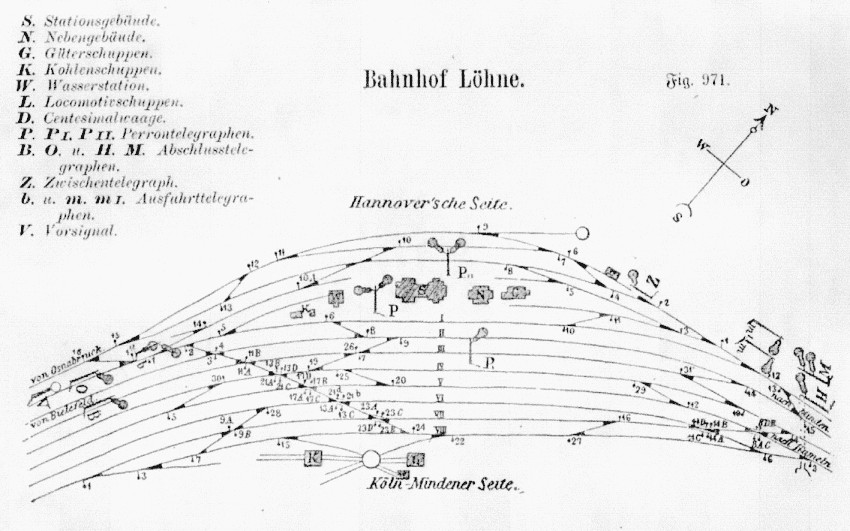

Originally from an 1885 German railway

education textbook - 15 years after the Franco-Prussian War - 29 years

before the Great War :

A railway terminal schematic diagram as part of a standardized state railway curriculum.

At this point, almost as I write, I had something

explained to me over which I have at times puzzled

for months. On February 14 of this year I was in

Cologne, and blundered, where I had no business, into

what I learned was a military-stores yard. Among

other curious things were tiny locomotives loaded on

flats which could be run off those cars by an ingenious

contrivance of metals, or, as we call them in America,

rails. Also there were other flats loaded with sections

of tracks fastened on cup ties (sleepers that can be

laid on the surface of the earth) and sections of miniature

bridges on other flats. I saw how it was possible

to lay a line of temporary railway, including bridges,

almost anywhere in an incredibly short space of time,

if one had the men. At one period of my life I was

actively interested in railway construction, but had

never before seen anything like this. Before I could

conclude my examination I discovered that I was on

verboten ground, and had to leave ; but the official

who directed me out told me that what I had seen

were construction outfits. The more I thought of

those, afterwards, the more I was puzzled by the absence

of dump cars, and that mass of smaller paraphernalia

to which I had been accustomed in all the contracting

work I had ever seen. Yet I had to remember with

admiration the ingenuity of the outfit, and think of

how quickly it could all be laid, transferred, re-shipped,

or stored. Here before me, in a letter received from

Holland but yesterday, which comes from a Hollander

who was a refugee in Germany, and on August 30 [1914 - after the war had begun]

reached home after trying experiences, is the following

:

Never, I believe, did a country so thoroughly get

ready for war. I saw the oddest spectacle, the building

of a railway behind a battle-field. They had diminutive

little engines and rails in sections, so they could be

bolted together, and even bridges that could be put

across ravines in a twinkling. Flat cars that could

be carried by hand and dropped on the rails, great

strings of them. Up to the nearest point of battle

came, on the regular railway, this small one. At the

point where we were, it came up against the soldiers.

It seemed to me that hundreds of men had been trained

for this task, for in but a few minutes that small portable

train was buzzing backward and forward on its

own small portable rails, distributing food and supplies.

It was great work, I can tell you. I've an idea that

in time of battle it would be possible for those sturdy

little trains to shift troops to critical or endangered

points at the rate of perhaps twenty miles an hour,

keep ammunition, batteries, &c., moving at the same

rate and, of course, be of inestimable use in clearing

off the wounded. A portable railway for a battle-field

struck me as coming about as close to making war

by machinery as anything I have ever heard of. I did

not have a chance, however, to see it working under

fire, for, being practically a prisoner, I was hurried

onward and away from the scene.

I know of nothing more than this, coming from one

whom I know to be truthful, that so adequately shows

how even ingenious details had been worked out for

military perfection. We shall doubtless hear, after this

war is over, how well those field trains performed their

work when it came to shifting troops in times of fierce

pressure on a threatened point, and how it added to

German efficacy.

The reader will perhaps ask by this time, "What has all this to do with

responsibility for the war ?" I answer, "When the reader was a boy and

by various efforts and privations saved money enough to buy a box of

tools, did he lock them up in the garret, or bury them in the cellar ?

When he possessed a fine bright Billy Barlow pocket-knife, did he

whittle with it ?" However, this is not an argumentative thesis, and a

good witness confines himself to what he personally considers relative,

and to personal events that may or may not be regarded as significant.

I hold no brief one way or the other.

A narrow gauge German battlefield railway early in the war.

A narrow gauge German battlefield railway early in the war.

As Part 3 will show, both sides made use of light railway systems in the battlefields.

[After observing German shore battery and naval exercises,

and having been warned by a

friend in late July 1914 to leave Germany immediately via Switzerland,

Norton

make the following observation]

It is needless to say that I was in Berlin and packing on

the following day, that immediately after I did go to

Switzerland, and that still there was no open declaration

of war on Germany's part. I stopped at Basle for a

while, interested in that fine frontier station, and one

day was amused by the extremely expressive swearing

of a man who I found out was a "switchman" in the

yards. He was complaining of over-work.

"One might have an idea", he growled, "that Germany

was going to war, from the way the German railways are

ordering all their empty trucks returned from everywhere.

Nothing but empties going home, and if anybody

makes a mistake or overlooks one, there's the devil

to pay !"

I have since learned that this inflow of empty German

carriages and trucks was so observable at other frontier

stations, that two weeks before war was declared the

German yards were swamped with this excess.

Mind the Steppes

Slowly assembling from the vast expanse of the Russian Empire, the Czar's army is heading for East Prussia.

Passenger coaches have been provided for the officers, perhaps for food service as well.

Everyone else rides in the Vista-Liners.

With Russia's railways being of a 5 foot gauge (to impede invasion by

rail) it will be necessary to march west from the border ...

unless the Germans have thoughtfully left some 4 foot 8 1/2 inch

'standard gauge' equipment sitting around for their convenience.

Technically, Germany declared war on Russia just before it declared war on Russia's ally France.

Practically, it needed the Schlieffen Plan to work in France ...

so the victorious German army could quickly ride the rails of the German state railway east to stop the Russians.

Back to sitemap