The Newfoundland Railway

... and some basic information about Newfoundland

In history, Newfoundlanders often proudly referred to Newfoundland

as "Britain's Oldest Colony".

When I volunteered with newcomers to Canada, I explained

that many native Newfoundlanders were "not born in Canada" ...

if they were born before 1949 - the year Newfoundland

joined Canadian Confederation.

While this may seem like a stupid head game ...

many older Newfoundlanders see many aspects of Canadian culture

as "foreign" and theirs as distinct and different.

Like Quebec, the social traditions, politics, music and spoken

language of Newfoundland - generally its culture - were and are unlike

those of any other place in Canada.

Many people from Newfoundland and Quebec really

feel it when they are "home" after an absence.

Newfoundland also had a railway which was unique in Canada.

We saw a little of it during its last months of operation while

on a vacation trip in 1988.

Location, Location, Location

Because of its importance to :

- Fishing - since 1500

- Regular sea transportation - in war and peace since 1500

- Trans-Atlantic telegraph cables - Heart's Content 1866

- Marconi's successful wireless experiment - St. John's 1901

- The Titanic - sank 590 km SE of Newfoundland in 1912, resulting

in the establishment of the international ice patrol

- The first non-stop flight across the Atlantic - 1919, Alcock and

Brown, RAF

- Regular trans-Atlantic air transportation - in war and peace since

the 1920s at the Botwood flying boat facility

... many foreigners over the age of 50 could probably

identify Newfoundland on an unlabelled map.

It's right out there, you can't miss it.

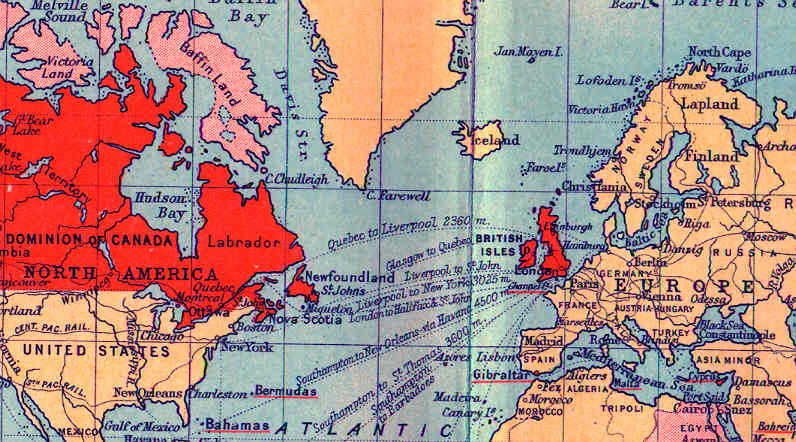

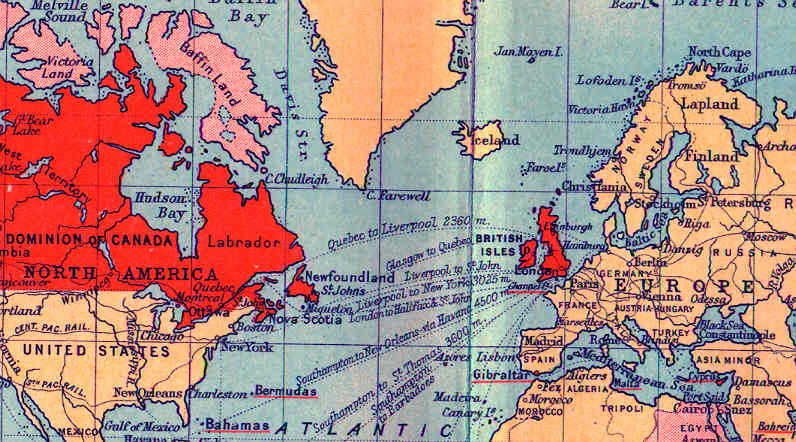

On this tiny circa 1900 map in a brittle old book (i.e.

difficult to scan well) the British Empire territory is coloured or

underlined in red.

The map projection artificially enlarges northern

areas and increases the distances between them.

Newfoundland's eastern-most point, Cape Spear, is the most

easterly part of North America :

This is about as far east as you can drive in North America

and still stay dry. The camera is facing north-west ... back to

eastern Newfoundland. Perched here on the leading tip of the continent,

we felt a great deal of responsibility for everyone else following us ... farther back in North America.

On the distant shore, shrouded in fog, you can just see

the notch in the rock - "The Narrows"- which leads to St. John's

Harbour. Atlantic convoy sailors sometimes referred to it as "Newfyjohn".

Its excellent protected harbour was crowded with navy and merchant

marine vessels during the world wars and German U-boats had a similar view

of the harbour through their periscopes from time to time.

Check out the rocks. It's not the Precambrian granite

of the Canadian Shield. The Island of Newfoundland is an extension

of the Appalachians. However, with tectonic plates coming together,

there's lots of geological variety on the island as you head west. The usual Canadian

glacial scouring, bedrock depression under ice sheets, and rebound

after the ice retreated 7000 years ago, have also contributed to the

island's features.

Newfoundland Nomenclature

- "Newfoundland and Labrador" is Canada's seventh largest province.

- Before its recent renaming, the same provincial land area was just

known as "Newfoundland".

- N&L is bigger than Canada's three Maritime Provinces put together.

- So there!

Often "Newfoundland" refers just to the island and I

only plan to work with Newfoundland the island.

Labrador

Labrador was originally a tiny seaside sliver of coastal

fishing and whaling settlements hemmed in by rock.

Other times, it was all of "northern Quebec".

One day, Newfoundland granted a logging licence on the Churchill River

in Quebec-Labrador.

Quebec had a problem with that.

So in 1902,

Canada (on behalf of Quebec) < and > Newfoundland,

as equals,

went to the British Privy Council to have the extent of

the Labrador boundary defined.

[ ... long musical intermission ... ]

In 1927 the mother country finally decided Labrador went

back from the coast ... to the height of land creating the coastal

watershed.

This is a whopping big area compared to the settled sliver

along the coast.

Canada was supposed to break the news to Quebec.

However, in the 1960s my family rented a Hydro Quebec

water heater with a big Hydro Quebec sticker on it.

On it, the map of Quebec went right through to the Atlantic

Ocean.

No Labrador.

Newfoundland Nomenclature continues ...

Vikings from nearby Iceland and Greenland were the first

"Europeans" - white guy history - known to have "discovered" and

built a settlement in North America. This was at the northern tip

of Newfoundland.

In other words, forget about Columbus being "first" if those

things matter to you.

The Vikings only stayed for perhaps three decades some

time between 990 and 1050 CE - just long enough to qualify

for full benefits under the Canada Pension Plan - and then left for

good.

Larger than Newfoundland in area, and located to its

southeast are the Grand Banks. Over a quarter million square kilometres

of the Ocean are around 100-200 metres deep here. Churning schools of

fish, the most famous being cod, were claimed to have slowed John

Cabot's ship as it sailed through the area to "discover" Newfoundland

in 1497.

Free food! Lots of people came from Europe to fish and

this adds to our nomenclature problems.

Newfoundland: England

Terre-Neuve: France

Terra Nova: Spain and Portugal

Visiting Basque fishermen could generally speak French

or Spanish because of the neighbourhood they lived in. They came from

around Europe's Bay of Biscay. Years ago they fought off the Romans.

They have their own unique ancient language which is unrelated to anyone

else's. As far as I know they may have had their own choice name for the

place.

"The Rock": some members of today's Newfoundland

diaspora

Colliding air masses and sea currents

Newfoundland is often the place where cold air from the

north meets warm moist air from the south. In part, these air masses

are part of giant atmospheric circulation cells. In part, they form over

massive ocean currents.

So Newfoundland gets lots of rain and fog. It also gets big

Atlantic storms - in winter these can feature heavy snowfalls.

On vacation, we were feeling discouraged about being unable

to see much of a famous remote cliffside seabird sanctuary in the dense fog.

With hope, we asked the Parks Canada personnel if the weather ever

changed suddenly ...

They smiled sympathetically : "Yes, it gets foggy."

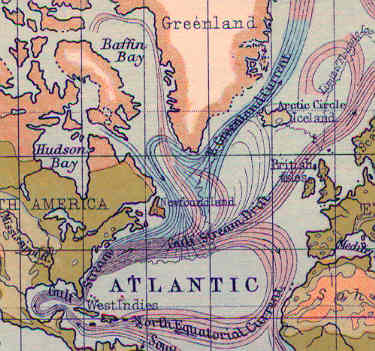

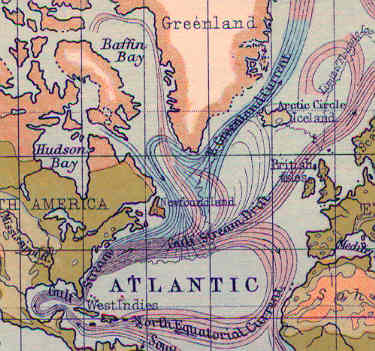

Here are the ocean currents as they were known around 1900.

You may be anticipating that I will explain why Newfoundland in

general, and the Grand Banks in particular, were such a great areas

for fish harvesting for 500 years :

- Does it have something to do with the cool nutrient-rich

water of the Greenland Current sometimes mixing with the warm flows from

the Gulf Stream over the Grand Banks, supporting plankton growth?

- Does the abundant plankton then nourish the smaller fish the

cod prefer to dine on?

- Were the numerous sheltered coves of Newfoundland excellent spawning

areas for smaller fish?

- As cod like to hang out within a few metres of the ocean floor,

and like to spawn in cool waters, were the Grand Banks the ideal place to

raise a cod family?

I don't know. Sarcastically, it seems no one knows the first

thing about cod biology.

After 500 years - including 43 years of management by "experts from

Ottawa" a (permanent, in practical terms) cod fishing moratorium

was declared in July 1992.

A Newfoundland-born Canadian Federal Minister with overall responsibility

for Canadian tidewater fisheries - supported by the best scientific advisors

- provided the following sophisticated explanation to fisherman at Bay

Bulls, Newfoundland ...

"I didn't take the fish out of the

[G*D*] water! So don't go abusing me!"

The economic and symbolic importance of the Newfoundland cod fishery

may have made it very difficult for the "win the next election" politicians

and their advisors to err on the side of caution - much sooner - when

less drastic conservation measures may have saved the resource. There's lots

of blame to spread around.

It took 500 years, but we humans finally did it.

Update 2010 ...

Recent

reflections on Marine Studies suggest some reasons for the stock's

depletion. The peak catch occurred way back around 1967 ... it wasn't

as if someone stole them all in the late 1980s. The bright new idea

back in the 1970s was to ASS/U/ME that the total cod population of the

area (x) would reproduce (y) fish. Theoretically then, if the

government gave out permits for y fish (more or less) ... this would

give the commercial fishery and the fish processing plants 'certainty'

for their business and local employment plans. Sounds reasonable and

sustainable. A real crowd pleaser. A win win situation at the end of

the day ... as the politicians say.

The old timers fishing inshore in the island's little coves had a lot

of practical experience fishing cod and although their observations

were 'anecdotal' there was wisdom in them too. They observed that the

big 'mother' cod were disappearing. It turns out that the cod which

produce the most eggs at spawning time are older females which are

physically larger. But ... on the Grand Banks the massive commercial

nets were scooping up the big fish and only the smaller fish were

escaping. Through 'natural selection' (the net holes) younger and

smaller fish were being spared and the burden for reproducing the whole

population was placed on genetically smaller fish and younger fish ...

but not the 'big mothers' which were now on our dinner tables. So the

reproduction RATE was decreasing and but no one seems to have noticed

or understood.

Furthermore, it seems that 'THE COD' are not just a single population.

Some sub-populations spend more time on the Grand Banks at particular

time of the year. Some sub-populations spend more time in local coves.

Different cod sub-populations had their 'OWN HOMES and TRAVELLING

HABITS' and these would likely be variable from year to year according

to water temperature, food, weather, you know - variables ... More

variables than just x and y.

So it turns out 'we' didn't know as much as we thought we did about the cod.

Our guesses about x (population size) and particularly y (how many you can confidently harvest every year like clockwork)

were made in political-industrial expedience ... but in horrible ignorance of true the nature of cod.

In the end, the professional knowledge and ethics of the old-time inshore cod fishermen could have helped us ...

Sometimes nature is good to you and you have a good year.

Sometimes the fish aren't there and you have a bad year.

You must co-exist with the natural creatures and environment and respect the fact there are

some mysteries of nature which are not as easy to understand as one might think.

Twenty years later, in 2010, we have a big royal commission pending on

the west coast because all our salmon are suddenly missing !!

You see, the fisherman were promised y salmon out the x quantity which

fisheries experts expected to return ... and they didn't show up !!

Well shoot !

... I wonder why THAT happened ?

but getting back to our narrative ...

The Railway on 'The Rock'

From the 1860s, here is a civil engineer's opinion about

the interior of Newfoundland - relating to how easy railway building

might be in that area :

"a dreary waste of alternating rocky hills and ridges, with widespread

barrens and marshes, intersected by innumerable foaming torrents,

which, rushing through deepest, precipitous gorges, flow tumultuously

into the many fiords and inlets which indent the southern shore"

... all right then ... I guess we'll keep the north side in

mind if we ever build a railway around here.

Newfoundland maps are almost always pushed off the right

edge of the page.

This well-worn map from the early 1920s is the best

I could find to provide a quick overview of the railway's mainline :

The poor printing quality of this 80+ year old map shows

the red line of the railway above the dots of the many settlements

it created. Some branchlines are missing, but you get the idea that

the railway went from St. John's, around the north to avoid the southern

terrain, to the point closest to the mainland at Sydney, Nova Scotia.

A ferry connection was set up between Port-aux-Basques and the Sydney

area across Cabot Strait.

Two important centres which we will visit along the railway on additional

Newfoundland pages - Corner Brook and Gander - do not appear on this map.

Here's a view of the still-active railway at Gambo in 1988.

In the

photo, flowing from right to left, the water will reach Freshwater Bay

and then Bonavista Bay on the Atlantic Ocean.

Built as economically as possible, but still creating economic crises

for Newfoundland,

the railway had to get through some difficult terrain

using the technology of the late 1800s.

Using a really cheap metaphor, the railway was a bridge:

- from the unpredictable subsistence status of a fishing colony

with many isolated outport settlements along the coast ...

- to a more diversified and more industrial economy with increasing

standards of living ...

- to a role as a key military and civil aviation crossroads, requiring

the latest technology ... and hosting a few US nuclear weapons in the

process ...

- to a point where the railway was made obsolete by the Trans-Canada

Highway in 1965 and Canadian Confederation guarantees from 1949 to maintain

the railway were eagerly exchanged for money to improve highways.

Looking at little more closely at the railway

and some of its rare features:

In misty dark Corner Brook in 1988 we are looking at

some maintenance of way equipment stored in the railway yard.

The rare orange cars are snowplows, needed to deal

with the large amounts of heavy wet snow dumped on Newfoundland during

many winters - particularly at the higher elevations.

More rare ... than snowplows on Canadian railways in

the 1980s is the wooden boxcar with plain bearings instead

of "permanently lubricated" sealed roller bearings. With a plain bearing,

carmen at each terminal must manually maintain a reservoir of oil at each

axle bearing (8 per car) which is continuously spread on the turning bearing

surface by a "lubricator" (like a fuzzy folded-up towel, wicking up the

oil from the reservoir).

- If the oil leaks away or if the lubrication is imperfect :

- The axle bearing overheats.

- The oil smokes and smells.

- The oil and lubricator pad may catch fire.

- And if the train is not soon stopped, the overheated metal

axle end may break off causing a derailment.

Before radios, a crewman inspecting a passing train would hold

his nose to signal that he had spotted a "hotbox". He might then touch

his own head or tail end to show where in the train the defect was spotted

- or he might draw his hand across his waist if it was in the middle of the

train.

The crew in the passing caboose - if they had not already smelled or

spotted the hotbox smoke from the cupola - would stop the train immediately

and determine if the bearing could be fixed by adding oil or fiddling with

the lubricator. Otherwise, the car would be closely observed as it was

pulled gingerly to a siding or backtrack for heavier repairs by carmen.

Even on the interesting Newfoundland Railway it has been some time

since this wooden boxcar was used for carrying revenue loads. Instead of

scrapping old equipment, railways often use obsolete equipment to support

track maintenance work.

Have you looked at the really rare track yet? Does

it look normal?

Even in my too-dark photo you can see that the rails look "too close

together".

Beginning with Britain, and continuing in the United States and

Canada, the distance between the inside surfaces of the railheads is "always"

4 feet 8 1/2 inches (1.435 metres). This is referred to as "standard gauge".

There were some exceptions in North America and there are many exceptions

around the world - both narrower and broader gauges.

Inspired by the War of 1812, Canadian railways were required to use

a 5 1/2 foot standard after 1851 because it was too wide to be used by

American railway equipment - to foil a military conquest. At the border,

massing US troops, guns and supplies would have to be transferred to Canadian

equipment of the correct gauge - assuming any would be left behind at the

border for their convenience.

Once American invasion seemed less likely in the 1870s, the economic

advantage of being able to ship a boxcar of apples or machinery directly

from a Canadian railway to an American railroad, or vice versa, caused

the Canadian railways to convert to standard gauge.

So why didn't Newfoundland start out with standard gauge in

the late 1800s ?

Newfoundland railways used a British "narrow gauge standard" of 3

1/2 feet. This makes the gauge about 75% of standard gauge. American narrow

gauge lines often used a 3 foot gauge. When the rails are closer together,

the equipment is physically smaller. Narrow gauge was used because :

- Newfoundland was a seafarin' society and proud of it, so even

a cheap trans-Newfoundland railway was a waste of money as

many Newfoundlanders saw it.

- The railway was used to:

- Open up the interior.

- Pull out natural resources for export.

- Replace travel by sea between Newfoundland settlements when

sea travel was not possible, convenient, or safe.

- ... so the need to interchange cars with other railways was

not a priority in the late 1800s when the first lines were laid. Exports

and imports would still travel as ship's cargo.

- The key "selling point" with narrow gauge is that it is cheaper

to build :

- The wooden ties don't have to be as long - and this adds up

on a 547 mile long mainline.

- Rock cuts, embankments and tunnels don't have to be as wide

or as tall.

- The rail can be lighter because the cars are smaller and each

car carries less.

- Bridges don't have to be built as heavily because locomotives

are smaller and lighter.

- Generally, the railway is more tolerant of being laid on the

contours of the land.

Below is a shining example of track laid on the contours of the land

:

At Gander Station the sun has set and the

shiny railheads of the mainline follow the hills and sags of the countryside.

The rails at the airport spur switch need lining and surfacing

which they will never get - they will soon be pulled up.

Trains have rolled by this location for 90 years.

Newfoundland's culture and history are unique in

Canada.

The richness of the culture may be partly attributable

to the different types of isolation

and local sense of community

experienced by many Newfoundlanders through history.

Joining Canadian Confederation in 1949 was seen by many Newfoundlanders

as a mixed blessing at best.

Located beside a rich fishery, with an excellent natural harbour

at St. John's,

and situated at the eastern extreme of North America,

Newfoundland has been a key transportation and communications crossroads

for much of its history.

Like Newfoundland and its people, the Newfoundland Railway was unique.