Rolly

Martin

1928 -

2006

Originally from

St-Modeste near Rivière-du-Loup, Rolly came to Northern Ontario

as a young man. He first worked as a sectionman on the CPR at

Aubrey (near Biscotasing), Sudbury and Cartier. During this time

he also worked briefly for the Algoma Central Railway in the

same capacity.

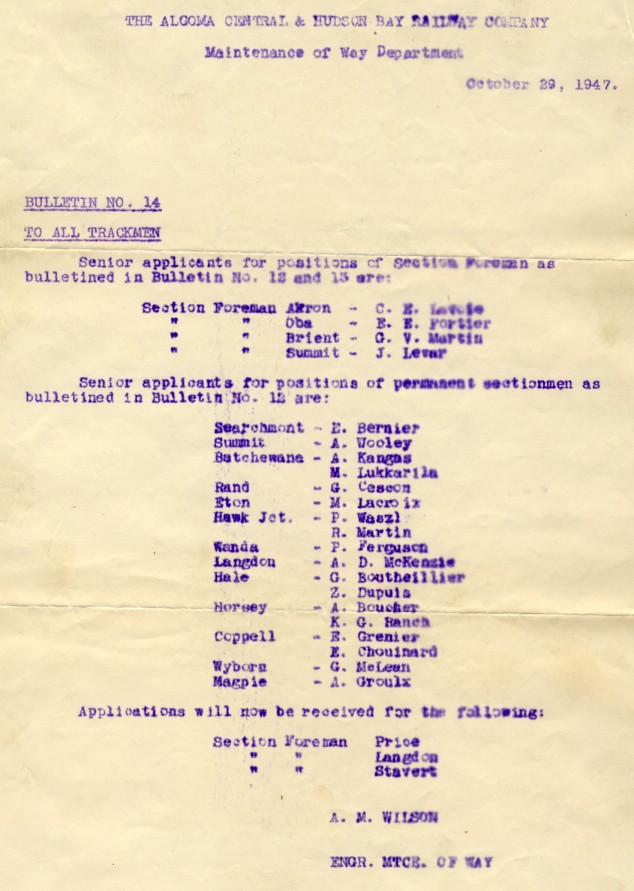

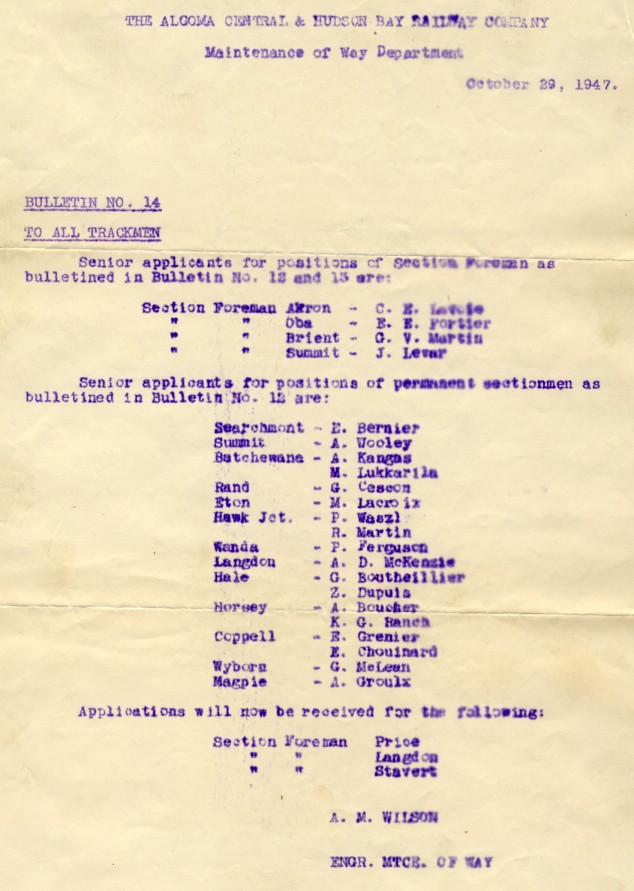

Rolly is shown on this bulletin to be the permanent sectionman

at Hawk Junction.

Rolly is shown on this bulletin to be the permanent sectionman

at Hawk Junction.

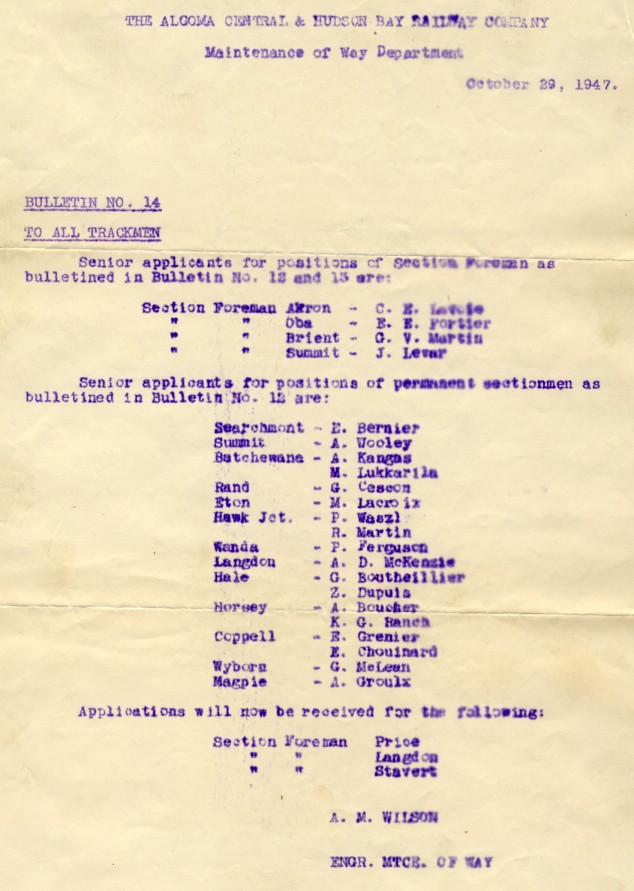

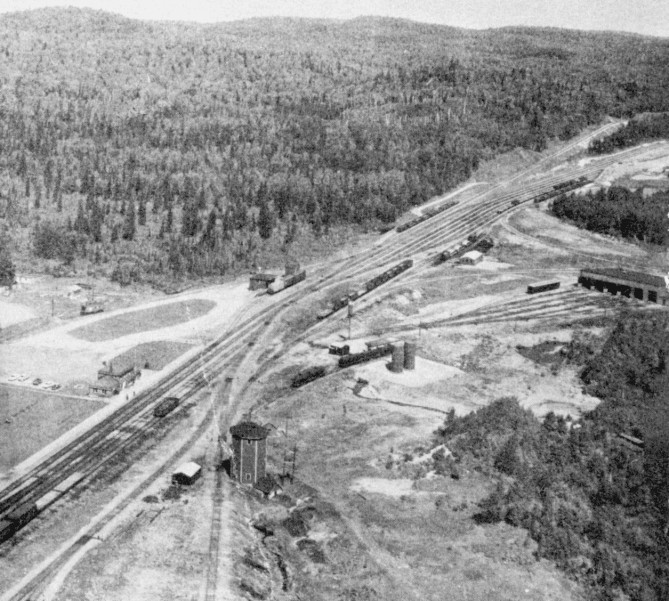

Hawk Junction - 'timetable north' is to the right.

The track at the left corner leads south to Sault Ste Marie.

The Michipicoten Subdivision to Lake Superior climbs away from

the mainline at the top right.

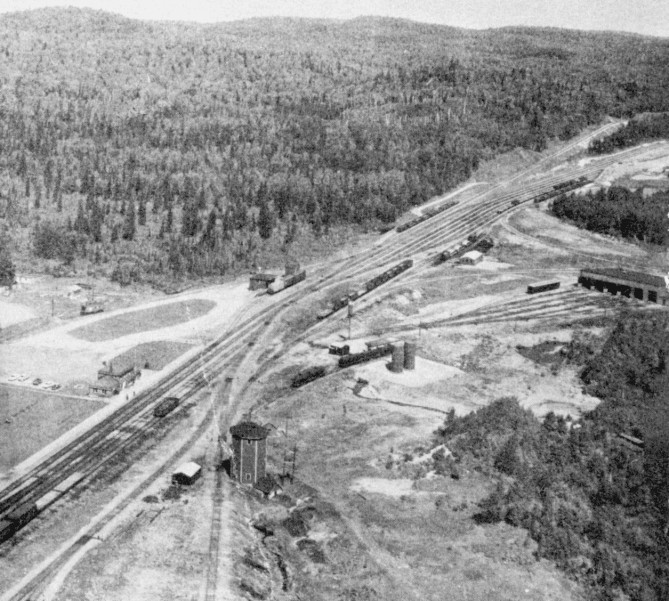

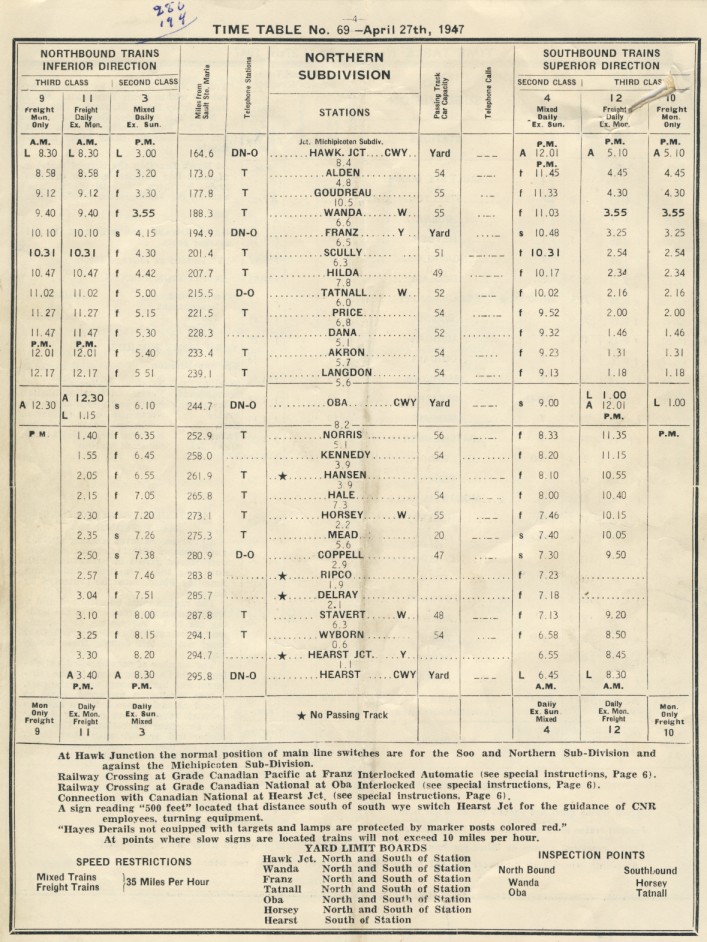

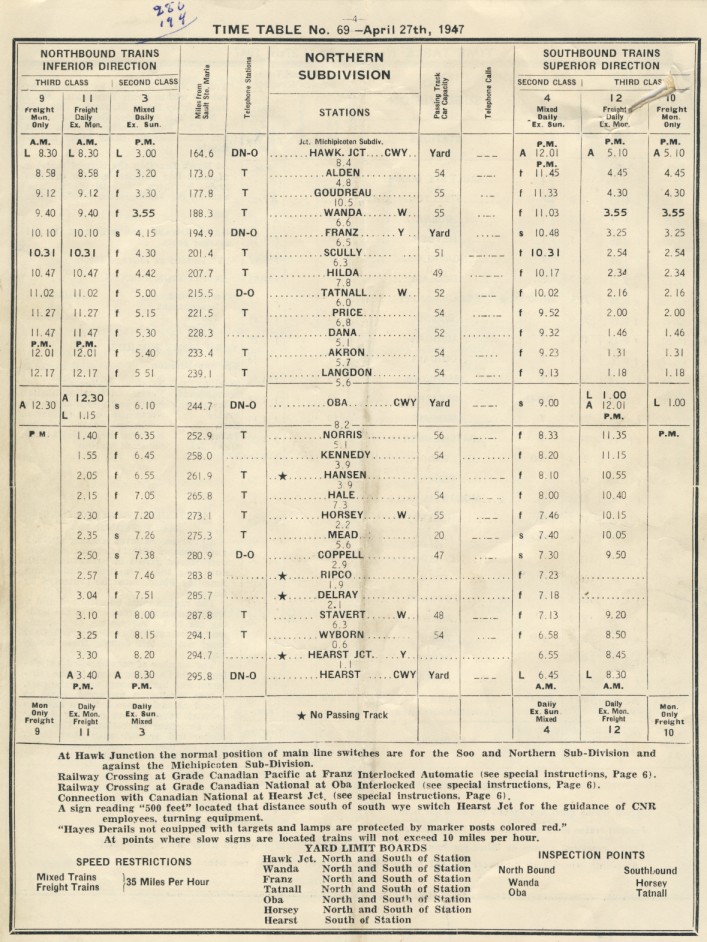

Rolly's timetable of the line north from Hawk Junction.

At

prescribed intervals - often weekly or more frequently - the

roadmaster travelled over 'his' entire track.

Any defects noted were documented, and slow orders were issued

for trains, if necessary, until repairs could be made.

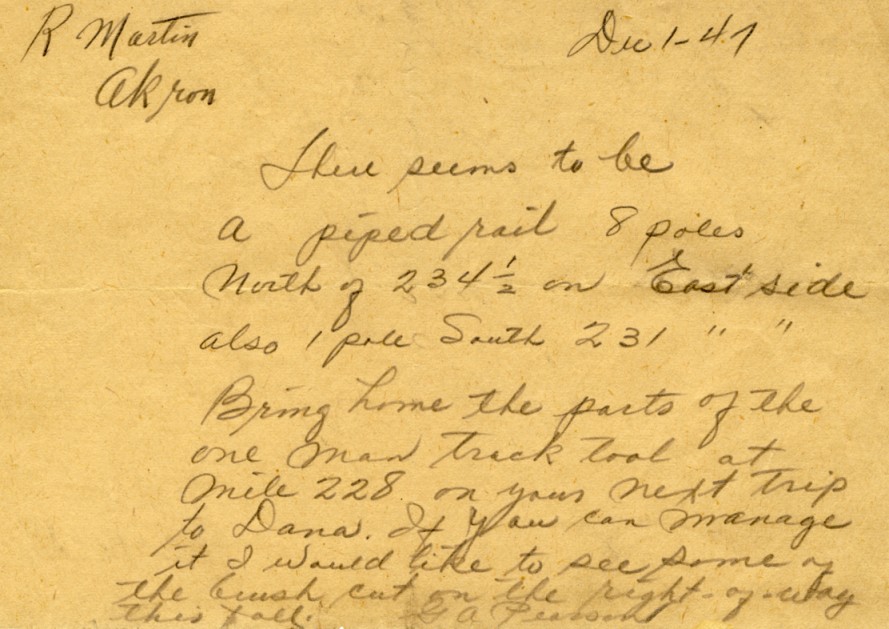

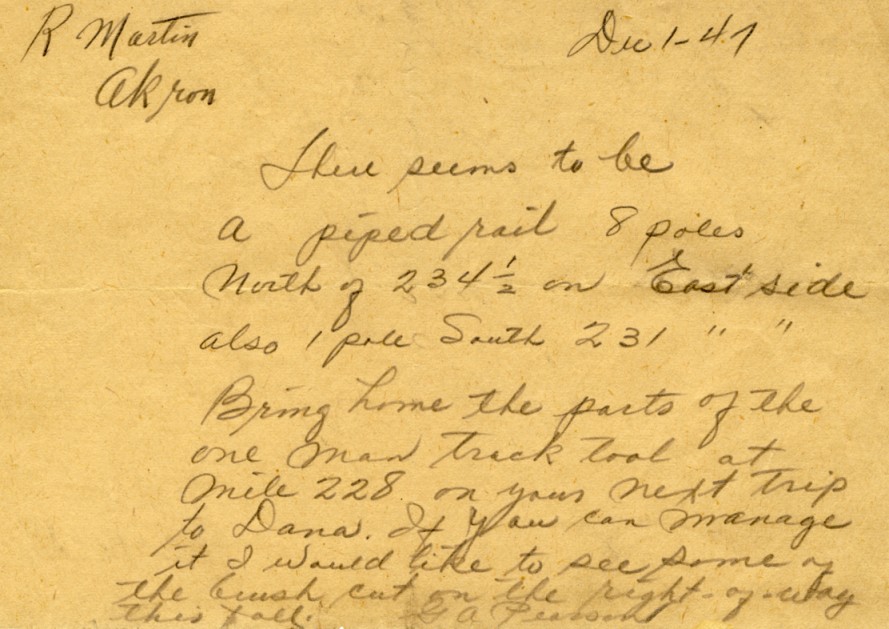

Here, Rolly has received a note to attend to two defective

rails.

The locations are given by railway mileboard, fractions of

miles, then 'telegraph poles' for greater precision.

Piped rail, the long version:

If a steel ingot cools such that a cavity or depression forms

in it ...

and this flaw is passed on to the rails which are rolled from

it

...

a lengthwise crack can form along the vertical portion of the

rail's ' I ' shape over time ...

where the molecules of the smooth ingot surface were pressed

together ...

but failed to integrate with each other into the steel

material's solid structure.

(You fold over bread dough or Silly Putty, but don't mash it

to get rid of the folded-in outside surface)

Piped rail short

version:

A piped rail has a longitudinal web fissure ... which, when

inspected, will reveal a glossy-faced internal fault.

How would you do it ?

Using an old 'pump' handcar and applied physics, Rolly changed

a rail

(probably about 800 pounds)

on the Michipicoten Sub without assistance.

Assume you will not bring the defective rail back with you.

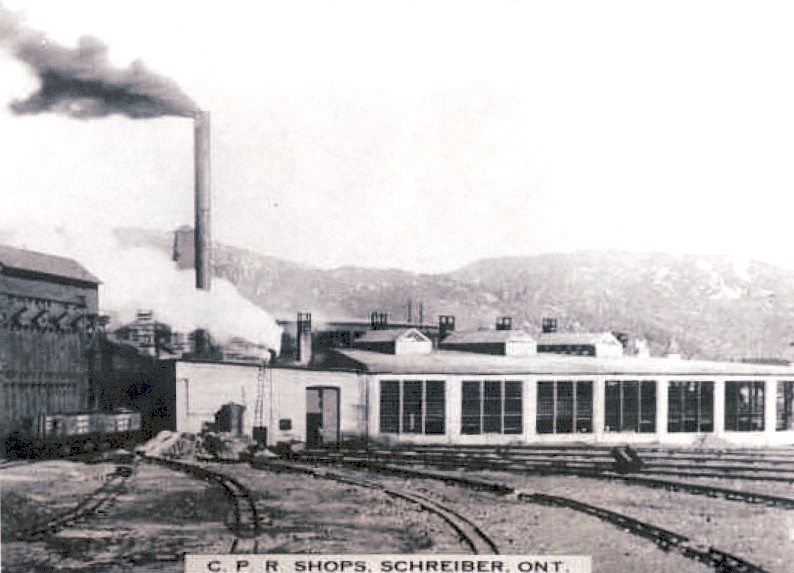

On to Schreiber

Rolly then moved to Schreiber, working as a classified

labourer

and ashpitman at the busy 22 stall roundhouse there. In these

occupations, he would gain the experience of working on

steam

locomotives.

This would include :

- Working as a locomotive 'wiper' (cleaning).

- Refilling the tender with coal and water, and

refilling the locomotive's sand dome.

- Cleaning

ash from the firebox after a locomotive came in after a run,

and

loading the waste into hopper cars for disposal - a dirty

job.

- Helping skilled staff with minor repairs requiring

brute strength, or a second, third, fourth pair of hands.

- Banking

and tending the fires of 'idling' steam locomotives as they

sat on the 'ready

track'. Draining a locomotive so it could just sit around

outside and

'freeze' was probably avoided because of all the pipes,

valves and

welded components which would not drain well and could be

damaged by ice expansion.

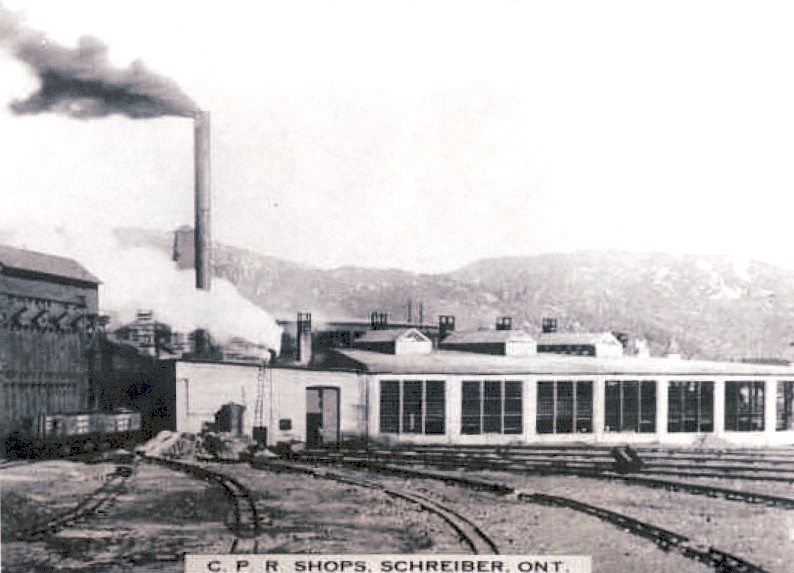

Schreiber in the late 1930s.

It seems they had an elaborate ash handling system with carts

and tracks.

There is lots of coal smoke ...

to produce the steam being used for shop power and to pipe

into the equipment, if needed.

Schreiber, including an enclosed roundhouse turntable in the

late 1930s.

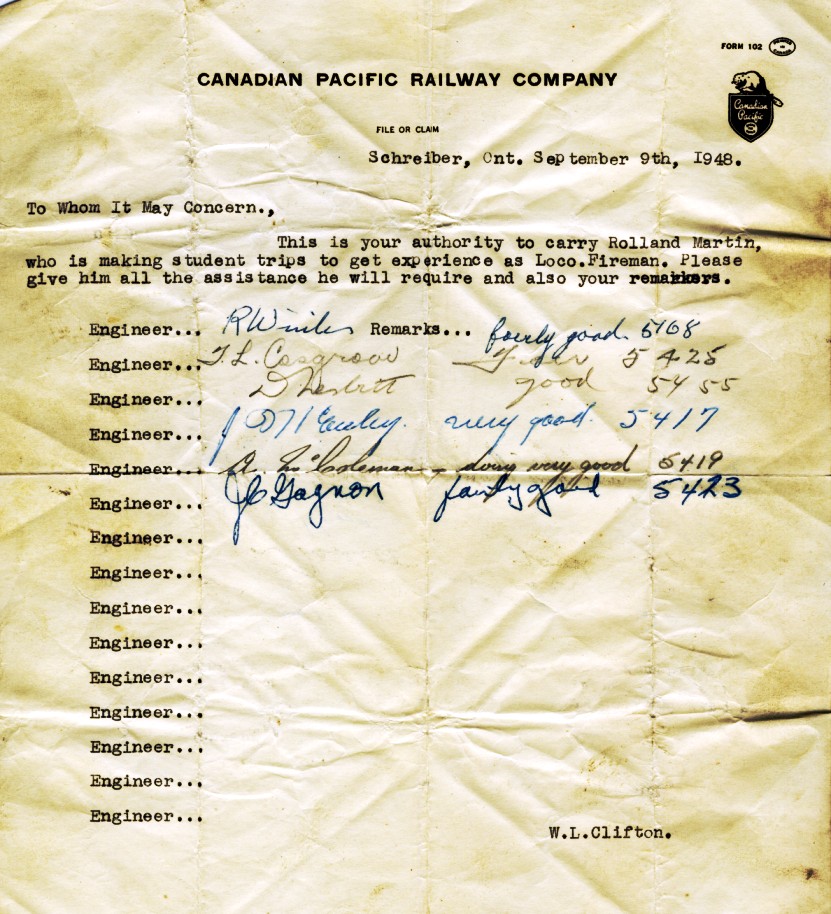

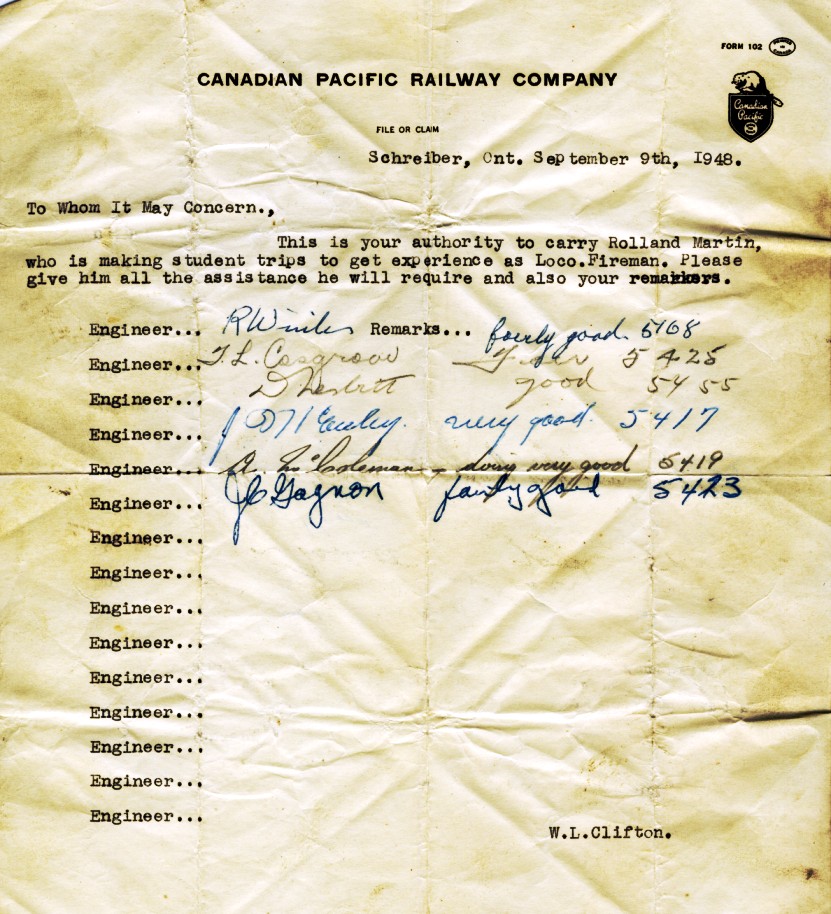

Rolly's record of unpaid fireman 'trial trips' ...

for experience in the engines as they travelled over the Heron

Bay and Nipigon Subdivisions.

(I never did meet engineer J.C. Gagnon while I was briefly

working in Schreiber)

The paid firemen would show him the work and the engineers

would grade him on attributes such as ...

Alertness and attention to signals and safety.

Knowledge of rules and locomotive procedures.

Cab neatness, e.g. keeping the deck clear of loose coal.

Physical capacity to shovel tons of coal per run, and to

refill the tender from a water tank.

Most important: Thinking

ahead ...

to always ensure enough heat and steam pressure was built up

by the time the engineer needed it.

For example, having everything very hot before climbing a long

grade.

There is a lag between throwing more coal in ...

injecting more water (even from a feedwater heater) ...

and finally getting more steam.

But if you are making too

much steam and are not using it up ...

... the safety valves would lift with a continuous thunderous

roar until the danger of a boiler explosion was relieved.

Would you throw a scoop of coal out the cab door onto the

right of way?

You are being just as wasteful when the 'pops' lift and the

steam is wasted!

To make things interesting for the student fireman ...

Different engineers often had different expectations and

different standards.

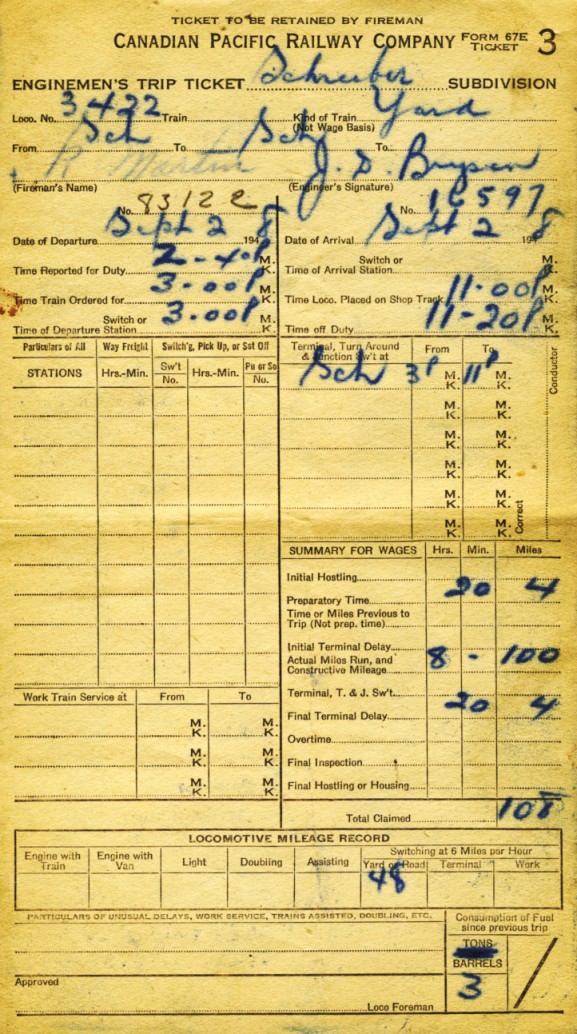

Working as a Fireman

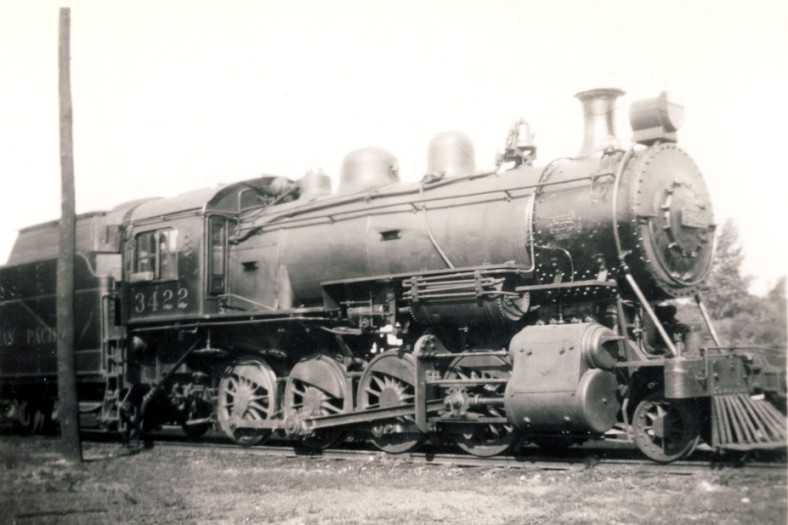

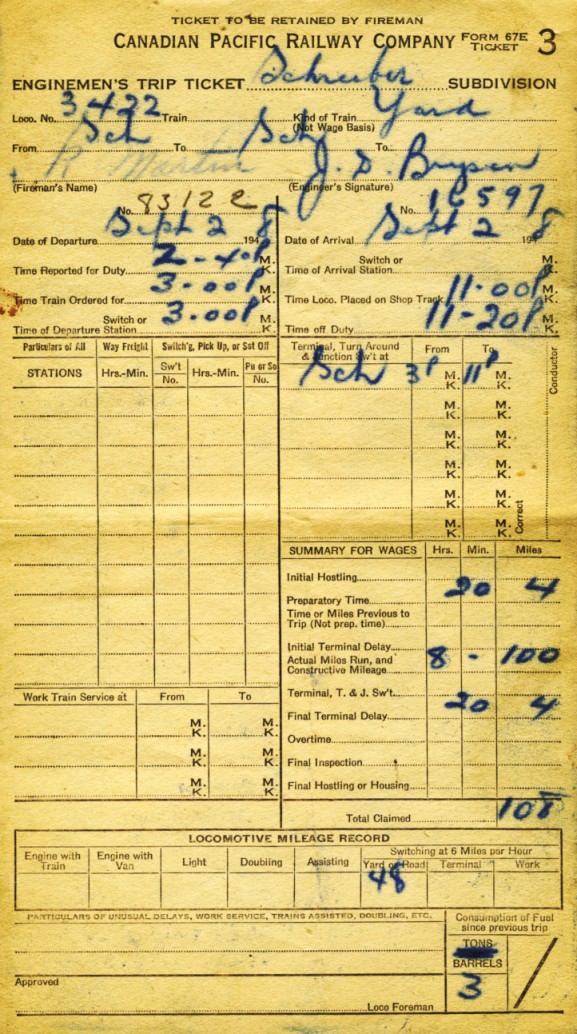

Rolly qualified as a fireman, making his first run on

Thursday, September 2, 1948 on CPR engine 3422, a 2-8-0 built by

Alco

in Schenectady in October 1904.

CPR 3422, twenty years before Rolly's first paid trip.

Shown as a freight engine

in the 1930s, before its conversion to a switcher.

Rolly reported for work at 1440hr, had his 20 minutes (= 4

miles' pay) prep time and the locomotive was on duty at 15hr.

Notice that the fireman shovels about 3 tons of coal in an 8

hour switching shift.

Engineer Bryson was at the throttle as the crew performed the

regular Schreiber yard assignment.

Back then, besides switching freight cars for various

destinations,

this work would likely also include changing conductors' vans

on freight trains ...

before the age of 'pooled run-through cabooses' which stayed

attached to the through trains.

For the standard 8 hours (100 miles' pay) they worked until

23hr.

Then, another 20 minutes paid to tidy up as the Schreiber

locomotive shop took the locomotive back,

or the next switcher shift took over the engine and its

work assignment.

The minute to mile equivalents come from the Collective

Agreement.

This

'ticket' was Rolly's receipt ... and the conductor would

submit the

paperwork for the crew's pay to the Schreiber yard office.

Upstairs within the Schreiber station, the Division staff

would prepare, and issue the payroll cheques on payday.

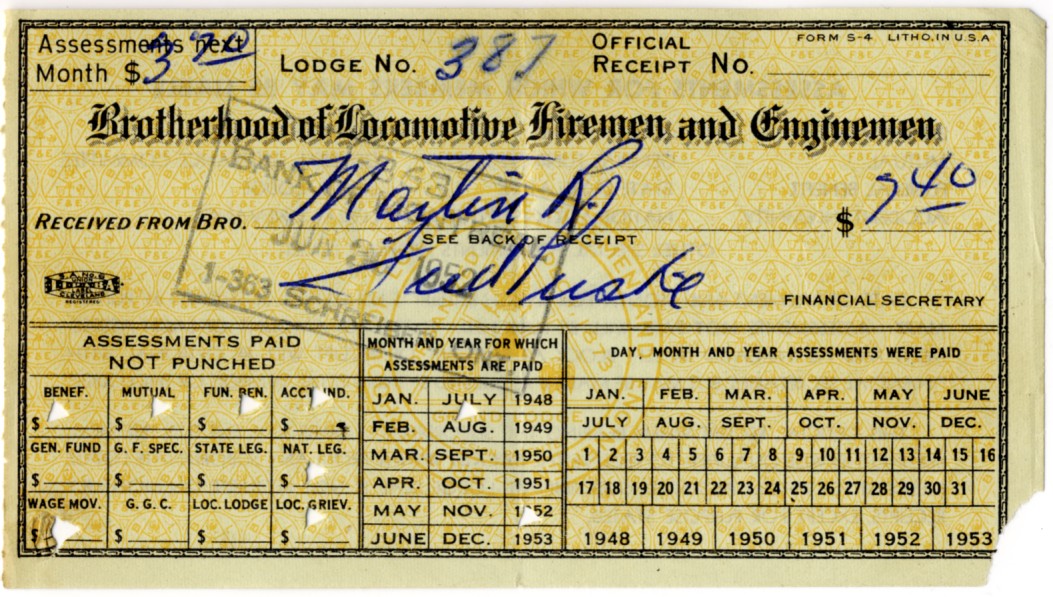

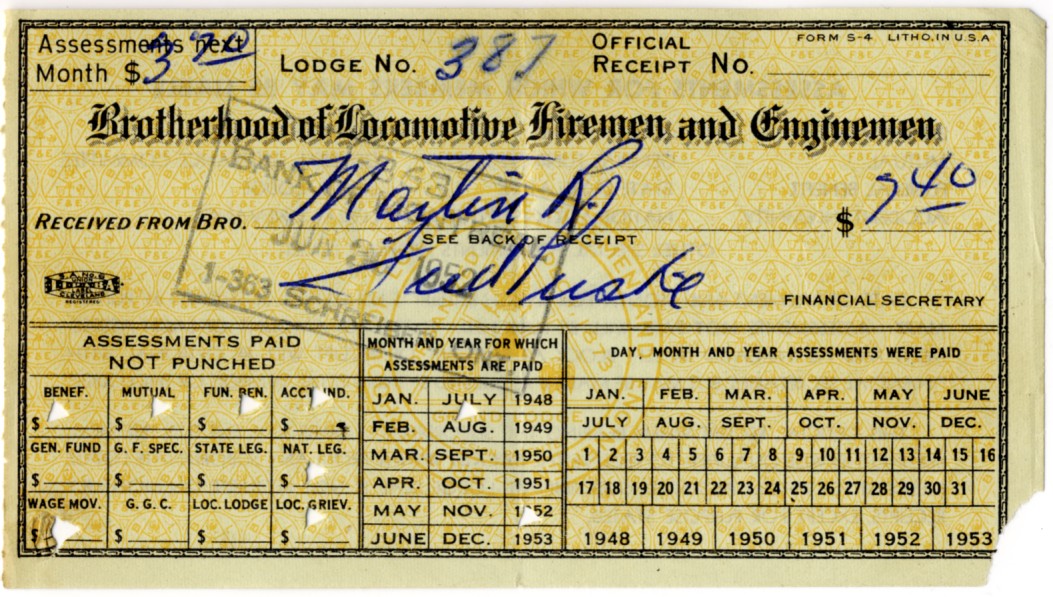

A receipt for Rolly's union dues.

It was also in 1953 that he was married, and shortly thereafter

he brought his wife Thérèse to Schreiber. While most families in

our society are usually together at the same time each day, the

families of most running trades employees experienced a much

different type of

life. They seldom knew when the telephone would ring - and their

loved

ones would once again be called to work at any hour of the day

or night.

During his career, Rolly worked on locomotives representing over

85 years of technological change. Just after beginning his

running trades career as fireman, Rolly witnessed the arrival of

the first diesels on the Schreiber Division in 1951. This was

one of the many changes Rolly was to experience over the course

of his long career.

Rolly's

eastern terminal was White River - shown here in the 1950s.

Westbound doubleheaded steam and a new diesel freight

locomotive warily eye each other in front of the terminal.

The changes Rolly experienced included ...

- Train order and timetable, to automatic block

signals, to computerized centralized traffic control

systems.

- Introduction of end to end and train to wayside

radio communication.

- Electricity replacing kerosene in lanterns and

markers.

- The end of steam and full dieselization of the

division.

- The Canadian

- trains Number 1 and Number 2.

- The introduction of computerized train consists and

train profiles.

- The reduction or elimination of firemen, section

gangs, operators and tailend trainmen.

- Roller bearings replacing plain bearings.

- Ribbon rail replacing 39 foot bolted rail sections.

- The ability to operate mile long trains and

trains of 10,000 or more tons.

- Wayside "talking" hotbox detectors.

- Company managers who were recent university

graduates replacing "up through the ranks" managers who had

experienced the realities of running trades work.

- The installation of event recorders in all

locomotives.

- The elimination of vans.

- The discontinuance of through passenger service on

the Schreiber Division after more than 103 years.

However, some things

about railroading along the rugged granite shores of Lake

Superior have not changed over the years ...

- Temperatures of minus 40 and severe blizzards.

- Rock slides with some boulders the size of

automobiles occupying the track just beyond a blind curve.

- Washouts and tracks flooded by the waters of Lake

Superior.

- Staying awake and alert after long days on duty with

only a few hours of sleep in between.

- Rails broken by the cold.

- Days so cold it is not possible to get air through a

train.

- Locomotives shutting down at the worst possible

moment.

- Sitting in a siding for hours.

- Derailments stranding crews away from home for days

at a time.

- Broken coupler knuckles and drawbars in the middle

of a cold winter night.

- Signals obscured by blizzards and thick fog.

- The

trauma of striking and killing trespassers, or motorists who

were

careless at a level crossing. Seeing the actual carnage and

talking to

police as the public gathered. Being unable to eat for

a week,

and preserving the yellowed newspaper clipping forever. (In

recent

years, railways have finally provided counselling - usually

at the next

terminal)

- The possibility, through no fault of your own, of

suddenly

seeing a train approaching on your track with a combined

closing speed

of 80mph.

- The knowledge that a moment of your own inattention

can land you in the bush, "on the carpet", in the hospital,

or worse.

Westbound freight at Jackfish Bay (Tunnel Bay) from a

postcard I recently purchased.

The trackside frame over the second unit is a 'tell-tale' ...

dangling wires to warn roof-walking crew members that a tunnel

is approaching.

Notice there are three crew members in the cab.

Former steam firemen were carried as troubleshooters for the

new diesel power.

Today many locomotive on-the-road problems are solved by

'turning the computer off and on' from the locomotive cab

'office'.

Back then there were no computers.

Water, fuel, and oil leaks could make the rocking floors of

the enginerooms slippery.

Dangerous moving parts and hot surfaces had to be avoided as

you lurched through the carbody.

Buttons, levers, valves, and switches ... manipulated in the

correct sequence,

pipe wrenches, spanners, and hammers,

knowledge, experience, and shouted orders from the hogger,

and information from a well-travelled personal library of

locomotive manuals,

were

what the fireman used to keep the train moving.

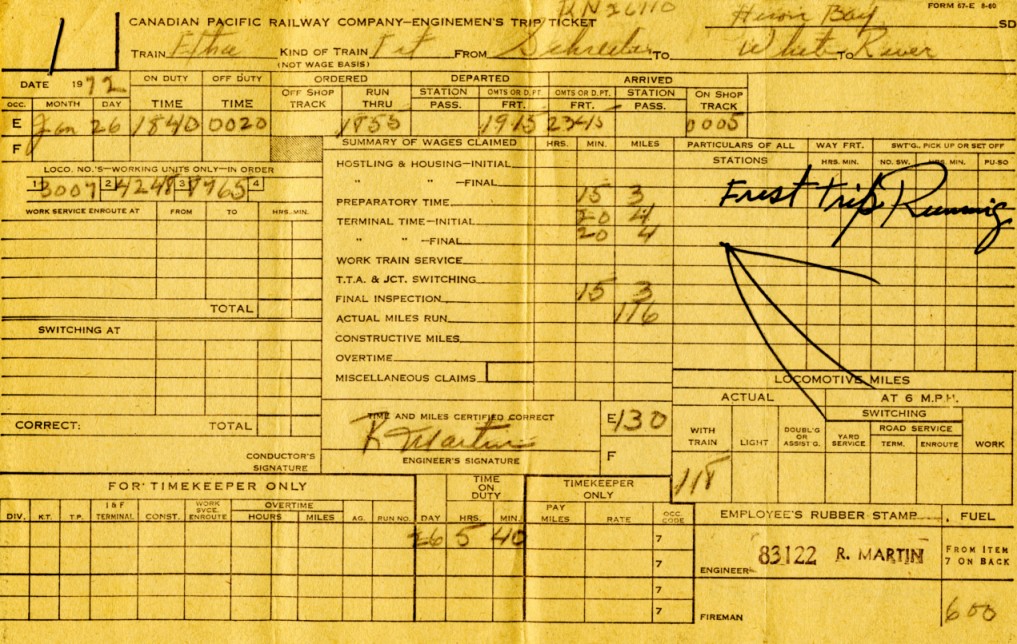

At the Throttle as a Locomotive

Engineer

Rolly's

first trip working solo as a locomotive engineer was in

January 26, 1972.

His power was 3007 (GP38, built 1971); 4248

(C-424, built 1966); and 8765 (RS-18, built

1958).

He left Schreiber at 1915hr and arrived at White River at

2345hr.

The format of the trip ticket has changed since Rolly's first

fireman job.

Just before I met him,

Rolly get 10 merit points for spotting a broken rail near

Steel Tunnel. Number 1 was the transcontinental passenger

train and the speed limit at this point was 45 mph. One

would

have to be pretty sharp to spot or feel something wrong.

Operating over

a broken rail could easily result in a derailment.

In the personnel record of a running trades

employee, there was a tally kept of merit and demerit

points. These were also known as "brownie points".

Accumulating a given number of demerit points would result

in being "held out of service" (suspension), or firing.

Handing out of merit points, such as this, was not common.

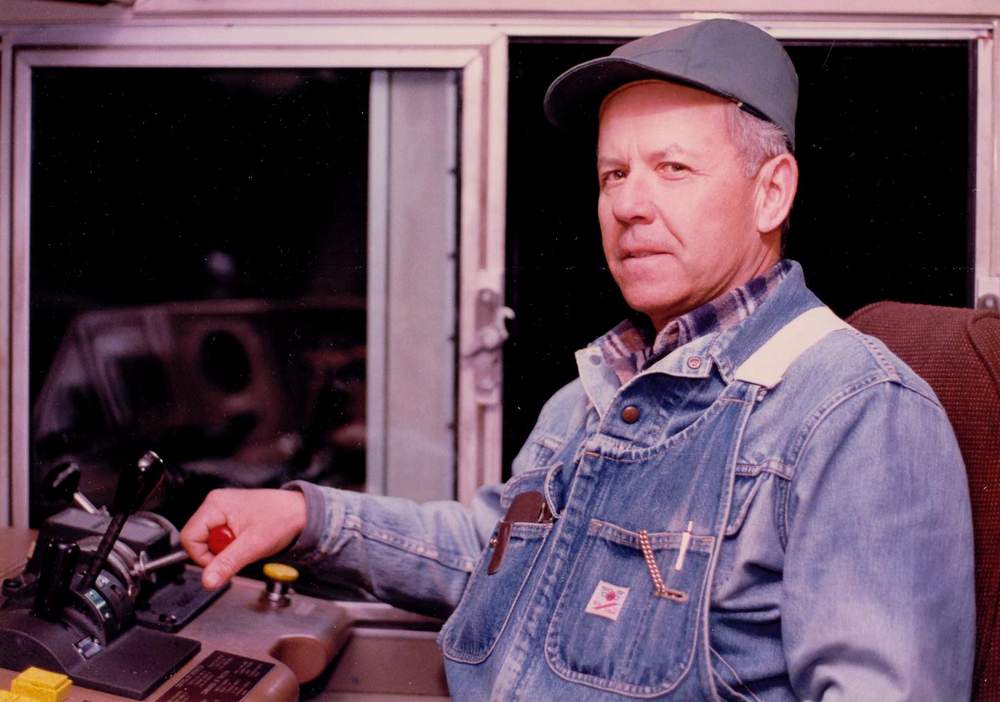

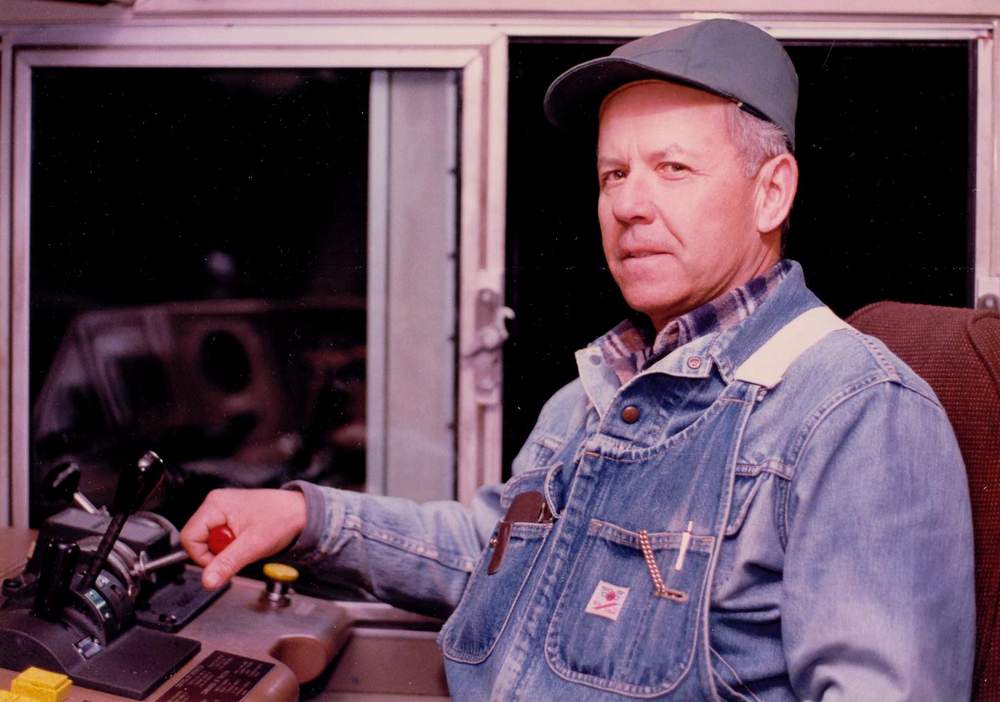

In the cab with Rolly

It takes special qualities to work successfully as a train

crewman along the north shore of Lake Superior,

and when you were in Rolly's cab you knew he was not your

average engineer ...

He seemed to have memorized every rule, regulation and train

order. He operated with an attentiveness and intensity that I

did not often see as a trainman. Rolly probably appreciated the

fact that I

followed my training to sweep out the cab immediately after

boarding,

because he expected the cab to be "as neat as a pin" at all

times. He did

not tolerate some of my trainmen peers who were not ready for

business

while working on his engines.

Other engineers expected you to call the approach and stop

signals. Rolly expected you to call every signal on the entire

subdivision. In my case, his reputation preceded him and I was

prepared, but nervous, during my first trip with him. Rolly was

right: just one missed signal could spell disaster and Rolly

watched for the first glimpse of each signal like a hawk.

Rolly knew and observed every rule, but somehow you always

felt you were moving a little faster with him. He was there to

get

the trains through with the greatest safety - BUT he was also

there

to get them over the road. When it was time to "hog 'er out"

Rolly was

really in his element.

Many times on the road there would be 'bell ringers' in the

locomotive consists. Traction motor ground relays, locomotives

low on

oil or water, and other malfunctions, would challenge an

engineer's ability

to keep the train rolling on some of the grades, or to get it

started

after a meet. Rolly made it his business to know the various

types of locomotives

well and he was resourceful and decisive when troubleshooting

was required.

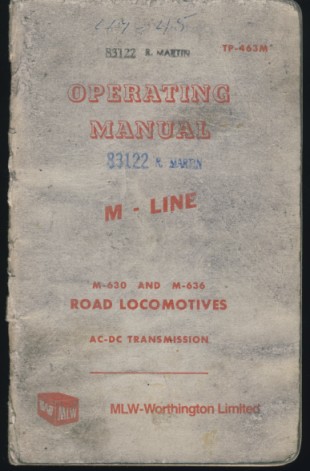

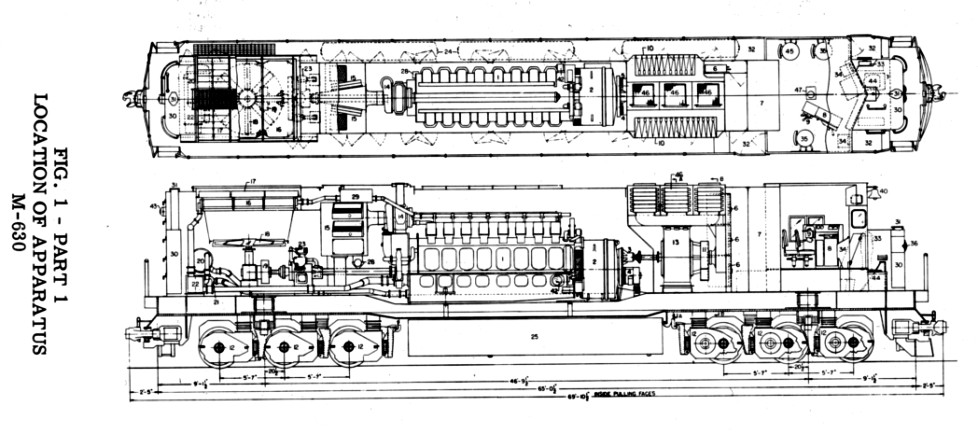

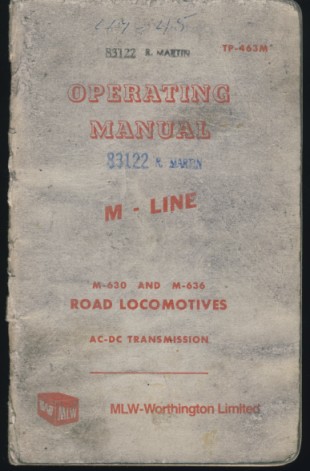

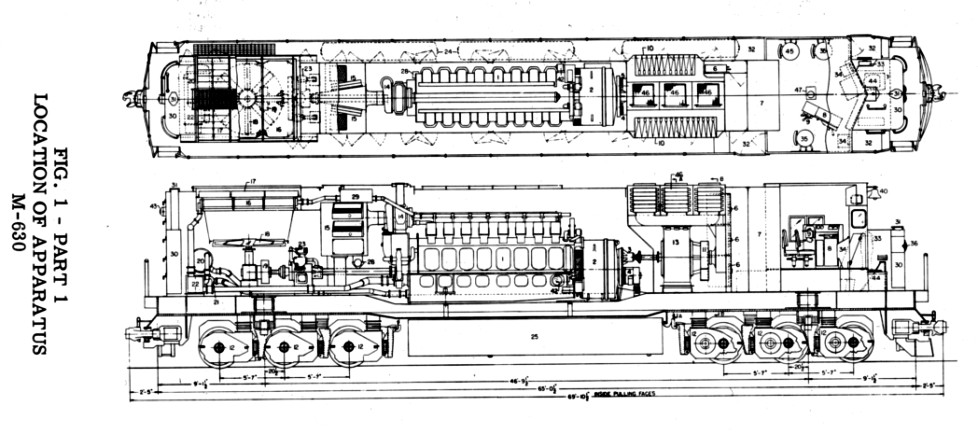

A locomotive manual which travelled thousands of miles in

Rolly's bag.

Below, the Alco-designed locomotive it helped to keep running.

Back: radiator and

cooling fan, air compressor, fluid reservoirs.

Centre: Diesel motor.

Front: electric

generator, blower ... and above: dynamic brake grids.

Below: 3400 gallons

diesel fuel.

On axles: electric

traction motors - all blown for cooling purposes.

The trainman sat in the first seat (circle) at the left of the

cab

and the former steam firemen were gone ...

having replaced retiring

enginemen.

While working as a trainman, I was therefore always the first

of the crew to arrive at our destination.

Rolly also shared his knowledge and experience with others.

In my case as a trainman, he explained the construction history

of the line along Lake Superior, pointing out the last spike

cairn. On the road, he helped me develop new skills to make me a

more professional railroader. He certainly was not afraid to

leave a nice, warm cab in a snowstorm

to show a new trainman how to effectively clean out a

snow-packed switch. Rolly spent a great deal of time and effort

training new engineers and helping them benefit from his years

of experience. Today, a number of Schreiber engineers carry on

in his tradition.

During the years I knew him, many of Rolly's locomotive consists

would

have looked exactly like this ... the 6 axle General Motors

locomotives

which were the CPR's workhorses for several decades at the end

of the

last century. As Schreiberesque as this photo appears, this

12,000

horsepower consist was photographed climbing just west of the

continental divide

in the Rocky Mountains in 1984. Once, I was talking to a CNR

hogger accustomed to bouncing

around in 4 axle GM power in the east ... he extended his arms

like The Sphinx

and said with admiration that these SDs rode like 'just like big

cats'.

At Schreiber, a very common sound was the whistle and whine of

these

locomotives' turbochargers. When starting a heavy train,

engineers

would first fiddle the throttle

back and forth between 0 and 1 for the first locomotive-length

of

travel ... to gently stretch out the slack and get the whole

train

moving. Careful modulation

around the low throttle settings continued, as sticky brakes

released

and the engineer got his first 'feel' of the train. All the

while, the turbos

would respond to each throttle setting ... by raising or

lowering their

tone at 100 decibels or so. Neither Rolly, nor any other

engineer, had any secrets from the citizens of Schreiber when it

came

to their application of tractive force as they got out of town.

The main power controls of an EMD SD40-2.

The main power controls of an EMD SD40-2.

Running 'Number One'

Rolly ultimately rose to

become Senior Man on the Schreiber Division and spent the

last several years of his career as engineer on The Canadian

between Schreiber and Thunder Bay. In 1989, he passed the

new and

difficult CROR rules examinations (the first major rulebook

revision

since 1962) with an average in the high 90s. He qualified

for

cabooseless operations as a "Locomotive Engineer/Conductor"

in May of

1989.

On

a cool summer morning in 1987.

Rolly and mate Dave Speer will be taking Number 1 to Thunder

Bay after it is serviced at Schreiber.

About the Rules change

Rolly's qualifications card from passing the new Canadian

Rail Operating Rules and cabooseless procedures exams.

The previous rulebook used by federally-regulated

railways

was effective (after the 1960 elimination of steam

locomotives) in

1962.

In 1990 the new CROR rulebook became effective. At the same

time,

vans (cabooses) were eliminated and new functions, such as

monitoring

the tailend telemetry device on freight trains, were added

to the

engineer's duties. This "Sense and Braking Unit" (SBU) and

its new

monitoring computer told the engineer when the tailend was

moving,

tailend trainline air pressure status, when the tailend was

clear at a

siding, and it allowed the engineer to make an emergency

brake

application from the tailend if there was a trainline defect

such as a

crimped air hose near the headend.

In the 30 years since the end of steam, there had been

significant

changes in railway technology ... many of them due to 'main

frame'

central computerization with 'dumb terminals' - such as

teletype

machines which 'saved data to punched paper tape' -

distributed across

the railway in offices.

During the next major wave of change, 'computers'

became

small, cheap, and reliable enough to mount in

railway equipment in the field ... to regulate key functions

on

locomotives; to synthesize frequencies in radios instead of

using

crystals; to give hotbox scanners a

'voice'; to

bang

around on the last coupler of the train inside the

Sense and

Braking Unit. You could say it was the 'computer'

which spelled the end

for the conductor's van on the tailend.

Retirement

At 0330hr on December 12, 1989, Rolly brought Number 2

into Schreiber station for the last time.

It was minus 30 degrees as Rolly stepped down from the VIA

6433 into retirement.

Rolly's retirement gathering in

December 1989.

Left to right: Bill Needham

retired Schreiber Terminal Supervisor, Lauri Halonen

trainman, Mike Scott diesel maintainer, David

Speer engineer and Rolly's mate on Number 1, Doc

Nesbitt retired engineer, D’Arcy McGuire

retired engineer, Jack Anderson retired conductor, Jack

Pollock conductor, Rolly Martin, Camille

Peras retired conductor, Sonny Morrow retired

conductor, Dudley Cardiff retired engineer, Bob

Krause retired engineer, Mike McGrath retired

engineer.

Rolly and Thérèse at Rolly's

retirement.

Always eager to learn

and experience new things, Rolly and Thérèse enjoyed travel,

including a cruise up the coast of Alaska and a grand Asia

Pacific tour. Of course, Rolly maintained a great interest in

the latest developments on "the road" as well.

During our visits over the years, Rolly and Thérèse did

everything with us from harbour tours of Thunder Bay, to

visiting Ouimet Canyon, to fishing expeditions with Dave Speer

for Lake Trout at Rossport, to visiting various sites of

historical interest along the shores of Lake Superior.

Through their generosity to us over

three decades, Rolly and Thérèse

made immeasurable contributions

to my "Schreiber experience".

Through this website, I

intend to keep Rolly snapping the throttle through its

notches, cycling the air,

and calling all the signals on the

Heron Bay and Nipigon Subs for years to come.

Back to

sitemap