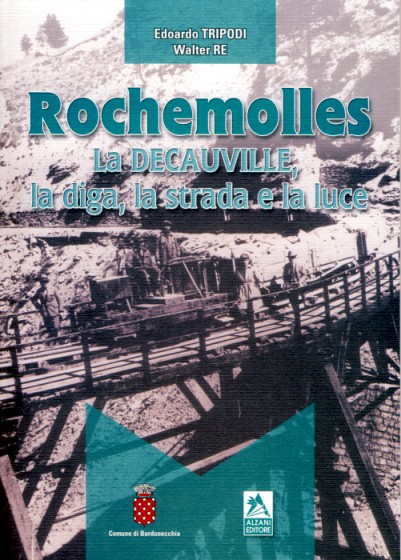

the Decauville

the Dam, the Road, and the Light.

Edoardo Tripodi

Walter Re

A new railway book from Italy.

Edoardo is the Director of Cardiology at a hospital in Turin ... and has a lifelong interest in railways.

He recalls his parents mentioning that during a 1947 trip to Rochemolles,

in northwestern Italy, they saw a train running up to the dam ...

It is Dr

Tripodi's interest in researching this intriguing mystery from the

years before he was born, which

yields

this

fascinating exploration of vanished technologies, the

modernization

and

development of Bardonecchia,

and modern 'railway archeology' photos of local artifacts.

Walter Re, his friend and

co-author, provides illustrated vignettes of the region's past. One

details the various mountain roads through history which lead to

Rochemolles. The placement of a generator in the local grist mill

provided the first electricity and established a local public

electrical utility - before the concrete dam was built. An itinerant

priest with an interest in technology developed a clock-based device to

efficiently regulate the public lighting so electricity was not wasted,

and a number of photographs show details of this ingenious wood and

metal invention.

Many of the scenes shown came from glass photographic plates given as a gift to Mr Re by Valerio and Silvio Durante. The plates had been found languishing in their attic. Originally, they were made by a professional photographer who lived in the area. Mr Re, an amateur photographer, lovingly restored and preserved these priceless historical images of the area's past and its development.

Another set of photographs came from Paolo Avigdor, someone with a great love of Bardonecchia. His father Emilio Avigdor (1892-1957) had been a Knight of the Crown of Italy and a key figure in the electrification of the railway line to Modane, 1920-1927. The family was forced to leave Italy with the enactment of 'racial laws' in 1939 and they emigrated to Brazil. His father never returned to Italy, but Paolo returned and lived in Italy for many years. He loved to vacation in Bardonecchia. Eventually he presented Mr Re with a collection of images preserved by his father.

It is the opportunity to present messages from "long ago and far away" such as Mr Re's

which make it such a privilege to put together the accounts of history you see on this website.

Many of the scenes shown came from glass photographic plates given as a gift to Mr Re by Valerio and Silvio Durante. The plates had been found languishing in their attic. Originally, they were made by a professional photographer who lived in the area. Mr Re, an amateur photographer, lovingly restored and preserved these priceless historical images of the area's past and its development.

Another set of photographs came from Paolo Avigdor, someone with a great love of Bardonecchia. His father Emilio Avigdor (1892-1957) had been a Knight of the Crown of Italy and a key figure in the electrification of the railway line to Modane, 1920-1927. The family was forced to leave Italy with the enactment of 'racial laws' in 1939 and they emigrated to Brazil. His father never returned to Italy, but Paolo returned and lived in Italy for many years. He loved to vacation in Bardonecchia. Eventually he presented Mr Re with a collection of images preserved by his father.

Valerio Durante died in 1999, and

is buried in the Rochemolles cemetery.

Paolo Avigdor, son of an exiled Knight of the Crown, first cousin of Primo Levi, died in 2002 and is buried at Bardonecchia.

You can perhaps understand the depth of history and affection for Rochemolles and Bardonecchia which has gone into this book.

Paolo Avigdor, son of an exiled Knight of the Crown, first cousin of Primo Levi, died in 2002 and is buried at Bardonecchia.

You can perhaps understand the depth of history and affection for Rochemolles and Bardonecchia which has gone into this book.

Update: July 2010

After posting this page ...

it was a surprise and an honour to receive a message in Italian from Mr Re.

(Mr Re also speaks French because this region of Italy is near the border with France)

Mr Re referred to his contribution to the Rochemolles book ...

vignettes about the unique culture of citizens living in remote mountain settlements.

Through GoogleTranslate Italian-English,

then "Romance language review (my French)" of the results ...

here is my interpretation of Mr Re's message.

(i.e. Any errors are mine !)

After posting this page ...

it was a surprise and an honour to receive a message in Italian from Mr Re.

(Mr Re also speaks French because this region of Italy is near the border with France)

Mr Re referred to his contribution to the Rochemolles book ...

vignettes about the unique culture of citizens living in remote mountain settlements.

Through GoogleTranslate Italian-English,

then "Romance language review (my French)" of the results ...

here is my interpretation of Mr Re's message.

(i.e. Any errors are mine !)

|

Walter Re comments that to the book, he

contributed ...

... some small stories of

Rochemolles life, arising from the construction of the Rochemolles dam.

The stories are of a small mountain village at well over 1600 meters

[above sea level], and its people who have lived for centuries in a

hostile environment with a deep mountain culture and environment.

These people, who lived in isolation for many months of the year, used the short summer to obtain the winter staples of wood and hay. Nearly all of these people were able to read and write (nearly all 400 people were literate in 1851). In addition, almost everyone spoke and were able to understand four languages (the local patois ; French - that was the cultivated language of documents and books ; Piedmontese - the language from the lower Susa Valley ; and also Italian). Many knew "arithmetic" and some understood something of Latin. During the long winters, some became masters and teachers, later moving into the neighbouring valleys and France to teach others what they knew. But they knew perfectly well the mountain and its delicate balance : they had written the rules (bandi campestri - bans champetres) to manage and rule their territory as early as 1700. Unfortunately, modern Rochemolles was forever devastated by avalanches: the last major one being in 1961. This coincided with the period in which the "community spirit" of the area faded - the spirit which had helped the remote settlements survive for many centuries. There has been no strength or will to recover this - even the people have changed with new modes of living seeming easier and more attractive. Just as the Sommeiller Glacier has gradually melted, so has the spirit of the community. And without wanting to be nostalgic or romantically linked to their past and to their roots ... we have all lost a piece of history and culture. |

It is the opportunity to present messages from "long ago and far away" such as Mr Re's

which make it such a privilege to put together the accounts of history you see on this website.

A Quick overview of the physical features ...

I didn't want to appropriate any of Edoardo's images ...

so I doodled my own Decauville (railway line) map above.

The deep glacier-gouged valleys of today's mountain torrents influenced two human structures here ...

1. The construction of a graceful concrete arch dam in the 1930s.

2. The narrow gauge Decauville-style railway line (yellow dots).

It travelled up the gullies to cross them at about the same roadbed level,

but using a shorter bridge span.

It was the Decauville which was essential for the building of the dam,

and to support the other activities which Edoardo details in his book.

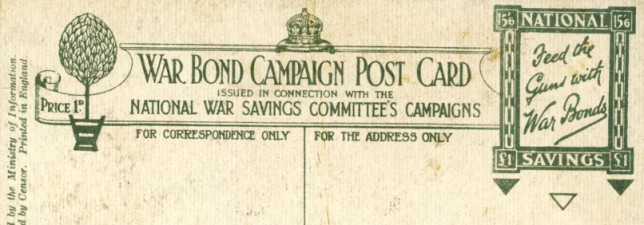

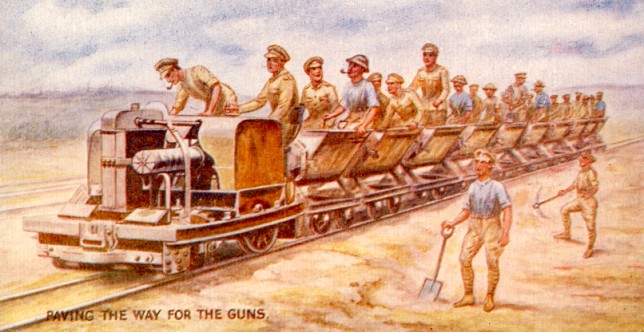

Decauville references attract Emails !

Previously, one Decauville image from this website was useful to an archaeologist in identifying a truck dredged up during the current Panama Canal widening. More recently, Edoardo asked to use the image below in his book ... as the Simplex gasoline locomotive matches equipment used on the Rochemolles dam, including that shown on the cover of his book.

My original interest in purchasing the old postcard was its connection to the Canadian Overseas Railway Construction Corps, which worked under British command to build and maintain railway lines to the trenches during the Great War.

Building railway lines through Canadian Shield muskeg ... and the expert use of horse-drawn scrapers ('farm equipment') to grade roadbed ... were valuable skills Canadians brought to the Railway Construction Corps. Often narrow gauge railways were constructed through water-logged landscape and settlements torn apart by shells. The ability to improvise transportation through Great War 'muskeg' was essential for moving troops, the wounded, supplies and ammunition.

Edoardo's and Walter's 150 page

book is absolutely

full of diagrams, maps, reproduced documents, and photographs of the

area between Bardonecchia and the Rochemolles dam.

So, without understanding the book's Italian text, it is still possible to appreciate a great deal of the local human history and the technology used around Rochemolles. Knowing French and using Google Translate have also helped. We have corresponded in French - sort of midway between English and Italian.

Researching the history of the area, I found I could present this little precis of Edoardo's and Walter's book and some interesting railway history of the surrounding area WITHOUT trying to translate and explain the many details covered in his fine book ... I think I will enjoy understanding the book in its entirety over a longer period of time.

... It would also be difficult for an authors to see their painstaking history ... dissected inaccurately and rehashed with misunderstood facts due to the language barrier !

So, without understanding the book's Italian text, it is still possible to appreciate a great deal of the local human history and the technology used around Rochemolles. Knowing French and using Google Translate have also helped. We have corresponded in French - sort of midway between English and Italian.

Researching the history of the area, I found I could present this little precis of Edoardo's and Walter's book and some interesting railway history of the surrounding area WITHOUT trying to translate and explain the many details covered in his fine book ... I think I will enjoy understanding the book in its entirety over a longer period of time.

... It would also be difficult for an authors to see their painstaking history ... dissected inaccurately and rehashed with misunderstood facts due to the language barrier !

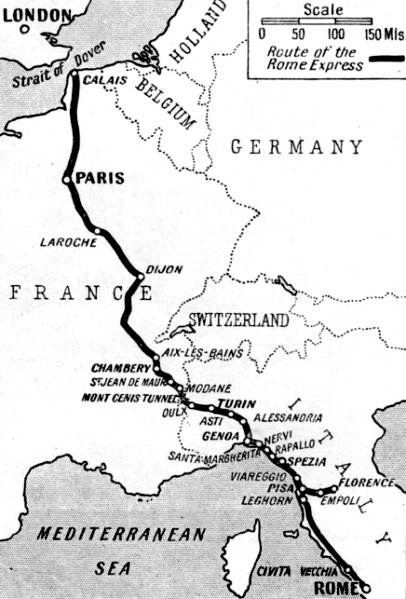

The Geographical Setting

This 1930s map presents the relative location of Rochemolles in Europe.

It is in the mountainous border area between Modane, France and Turin, Italy.

My story will discuss the circumstances linked to the Mont Cenis Tunnel.

The 'Mont Cenis Tunnel'

- about 12.2 kilometres in length - was completed in 1871.

(For a Canadian historical context: The 'old' and 'long' Canadian Pacific Railway Connaught Tunnel - completed in 1916 to get the railway away from Rogers Pass avalanches - is about 8 kilometres long. It was 'so long' that the urban legend developed that white sightless mice had evolved within it ... as generations of them had happily resided inside ... surviving only on grain leaking from passing freight trains. And 1871 was the date British Columbia entered Canadian Confederation ... and the building of a 'Canada Pacific Railway' within 10 years was made a condition of B.C.'s joining Canada.)

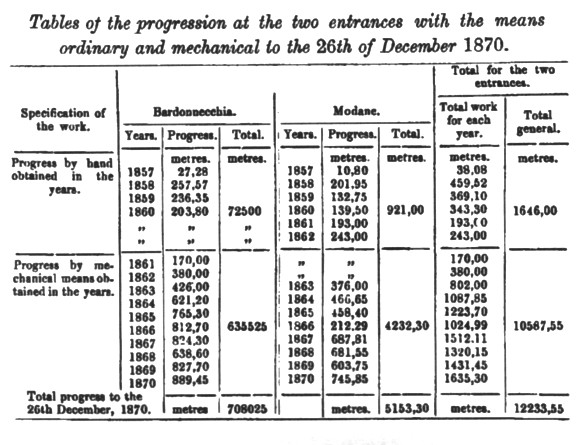

As you will read, the impossibility of sinking vertical shafts for ventilation, and to start additional intermediate tunnel work faces at Mont Cenis, resulted in innovation ... Sommellier and other engineers developed mechanical drilling machines ... operated by compressed air ... which was piped all the way to the work faces ... from compressors driven by falling mountain torrents outside the portals. For breathing air, and to clear blast gases and rock dust, the rate of compressed air ventilation was temporarily increased. Being the first long railway tunnel attempted through the Alps ... Mont Cenis and the technological innovations developed to complete it made history. A table contrasting the progress made with traditional hand drilling and blasting ... with the remarkable progress of the compressed air perforators ... appears later on this page.

Below is a map from the 1920s.

Underlined in red, you can see Bardonecchia ... and the Rochemolles dam would be to the north, just under the 'ju' of 'Pt de Frejus'.

The green underlined 'Frejus' name is often used (with greater geographical accuracy!)

when the Mont Cenis Tunnel is referred to in Italian - il traforo del Frejus.

In recent decades a highway tunnel with a similar Italian name has been built in the area as well.

The 'Mont Cenis' Tunnel name has stuck partly because the mountain pass

in the shadow of Mont Cenis was a principal route between Italy and France before the tunnel was completed.

The fact that Napoleon built barracks in, and roads through, the pass ... also popularized the Mont Cenis name ...

as historical accounts of his campaigns were studied, I'm guessing.

Since this map was printed, the Mont Cenis orange 'pocket' has been enveloped by the French border.

... And the Savoy and Piedmont areas were among the larger land masses changing hands during the last two centuries.

So the 'old' overland mountain pass route was St. Michel, Lanslebourg, Mont Cenis pass, Susa - the green dots.

The green dots also mark the general route of the short-lived Mont Cenis Railway Company 1868-1871.

The 'new' post-1871 mainline railway route through 'The Tunnel' is from Modane to Bardonecchia - the towns underlined in red.

You can see the railway mainline (bold black line) running from St. Michel to Turin. Susa is on a branchline.

A point recounted in history helps explain the rationale for building a tunnel here -

the tunnel idea was first suggested back in 1832 - before railway and tunneling technology had matured sufficiently ...

Some reflected that the Alps along Italy's northern border had not protected it from military invasion ...

so there was nothing to be lost by opening this first major breech in the mountain wall for travel and trade.

The Rochemolles Features

within

The Geographical Setting

Distances ...

Modane to Lanslebourg is about 26 km by road.

Lanslebourg to Susa is about 36 km by road.

The current railway: along the valley from the west to Modane, Bardonecchia, Susa is shown by a thin black line.

(Note: La Ramasse is really at the NORTH end of the Mont Cenis pass - not the south end as shown.)

The Mont Cenis Pass (right)

The lake in the pass has been enlarged by a dam at the south end, flooding the remains of some historic buildings in the pass.

The border has now slid to the south so the pass is now mainly in France.

The red dots through the pass show what I believe was the general location

of the 1868-1871 Mont Cenis Railway Company in the pass.

(However, the green dots in the previous diagram above show its total length from St. Michel to Susa.)

This little mountain railway was an experimental effort to improve on pedestrian or horse coach travel ...

up the often snowy and stormy mountain slopes and through the pass.

The tunnel was completed more rapidly than expected so this unique railway operation was terminated after only 3 years.

The 'Mont Cenis Tunnel' (left) and the Rochemolles dam.

The tunnel opened in 1871.

The Rochemolles dam was built in the 1930s ...

Up from the south tunnel portal area and mainline at Bardonecchia, a funicular railway was built ...

to haul cement, construction materials and workers up the steep slope.

At the top of the funicular railway,

the passengers and cargo reached the relatively level roadbed,

of the Decauville-style narrow gauge railway line ... north ... ending at the dam.

The Rochemolles dam provided hydro-electricity for domestic and industrial uses.

It also provided power for the electric locomotives of the state railway,

particularly those operating through the Mont Cenis tunnel.

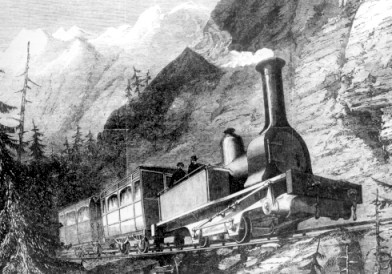

The Mont Cenis Railway

Company

1868 to 1871

(the temporary railway through the pass)

1868 to 1871

(the temporary railway through the pass)

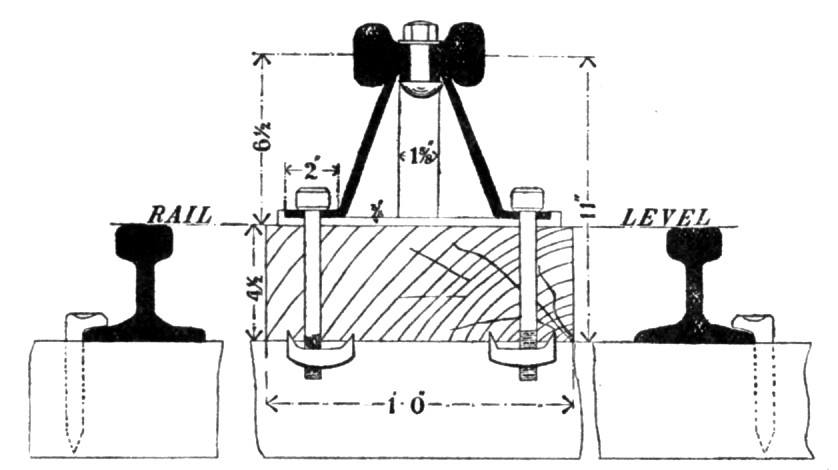

'Artistic licence' presents only a frail central rail with small power/brake wheels.

from The Civil Engineer and Architect, October 1, 1866

" In consequence of the time

which

it will take to complete this [Mont Cenis] tunnel, the idea has been

conceived of

constructing a temporary railway over the top of the Mont Cenis. There

is a very good road over the mountain, along which it is proposed to

lay this railway. The total elevation of the pass is 7000 [feet] and of

the mountain 11,000. When Mr [John

Barraclough] Fell [1815-1902]

went three or four years ago to examine it, with the view of taking a

railway over it, he found it too steep for any ordinary railway worked

in the usual way, and he was therefore obliged to adopt a new system,

the principle of which I will now explain. In ordinary railway working

we trust, as you are aware, to the adhesion between the vertical

driving wheels of the engine and the bearing rails of the permanent

way, as the means by which the steam-power is applied to propel a

train. And in order to get extra adhesion to take heavy loads up steep

gradients, we are obliged to increase the weights of our engines, and

the number of their driving wheels, in proportion to what we require.

But in mounting a gradient of 1 in 12, with bad adhesion, such as you

are liable to find on the Mont Cenis, sometimes not more than one-tenth

or

even one fifteenth an engine, ever so heavy, would only be able to take

itself up, with perhaps a very light train. So Mr Fell has thrown off

extra weight, and made an engine partly of steel; and he has employed

for extra adhesion, a central rail, laid in the centre between the

other two, with horizontal wheels on the engine to bite upon it, and so

pinch their way up the incline. His second engine weighs 17 tons, which

added to 24 tons of pressure between his horizontal wheels and middle

rail, affords a total adhesion of 41 tons; and it will do the work,

therefore, on steep gradients and slippery rails, of an ordinary engine

weighing 36 or 40 tons, without being killed - so to speak - by its own

weight.

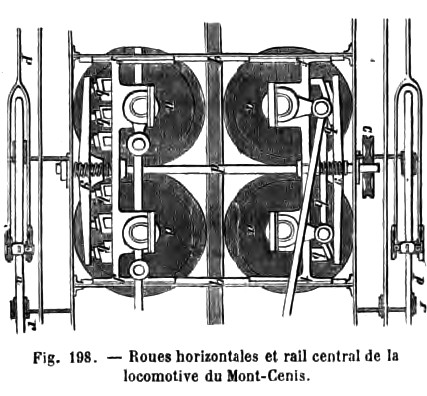

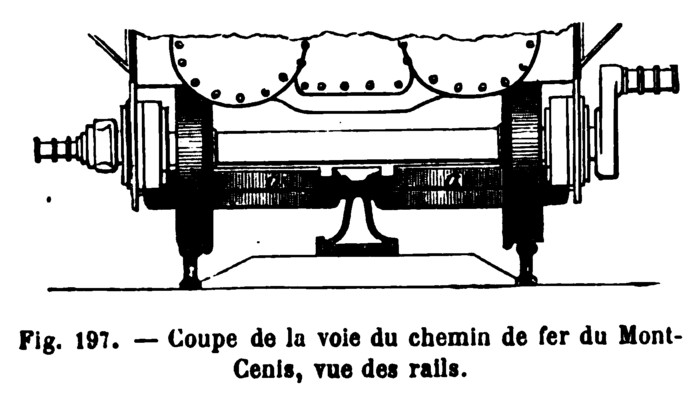

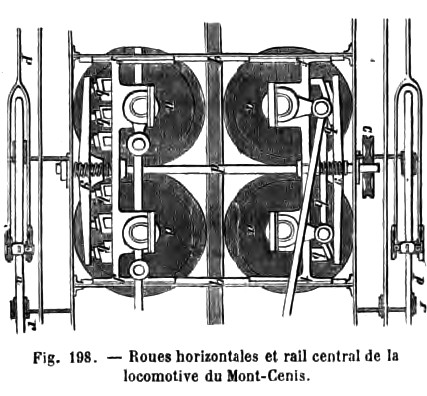

Under the Fell locomotive and seen from above: The power/brake wheels gripping the central rail.

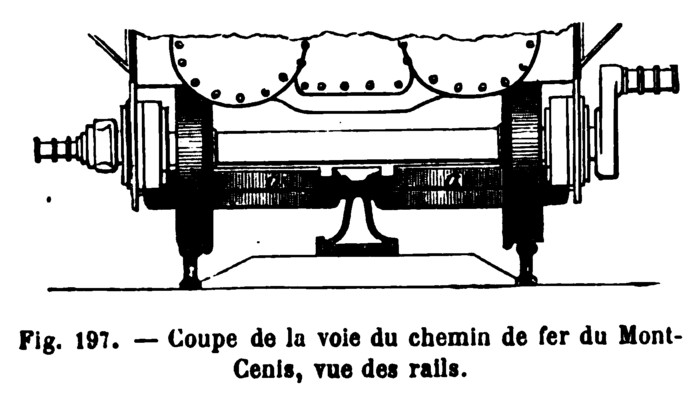

From the locomotive front: the vertical and horizontal power wheels.

The central rail was only built on the steeply sloping sections of the line.

Otherwise, the locomotive worked 'conventionally' on just two rails.

" Mr. Fell first tried this system - which was patented so far back as 1830, but had never been reduced to practice - at Whaleybridge, with the assistance of Mr. Brassey, in this country, and the experiments there were so successful, the he then constructed an experimental railway on the Mont Cenis, which has been worked now for many months with great success. About 20 minutes' walk above Landslebourg, where the ascent of the Mont Cenis commences, he has constructed a mile and a quarter of railway, on the zig-zags of the steepest part of the mountain. The steepest gradient is on it is 1 in 12, the average gradient 1 in 13. The curves are very sharp, with a radius of only 40 metres, or 131 feet, round the corner of the zig-zag. On this experimental line, with his second engine, he has taken up a weight of 16 tons, which is equal to 50 passengers with their luggage at the rate of 8 miles an hour; and there is no doubt he will be able to run without any difficulty for the 48 miles which he has to traverse with his railway, in four hours' whereas it takes twelve by the diligence in bad weather, and eight hours in the best of weather.

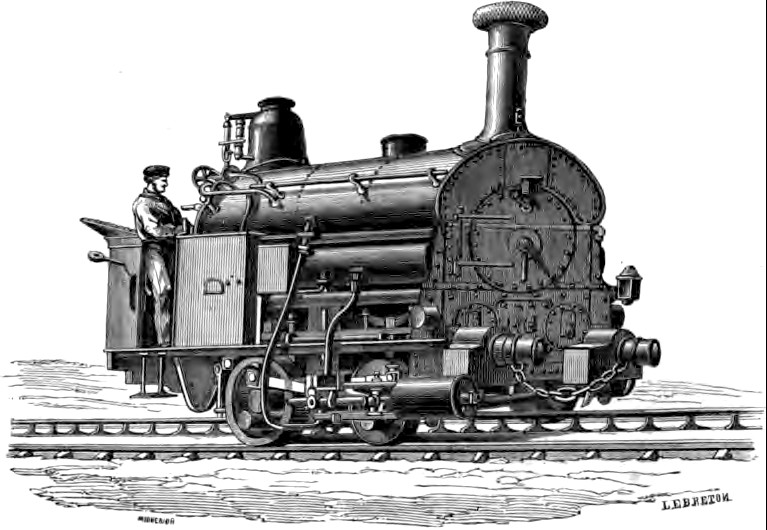

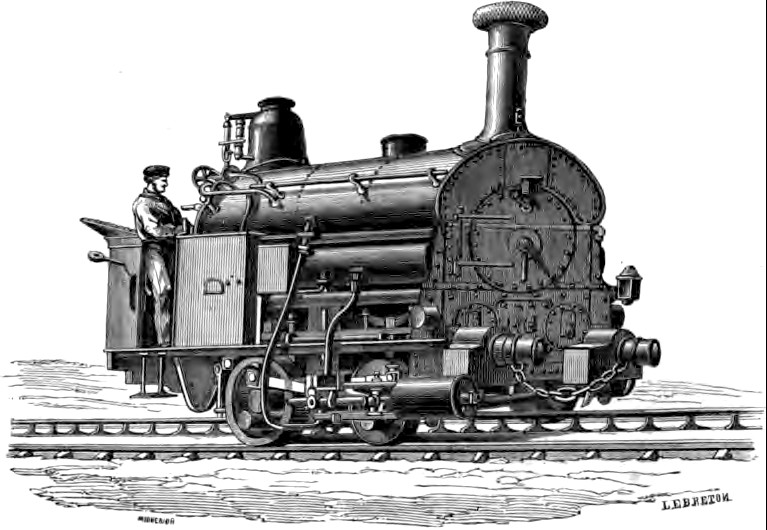

Fell Locomotive from Mont Cenis

from 'Merveilles de la Science', Louis Figuier

This 'saddle tank' engine places the water reservoir over the boiler and driving wheels:

1. More weight on conventional driving wheels for better traction.

2. The firebox and boiler (below) naturally preheat the water storage tank (above) for increased fuel efficiency.

3. The short locomotive frame and lack of a tender are better suited to working around sharp curves.

" There will be nine miles and a half of covered way on the mountain ['snow sheds' enclosing the track], to avoid any risk from the action of snow and avalanches, and that the traffic may be worked punctually and with safety in the worst of weather. One very important element in the system, is the greatly increased degree of safety that may be obtained. The central rail, properly applied, will prevent the possibility of a train running off the line' and you may easily conceive that it is most important to have this extra means of safety round very sharp curves, and at the edges of precipices, on the slopes of Mont Cenis.

" In running down this railway at first, it feels - so to speak - rather like sliding down the roof of a house; but the breaks [sic] acting upon the middle rail afford a powerful means, in addition to the ordinary breaks, of stopping the train and I have seen the experimental train, travelling at the speed proposed to be employed, brought to a stand with a dozen yards on the steepest part of the slope. "

Under the Fell locomotive and seen from above: The power/brake wheels gripping the central rail.

From the locomotive front: the vertical and horizontal power wheels.

The central rail was only built on the steeply sloping sections of the line.

Otherwise, the locomotive worked 'conventionally' on just two rails.

" Mr. Fell first tried this system - which was patented so far back as 1830, but had never been reduced to practice - at Whaleybridge, with the assistance of Mr. Brassey, in this country, and the experiments there were so successful, the he then constructed an experimental railway on the Mont Cenis, which has been worked now for many months with great success. About 20 minutes' walk above Landslebourg, where the ascent of the Mont Cenis commences, he has constructed a mile and a quarter of railway, on the zig-zags of the steepest part of the mountain. The steepest gradient is on it is 1 in 12, the average gradient 1 in 13. The curves are very sharp, with a radius of only 40 metres, or 131 feet, round the corner of the zig-zag. On this experimental line, with his second engine, he has taken up a weight of 16 tons, which is equal to 50 passengers with their luggage at the rate of 8 miles an hour; and there is no doubt he will be able to run without any difficulty for the 48 miles which he has to traverse with his railway, in four hours' whereas it takes twelve by the diligence in bad weather, and eight hours in the best of weather.

Fell Locomotive from Mont Cenis

from 'Merveilles de la Science', Louis Figuier

This 'saddle tank' engine places the water reservoir over the boiler and driving wheels:

1. More weight on conventional driving wheels for better traction.

2. The firebox and boiler (below) naturally preheat the water storage tank (above) for increased fuel efficiency.

3. The short locomotive frame and lack of a tender are better suited to working around sharp curves.

" There will be nine miles and a half of covered way on the mountain ['snow sheds' enclosing the track], to avoid any risk from the action of snow and avalanches, and that the traffic may be worked punctually and with safety in the worst of weather. One very important element in the system, is the greatly increased degree of safety that may be obtained. The central rail, properly applied, will prevent the possibility of a train running off the line' and you may easily conceive that it is most important to have this extra means of safety round very sharp curves, and at the edges of precipices, on the slopes of Mont Cenis.

" In running down this railway at first, it feels - so to speak - rather like sliding down the roof of a house; but the breaks [sic] acting upon the middle rail afford a powerful means, in addition to the ordinary breaks, of stopping the train and I have seen the experimental train, travelling at the speed proposed to be employed, brought to a stand with a dozen yards on the steepest part of the slope. "

... end of The Civil Engineer and Architect, October 1, 1866

"Before the opening of the Mont Cenis Tunnel in 1871, J.B.Fell built, on Napoleon's road over the pass,

a line in which the locomotives gripped a central horizontal rail.

It had its hazards, especially at avalanche time, but for three years it carried passengers, goods and the overland Indian Mail."

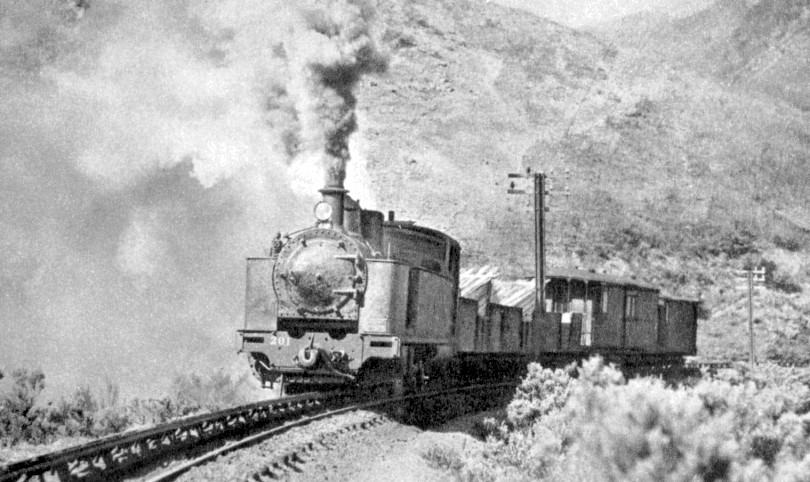

A modern application of Fell technology.

An English-built Fell locomotive, built 1878, scrapped 1956.

Working up the 'Rimutaka Incline' in the Wairarapa district of New Zealand in 1955 shortly before operations here ended.

Track diagram below from: 'Light Railway Construction' (1902)

" ... a double-rail is laid

horizontally at the centre of the track a little above the regular

rail-level, to enable a pair of horizontal driving-wheels in the

specially made Fell engines to grip it firmly. When the steep incline

is reached, and the horizontal wheels have gripped the rail, the steam

is admitted to the cylinders working them, and unless the supply is

ample, shut off from those working the adhesion drivers [the regular

wheels].

"This was used on the original Mont Cenis railway, where there were gradients of 1 in 12 [about 4 times steeper than the CPR or North American 'standard'] , but has to a great extent been superseded by the Abt rack-rail system, although it is better adapted to curves of less than 5 chains [330 feet] radius."

"This was used on the original Mont Cenis railway, where there were gradients of 1 in 12 [about 4 times steeper than the CPR or North American 'standard'] , but has to a great extent been superseded by the Abt rack-rail system, although it is better adapted to curves of less than 5 chains [330 feet] radius."

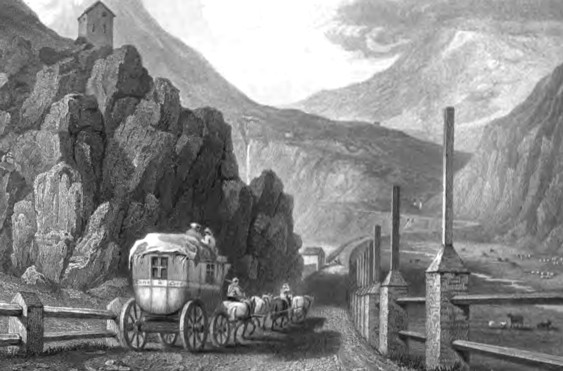

A Yorkshireman's Trip to Rome in 1866

Over the pass by horse-drawn coach.

The old way ...

In 'A Yorkshireman's Trip to

Rome in

1866' ... William Smith, Jun., F.S.A.Edin., & F.R.S.L. ...

describes the railway passenger service of France ending at St. Michel

during the

period the Mont Cenis Tunnel was being constructed. It was from St.

Michel that his journey by diligence began. These stagecoaches were

described as 'two lumbering unwieldy machines'. For the record, the

diligence departed St. Michel at 13hr, pulled by six horses.

" When we reached Modane a halt was made, and when we next started we had three horses and eleven mules in front of us, managed by the driver on the box, two postillions, and two persons who walked by the side of this imposing cavalcade and used two enormous whips with more severity than the circumstances of the case required. ... Near Modane we had passed the little village of Fourneaux, to the right of which about three hundred feet above the level of the main road is the northern entrance of Mont Cenis tunnel; the works connected therewith appear of an extensive character, including, so far as we had an opportunity of seeing, a vast accumulation of machinery. This idea of a tunnel through the Alps occupied for years the minds of French and Italian engineers, but it is to the latter, that the credit must be given of working the idea into a practical shape and of having hitherto prosecuted with commendable zeal, one of the most stupendous works ever undertaken by any people. To pierce a tunnel seven and a half English miles through hard rock seemed a hopeless task, especially as it was impossible to provide the usual means of ventilation, by means of air shafts; but this problems has been solved, and time, we believe, will see the work brought to a successful termination. The estimated cost of the tunnel is 5,876,000 pounds, of which the French government are to pay two-thirds and the Italian government one-third. The works have already been in progress eight years; and one-half of the distance has been pierced, and it is expected that the work will be completed before the end of the year 1875.

" We halted for half-an-hour at the 'Hotel Royal' in the wretched-looking village of Lans-le-bourg, the houses in which, are little better than cabins and are occupied by persons, who are evidently steeped in poverty and ignorance. Their chief employment is that, of conveying merchandise over the mountain and occasionally assisting to clear the roads from snow. [They couldn't eat the hotel food] We went outside, and occupied the time by making a survey of the locality, which resulted in the discovery of wretchedness and misery, which I suppose could not be surpassed, even in the back slums of our large towns in England. Surely some one is responsible for this sad state of things and we trust that the day is not far distant when this evidently semi-barbarous people will be taught some of the lessons of civilization, and at the same time, some of the lessons of true religion also. Just as we were leaving the village of Lans-le-bourg we passed a large wooden cross, and a little beyond this the small chapel of St. Antoine, where travellers used to hear mass before adventuring into the pass. A priest is still obliged to say it there if required, but our party did not avail themselves of his services.

" The highest point of the pass is 6780 feet above the level of the sea, but only 2000 feet above the valley of Lans-le-bourg, yet what an interminable distance it seemed by the zigzag course we took. Tired of turning corners, we got out and walked, not, however, following the road, but taking the sharp cross-cuts. As we walked along, we passed several houses of refuge, one of which we entered, and a most squalid and comfortless place it was. Twenty-three of these houses are placed at intervals along this pass, and the persons who occupy them live rent free, and have 15d. a day allowed - a miserable pittance, for which they are expected to keep the road clear from snow, to assist travellers who may have lost their way, and give warning of avalanches. These houses are often so buried in snow, that it is no uncommon thing for the women and children living in them, to be unable to step out of doors from autumn to spring.

Going up into the pass.

" Near to refuge No. 20, we came upon a line of railway in course of construction which is intended to cross the mountain instead of going through it. The line is laid down on the common road, but whether it will success is a matter for speculation, at present, it serves one useful purpose, that of protection to the diligence. The incline is of one yard in twelve, and a peculiarity of construction of this novel railway is a middle rail, the projecting parts of which are bitten or pressed by the horizontal driving wheels of engines constructed for this purposes. The engines will also have to work snow ploughs to clear the line of accumulations of snow. This singular line of railway was opened a few months ago, and the engineers who tested its safety, report most favourably, and predict that it will speedily supercede travelling by diligence over the Mont Cenis. We confess that we should prefer the latter mode rather than the first-named.

" We were passing from the genial warmth of the valley to the chilly regions of snow, and before we reached the summit of the pass, our conveyance had to take its course between walls of snow, which rose on either side to the height of several yards. ... The summit, or rather the highest part of the mountain which the road traverses is encircled with other mountains, objects of singular sublimity, one of which rises to the height of 18,000 feet, 6000 feet above the point we have at present attained.

In the Mont Cenis Pass.

[They later descended from the pass] " We were soon tearing along those awful zigzags, which conduct the road on its downward journey, on that ever to be remembered day, I cannot but wonder at the composure with which we travelled over so many miles, where precipices of fearful extent abounded - where rocks seemed impending over our heads, and a rushing torrent was careering along hundreds of feet below us - all these and the fearful speed at which the descent was made was certainly enough to make us feel somewhat nervous. ... The distance from the summit of the pass, to Susa, at the foot of the Alps, where our journey by diligence was to terminate, is 26 miles, which we accomplished in less than three hours.

" When we reached Susa, though we had been travelling sixteen hours with slight intermission, and nine of these hours we had been cooped up in a diligence, we scarcely felt a sense of fatigue, so much had the ever-changing scenery and the bracing air of the Alps kept mind and body in a state of joyous and pleasurable excitement. "

... end of ... A Yorkshireman's Trip to Rome in 1866

" When we reached Modane a halt was made, and when we next started we had three horses and eleven mules in front of us, managed by the driver on the box, two postillions, and two persons who walked by the side of this imposing cavalcade and used two enormous whips with more severity than the circumstances of the case required. ... Near Modane we had passed the little village of Fourneaux, to the right of which about three hundred feet above the level of the main road is the northern entrance of Mont Cenis tunnel; the works connected therewith appear of an extensive character, including, so far as we had an opportunity of seeing, a vast accumulation of machinery. This idea of a tunnel through the Alps occupied for years the minds of French and Italian engineers, but it is to the latter, that the credit must be given of working the idea into a practical shape and of having hitherto prosecuted with commendable zeal, one of the most stupendous works ever undertaken by any people. To pierce a tunnel seven and a half English miles through hard rock seemed a hopeless task, especially as it was impossible to provide the usual means of ventilation, by means of air shafts; but this problems has been solved, and time, we believe, will see the work brought to a successful termination. The estimated cost of the tunnel is 5,876,000 pounds, of which the French government are to pay two-thirds and the Italian government one-third. The works have already been in progress eight years; and one-half of the distance has been pierced, and it is expected that the work will be completed before the end of the year 1875.

" We halted for half-an-hour at the 'Hotel Royal' in the wretched-looking village of Lans-le-bourg, the houses in which, are little better than cabins and are occupied by persons, who are evidently steeped in poverty and ignorance. Their chief employment is that, of conveying merchandise over the mountain and occasionally assisting to clear the roads from snow. [They couldn't eat the hotel food] We went outside, and occupied the time by making a survey of the locality, which resulted in the discovery of wretchedness and misery, which I suppose could not be surpassed, even in the back slums of our large towns in England. Surely some one is responsible for this sad state of things and we trust that the day is not far distant when this evidently semi-barbarous people will be taught some of the lessons of civilization, and at the same time, some of the lessons of true religion also. Just as we were leaving the village of Lans-le-bourg we passed a large wooden cross, and a little beyond this the small chapel of St. Antoine, where travellers used to hear mass before adventuring into the pass. A priest is still obliged to say it there if required, but our party did not avail themselves of his services.

[A religious hospital and a

hospice strictly for the poor had

long been established up in the pass ...

as the exertion of the trip and snows presented significant risks to life and limb.

In June 1812, Pope Pius VII visited the area and his health was affected to the point that the last rites were administered to him.

Today the pass is not essential for transportation and it is closed for about 6 months per year in the winter and spring.]

as the exertion of the trip and snows presented significant risks to life and limb.

In June 1812, Pope Pius VII visited the area and his health was affected to the point that the last rites were administered to him.

Today the pass is not essential for transportation and it is closed for about 6 months per year in the winter and spring.]

The

'Yorkshireman'

is

following those green dots, from St. Michel to Susa.

" The highest point of the pass is 6780 feet above the level of the sea, but only 2000 feet above the valley of Lans-le-bourg, yet what an interminable distance it seemed by the zigzag course we took. Tired of turning corners, we got out and walked, not, however, following the road, but taking the sharp cross-cuts. As we walked along, we passed several houses of refuge, one of which we entered, and a most squalid and comfortless place it was. Twenty-three of these houses are placed at intervals along this pass, and the persons who occupy them live rent free, and have 15d. a day allowed - a miserable pittance, for which they are expected to keep the road clear from snow, to assist travellers who may have lost their way, and give warning of avalanches. These houses are often so buried in snow, that it is no uncommon thing for the women and children living in them, to be unable to step out of doors from autumn to spring.

Going up into the pass.

" Near to refuge No. 20, we came upon a line of railway in course of construction which is intended to cross the mountain instead of going through it. The line is laid down on the common road, but whether it will success is a matter for speculation, at present, it serves one useful purpose, that of protection to the diligence. The incline is of one yard in twelve, and a peculiarity of construction of this novel railway is a middle rail, the projecting parts of which are bitten or pressed by the horizontal driving wheels of engines constructed for this purposes. The engines will also have to work snow ploughs to clear the line of accumulations of snow. This singular line of railway was opened a few months ago, and the engineers who tested its safety, report most favourably, and predict that it will speedily supercede travelling by diligence over the Mont Cenis. We confess that we should prefer the latter mode rather than the first-named.

" We were passing from the genial warmth of the valley to the chilly regions of snow, and before we reached the summit of the pass, our conveyance had to take its course between walls of snow, which rose on either side to the height of several yards. ... The summit, or rather the highest part of the mountain which the road traverses is encircled with other mountains, objects of singular sublimity, one of which rises to the height of 18,000 feet, 6000 feet above the point we have at present attained.

In the Mont Cenis Pass.

[They later descended from the pass] " We were soon tearing along those awful zigzags, which conduct the road on its downward journey, on that ever to be remembered day, I cannot but wonder at the composure with which we travelled over so many miles, where precipices of fearful extent abounded - where rocks seemed impending over our heads, and a rushing torrent was careering along hundreds of feet below us - all these and the fearful speed at which the descent was made was certainly enough to make us feel somewhat nervous. ... The distance from the summit of the pass, to Susa, at the foot of the Alps, where our journey by diligence was to terminate, is 26 miles, which we accomplished in less than three hours.

" When we reached Susa, though we had been travelling sixteen hours with slight intermission, and nine of these hours we had been cooped up in a diligence, we scarcely felt a sense of fatigue, so much had the ever-changing scenery and the bracing air of the Alps kept mind and body in a state of joyous and pleasurable excitement. "

... end of ... A Yorkshireman's Trip to Rome in 1866

They spent nine hours

travelling by diligence from St. Michel, through the pass, to Susa.

This is a distance of 81 kilometres - '1 hour and 20 minutes' - by today's road.

This is a distance of 81 kilometres - '1 hour and 20 minutes' - by today's road.

Tunneling between Italy and France

1857-1870

from ... Light Science for Leisure Hours (1873)

"The Mont Cenis tunnel was

sanctioned by the Sardinian government in 1857 , and arrangements were

made for fixing the perforating machinery in the years 1858 and 1859.

But the work was not actually commenced until November 1860. The tunnel

which will be fully seven and a half miles in length was to be

completed in 25 years."

from ... Our Iron Roads (1883)

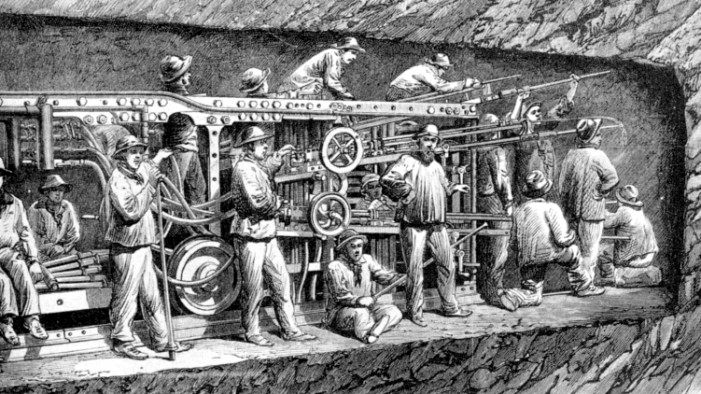

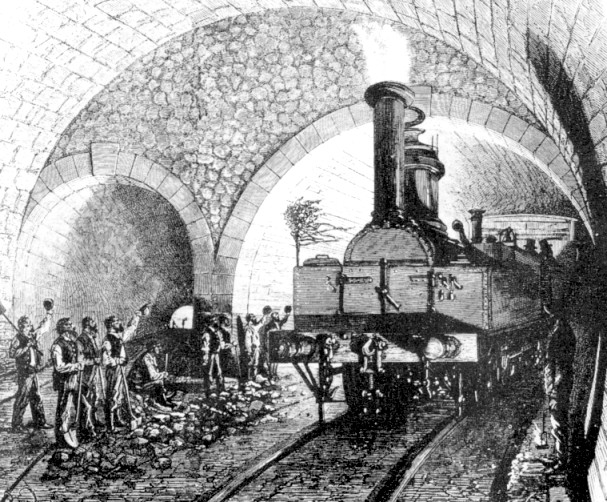

" The agencies by which the actual excavation of the tunnel was accomplished were remarkable in many respects, and especially with regard to perforating machines, and the power employed to bring them into operation.

" The use of steam would have caused smoke and vapour, which would have been intolerable in a long closed gallery. The power of mountain torrents was therefore brought into service; and, by means of water-wheels, air was compressed into tubes which drove the perforating engines that pierced into the rock the holes necessary for blasting, and it also, after the explosion, cleared the foul atmosphere away.

" The compressing engines were outside the tunnel, the air from them being driven along flexible pipes; and the perforating engine with its nine or ten perforators itself rested upon a tramway, so that it could be moved forwards or backwards as required. The perforators were similar in appearance to large gun barrels, and out of each of them a boring bar, or jumper by the admission behind it of a blast of compressed air, was rapidly shot at the rock; the return stroke being make by similar means. At the end of about three-quarters of an hour each perforator had pierced a hole from two feet to two feet six inches in depth into the hard calcareous and crystallized schist traversed by quartz. Another ten holes were then commenced; and so on till about eighty had been made. The perforating machine was now drawn backwards on its truck, and sheltered behind two massive doors. Miners then advanced, charged the holes, adjusted the matches, lit them, retired behind folding doors which were at once closed, and the explosion followed. Air was injected, and gangs of men proceeded to clear the debris into little wagons that ran on a tram line beside the main tramway.

" These three operations occupied together from ten to fourteen hours, and it is easy with these data to calculate the rate at which the work advanced."

end of ... Our Iron Roads (1883)

from ... Our Iron Roads (1883)

" The agencies by which the actual excavation of the tunnel was accomplished were remarkable in many respects, and especially with regard to perforating machines, and the power employed to bring them into operation.

" The use of steam would have caused smoke and vapour, which would have been intolerable in a long closed gallery. The power of mountain torrents was therefore brought into service; and, by means of water-wheels, air was compressed into tubes which drove the perforating engines that pierced into the rock the holes necessary for blasting, and it also, after the explosion, cleared the foul atmosphere away.

" The compressing engines were outside the tunnel, the air from them being driven along flexible pipes; and the perforating engine with its nine or ten perforators itself rested upon a tramway, so that it could be moved forwards or backwards as required. The perforators were similar in appearance to large gun barrels, and out of each of them a boring bar, or jumper by the admission behind it of a blast of compressed air, was rapidly shot at the rock; the return stroke being make by similar means. At the end of about three-quarters of an hour each perforator had pierced a hole from two feet to two feet six inches in depth into the hard calcareous and crystallized schist traversed by quartz. Another ten holes were then commenced; and so on till about eighty had been made. The perforating machine was now drawn backwards on its truck, and sheltered behind two massive doors. Miners then advanced, charged the holes, adjusted the matches, lit them, retired behind folding doors which were at once closed, and the explosion followed. Air was injected, and gangs of men proceeded to clear the debris into little wagons that ran on a tram line beside the main tramway.

" These three operations occupied together from ten to fourteen hours, and it is easy with these data to calculate the rate at which the work advanced."

end of ... Our Iron Roads (1883)

The perforating machine designed and perfected by Sommellier and others.

Two of these machines were working toward each other - from opposite ends of the tunnel.

They were driven by compressed air generated by falling water at the portals of the tunnel.

From 'The Mont Cenis Tunnel - Its construction and probable consequences' (1873)

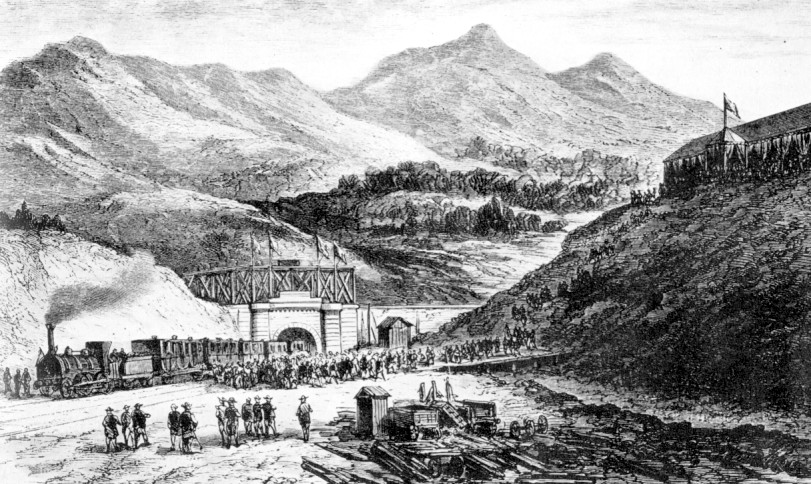

"In 1871 several things happened. The Papal temporal power ceased, Italy became a united kingdom,

and the first train passed through the great Alpine tunnel to the west of the Mont Cenis Pass.

The old Sardinian State tank engine carries a bouquet from France on her right-hand tank, an unusual tribute from sticky neighbours!"

[Top hats of dignitaries riding on the engine's footplate can be seen.]

"The first train to arrive from Italy through the Mont Cenis Tunnel. There was an inauguration banquet for the guests"

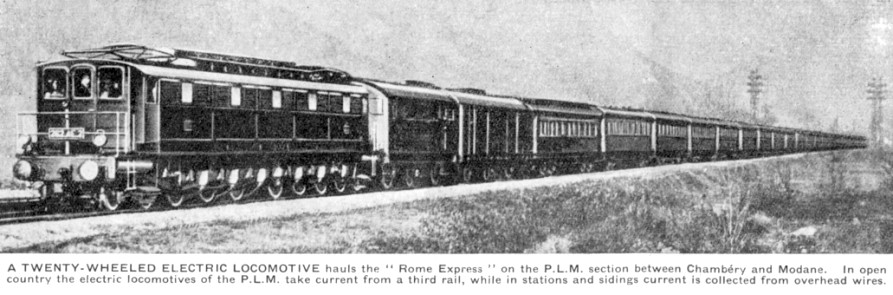

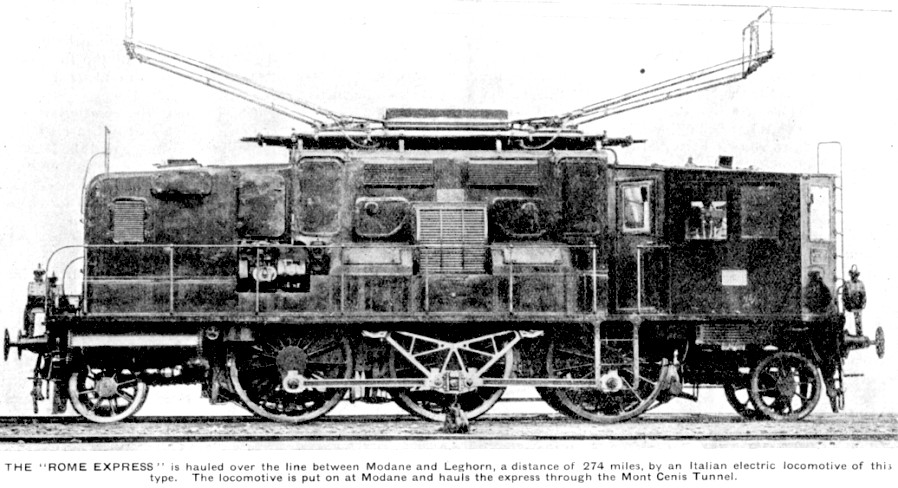

The "Rome Express"

from "Railway Wonders of the World" periodical, 1935

from "Railway Wonders of the World" periodical, 1935

" It is not such a veteran as its sister train the 'Orient Express' for it did not begin regular running until November 15, 1897. At first the 'Rome Express' ran only during the winter months, and then but once a week, the Italian summer climate not being agreeable to the majority of Northern Europeans, for whom the train was mainly operated ...

" At the time of its inauguration, the 'Rome Express' left Calais at 12:49 mid-day and arrived at Rome at 10:25 on the evening of the following day. In view of the general operating conditions of the period, especially in Italy, this was remarkably good running. The cars contained four berths in each compartment, and in this way were little superior to the original rolling-stock on the 'Orient Express'. Gas lighting and steam heating were incorporated. The exterior of the old train was handsome enough, though some of the old-fashioned Continental locomotives which hauled it at that time were of rather alarming appearance.

" The four-berth compartments gave way to the double berth type in 1901, and single-berth compartments, generally similar to those on British trains, but convertible for day use, appeared in 1923 ...

[The 1930s version of the train stops at Chambery, France at 4 AM] " ... At Chambery a change-over to electric traction is made, and we shall be far down in Italy before a familiar puffing comes once more from the head of the train. The electric locomotives of the PLM [Compagnie des chemins de fer de Paris a Lyon et a la Mediterranee] are peculiar. They collect current from a third rail at the side of the running rails while in the open country, but in the stations and sidings overhead wires are provided, the locomotives being fitted with pantograph bows as well as collector shoes. This is to render the movements of shunters and station porters in the yards and sidings less dangerous. In Italy there is a different system of electrification, and it is possible to study the two systems side by side in the station of Modane, on the Italian frontier.

" From Chambery onwards to Modane, through St. Jean de Maurienne, the only intermediate stop, the train passes through magnificent mountain scenery. If the passenger is travelling at the right time of year, and if the weather is fortunate, he will be treated to a sunrise effect not easily forgotten. Most of us, however, are not fond of early rising, and many sunrises come and go without being appreciated. Not infrequently it is a night train, roaring up through the morning mists, that gives the best view of the most beautiful of all natural phenomena. A fine effect which has been lost with the coming of electric traction over the mountain section, was that made by the columns of snowy-white vapour which used to rise high into the morning air from the locomotives at either end of the train as it climbed steadily up to the Mont Cenis Tunnel. The smuts and coal-dust from those labouring engines used to be rather formidable, and settled in thick layers on the carriage window-sills. But there was nothing to beat the grandeur of the effect as the engines crept up the valley with their high smoke-plumes above them.

" Modane, where we leave the PLM, is a rather interesting place. It might be in either France or Italy, and its name might belong to either language. It is in France, in the extreme south of the department of Savoy, through whose mountains the 'Rome Express' has been passing since it left the country preceding Aix-les-Bains. Modane is a single straggling Alpine township shut in, apparently on all sides, by high mountains. The 'Rome Express' reaches it at 5:45 AM, roughly five hours and twenty minutes after leaving Dijon, 235 miles away. This is remarkably good running when we consider the climbing which has to be done.

" At Modane most trains undergo official examination by the Italian Customs officials and frontier police, but in the present instance this is carried out on the train itself. Soon we shall be familiar with the black-shirted military railway police, who are to found on the trains, stations, and tracks all over Italy.

" The train waits at Modane for half an hour, but as Italy sets her clocks by Central European time, our watches point to 7:15 (if we have put them on properly) when the 'Rome Express' glides out to cross the frontier behind an electric locomotive belong to the Italian State Railways. The Italian electric locomotives work on the three-phase system, consequently double collector bows are mounted on the cab roofs, and there are two conductor wires overhead instead of one for each track. Before the great Mont Cenis Tunnel was opened in 1871, a 3 ft 8 in gauge line, constructed on the principle invented by Mr. J B Fell, carried passengers, goods, and mails right over the Mont Cenis Pass, topping a summit nearly 7000 feet above sea level. This was long before the 'Rome Express' started running ; but it is worth recalling.

" After leaving Modane, and before entering the Mont Cenis Tunnel, the line rounds a complete horse-shoe curve, rising all the way. The Mont Cenis is the oldest of the great Alpine tunnels, and we wonder at the perseverance of its builders all the more when we realize that the whole of its length of 8 miles 832 yards was bored without the aid of pneumatic rock-drills or any of the modern appliances which are now considered essential to tunnel building. It is feared that Mark Twain when he went to Turin was not properly reverent, for he said that he travelled by a railway profusely decorated with tunnels, and that as he had omitted to bring a lantern along with him, he missed all the scenery.

" The 'Rome Express' tops its Alpine summit-level as it passes through the Mont Cenis Tunnel. As we fell the speed gradually increases, we realize that we are beginning to run down into Italy. At the Italian end of the tunnel the train passes through a gallery in the face of the mountain before finally emerging into the open. Looking back, we obtain an unforgettable view of the great Alpine mountain mass, under which the train has passed towering into the sky. At most times of the year it is thickly cloaked with snow. Mont Cenis Pass is 6860 feet high, the summit being in Italy. It is, however, somewhat east of the wall of rock under which the railway finds its way for nearly eight and a half miles."

end of 'The Rome Express' (1935)

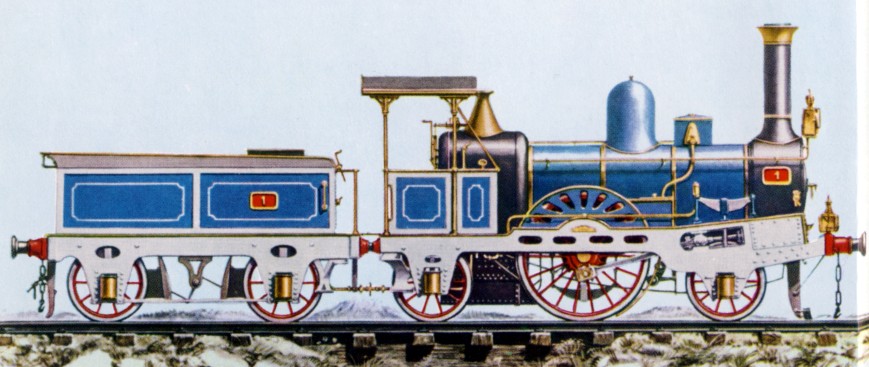

A 'Canadian Connection' with Italian Railways ?

The particular locomotive illustrated above (drawn from a 'locomotive plan' book)

was built by Peto, Brassey and Betts at the 'Canada Works', Birkenhead, England.

It was used by the 'Roman Railways from 1863 for about 20 years'.

It was while researching this page, that I found this interesting illustration.

I have never seen an image of the 'first locomotives' in their 'original condition' as used on the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada.

About 13 were built 1854-56 at Birkenhead for the GTR - all with the same 2-2-2 wheel arrangement.

Notice the tiny, slanted piston and the thin driving rod.

A sanding pipe is provided to improve the driving wheel's traction, particularly when starting.

Manual brakes are operative on the tender's wheels.

The Canadian Grand Trunk Railway 2-2-2 locomotives of this type were rebuilt with 4-2-2 wheel arrangements in 1855-56.

They were later converted to the very common 4-4-0 wheel arrangement, then disposed of by 1874.

[4-4-0 ... pronounced 'four four oh' ... i.e. 4 pilot wheels, 4 'drivers', 0 trailing wheels supporting the firebox/boiler]

Grand Trunk Railway Number 70 of the original Birkenhead group,

was rebuilt as a 4-4-0 , and later sold to the Carillon and Grenville Railway ...

the latter was an isolated 'portage railway' on the Ottawa River.

Back to Sitemap