Schreiber and White River

Much has been written about Fort William, Port Arthur

and the current city of Thunder Bay. The Schreiber to Thunder Bay

run over the Nipigon Subdivision was never as interesting to me as

the "East End". My favourite trips were between Schreiber and White

River through the wilderness of the Heron Bay Subdivision.

On the highway

signs of the time, Schreiber had a population of 2000 and White River

had a population of 1200. With further streamlining of railway operations

in the area, both of these towns are a little less crowded than they

were in the late 1970s.

How did these little railway towns start?

In the late 1800s, several surveys were run through

the country north of Lake Superior, as politicians were musing

about an all Canadian railway route to unite 'the east' with the

tiny colony of British Columbia. The proposed railway, and settlement

of the land along its route, would help ensure that the traditional

Hudson's Bay Company lands and the rest of 'the west' did not become

part of the United States.

Some very interesting books were written at this time

about how to organize railway surveying expeditions into the wild.

Pack horses, dried food (hunting was useless as a source of food),

simple optical and analog instruments, and significant backwoods skills to survive

and survey in the middle of nowhere were required. There were no warm

clothes and tents made out of synthetic fibres, no cell phones, no GPS,

no police, no hospitals, no doctors. There was only the occasional fur

trading post to provide any needed help. Serious injury or starvation

could change your plans for the rest of your life pretty quickly.

The job was to locate a nearly flat railway line as

economically as possible. This was difficult because there were

only hundreds of miles of rounded granite mountains, lakes, and swamps

to build through. The best steam locomotives of the day could run

about 125 miles before they needed more coal and fresh crews. So,

along the north shore of Lake Superior, the railway builders needed to

establish at least two townsites (called "division points") which met

the following criteria:

- Flat land on which to build long railway yard tracks - to receive

the trains and switch their cars.

- Adequate flat space for stations, locomotive and car shops, coaling

towers, worker housing, 'rest & exercise' stockyards, and community buildings.

- Abundant fresh water for locomotives and people.

- These locations had to be at roughly 125 mile intervals from the

established settlement of Fort William and other planned railway

terminals farther to the east.

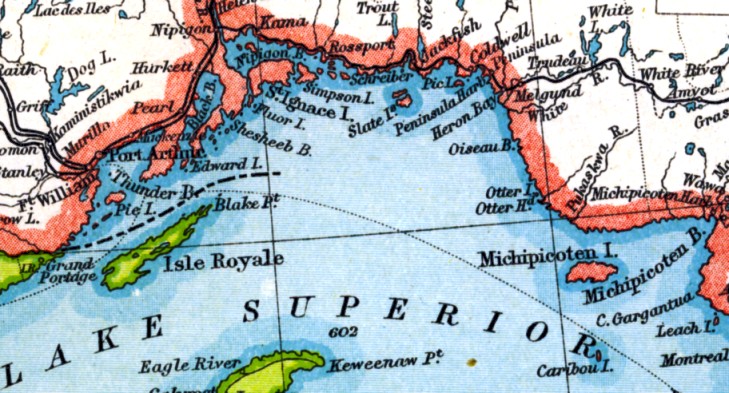

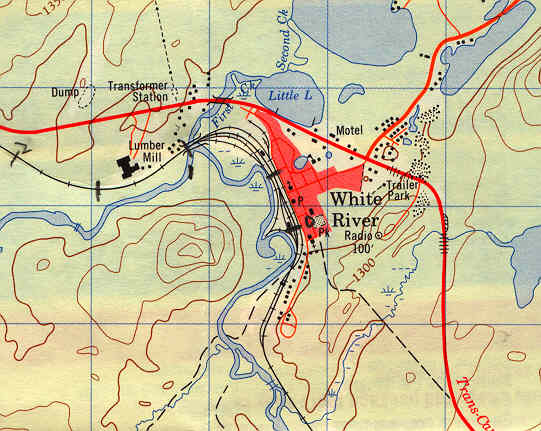

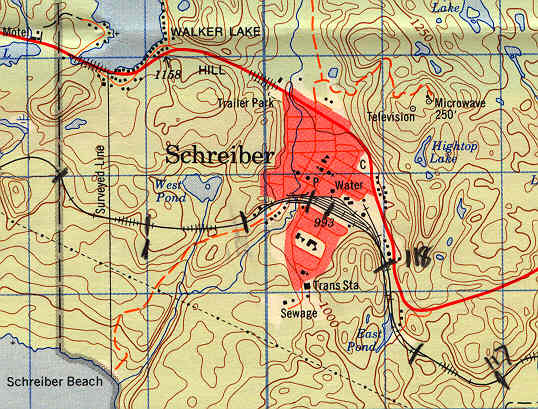

So Fort William; Schreiber (centre of map); and White

River (at right) became the "railway towns" for this region.

Building along the shore of Lake Superior

in 1883-1885 was more effective than building inland:

- Steam-powered ships could bring in rails, additional workers,

food and supplies between winter freeze-ups.

- Construction was completed more quickly because shoreline building

at many points could be started in both directions.

- Given the difficulty of blasting through granite, inland construction

done only from the "end of track" would have probably

run afoul of the company's guarantees to the government to complete

the line on schedule.

- However, powerful Lake Superior storms quickly washed away the

broken granite "fills" for the roadbed along the shore if they weren't

built carefully.

White River: Home away from home

My eastern 'objective terminal' in 1977.

Dr. W.G. Houston was White River's physician from 1933

until his death in 1966. In 1985, the centennial of White River and

the railway line, his wife Mary Houston put together a wonderful, comprehensive

pictorial history of White River. Using old photographs shared by White

River's citizens, it shows all aspects of community life in the little

railway town from its very beginnings. Most of the following information

on White River's development comes from her book.

Mary Houston passed away in December 2005 at the age of 86 having lived all

of her life in White River.

There are at least two points she would want me to bring to your attention.

First of all, CPR records show it was NEVER officially named

'Snowdrift' - always White River. In 1937, a record 13.1 feet of snow

fell there.

More importantly, White River was long advertised as 'the

coldest spot in Canada' at -72 degrees Fahrenheit. This is not correct because that reading came from a shattered thermometer. The lowest

temperature recorded was -61.2 degrees F on January 23, 1935 and this

is proven in her book through the use of official weather records.

I'd like to add that the title should be:

'The coldest spot

in Canada ... which provided daily telegraph reports of its temperatures ...

back then ... which were regularly published in newspapers '

This

doesn't fit on a souvenir T-shirt, though.

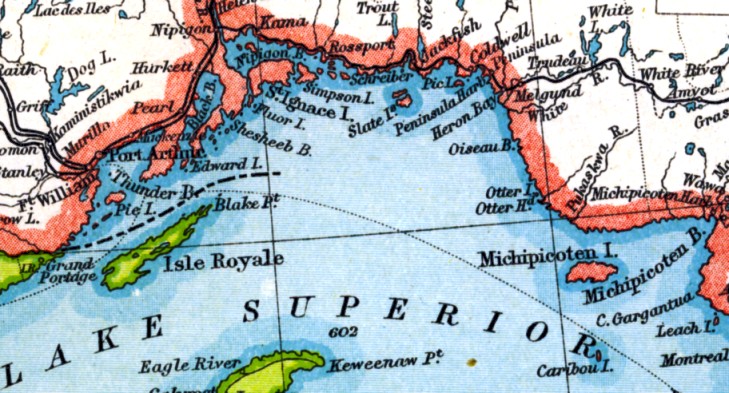

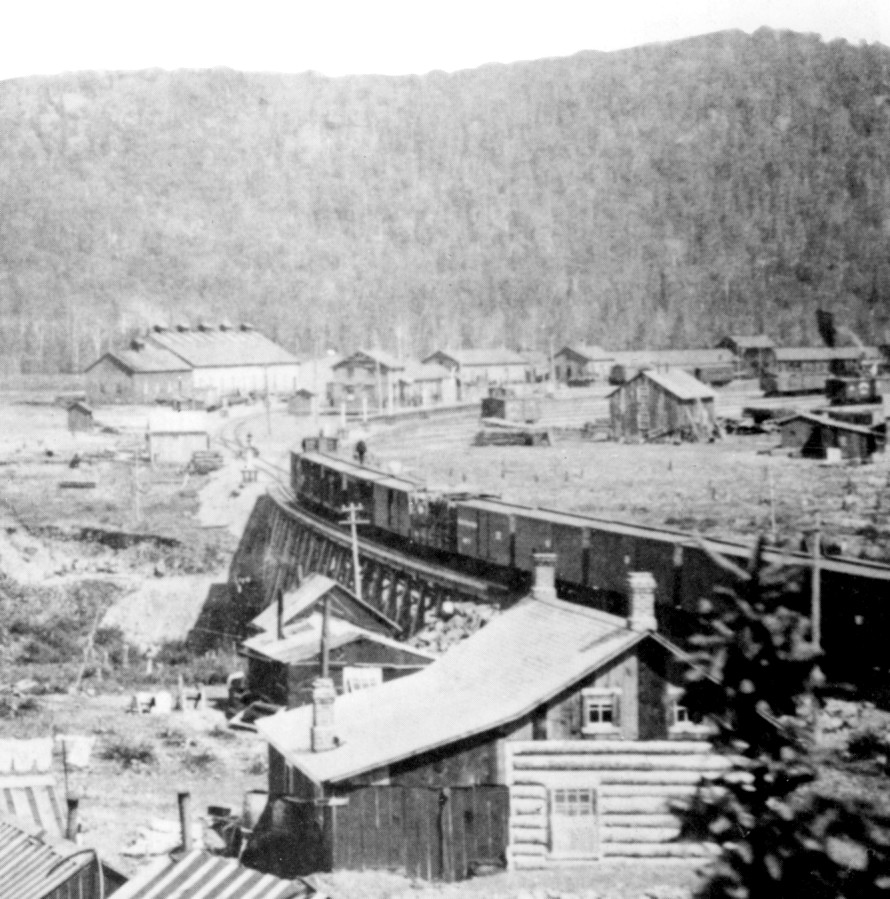

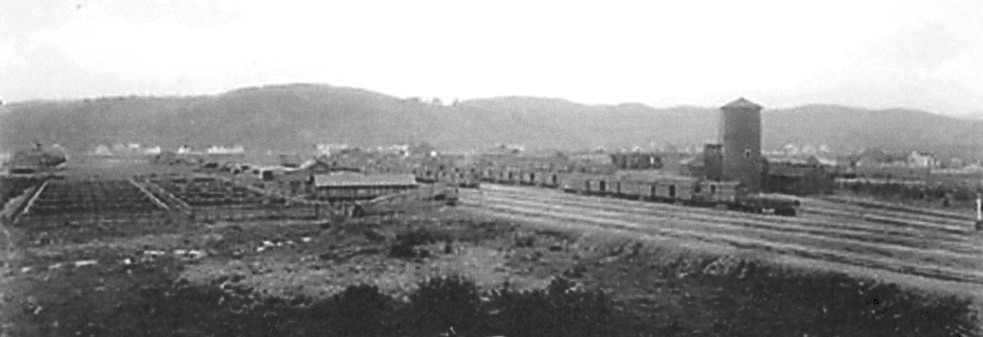

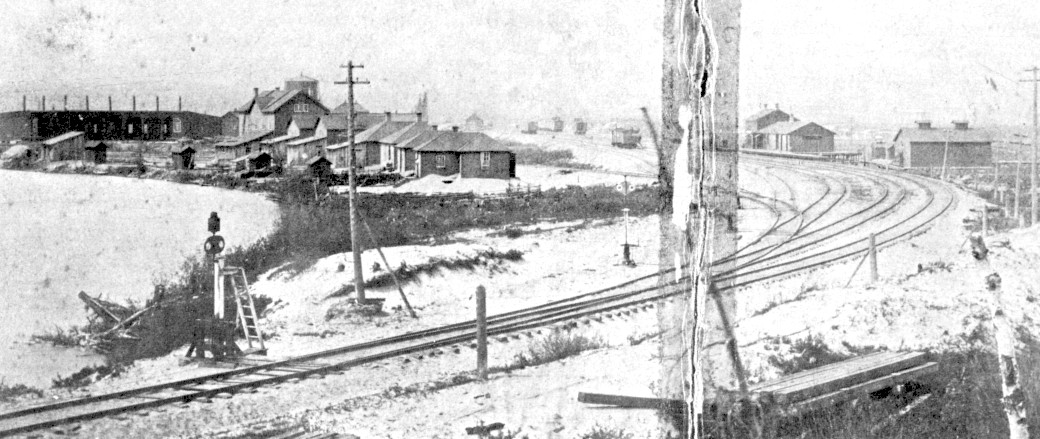

This early photograph is from "White River - 100 Years, Pictorial History" by Mary Houston.

This early photograph is from "White River - 100 Years, Pictorial History" by Mary Houston.

The caption reads:

"First CPR company houses and lodging house built on the river bank with view of rail yard and station.

Later these houses were moved across the tracks to the east end of town which became known as 'Little England'

Photo: Courtesy M. Leadbeater"

The photo may be from around 1890.

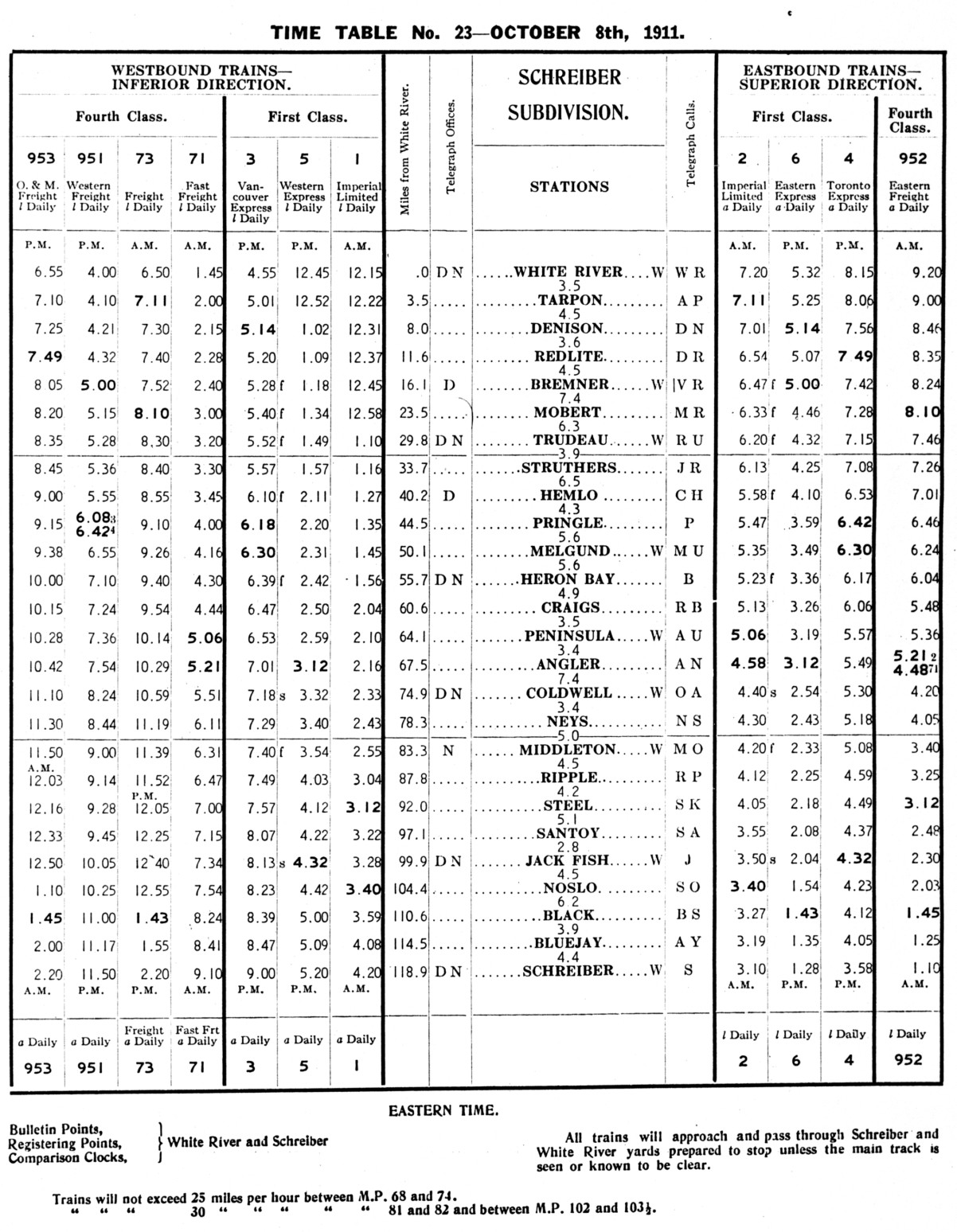

Then, it included the

following Subdivisions:

Cartier to Chapleau - Chapleau Sub - 137.4 mi

Chapleau to White River - White River Sub - 131.8 mi

White River to Schreiber - Schreiber Sub - 118.9 mi

Schreiber to near Port Arthur - Nipigon Sub - 128.5 mi

|

The Chief Train Dispatcher and six train dispatchers were at White River along with the Division Superintendent.

There was an Assistant Superintendent at Chapleau and a Trainmaster at Schreiber.

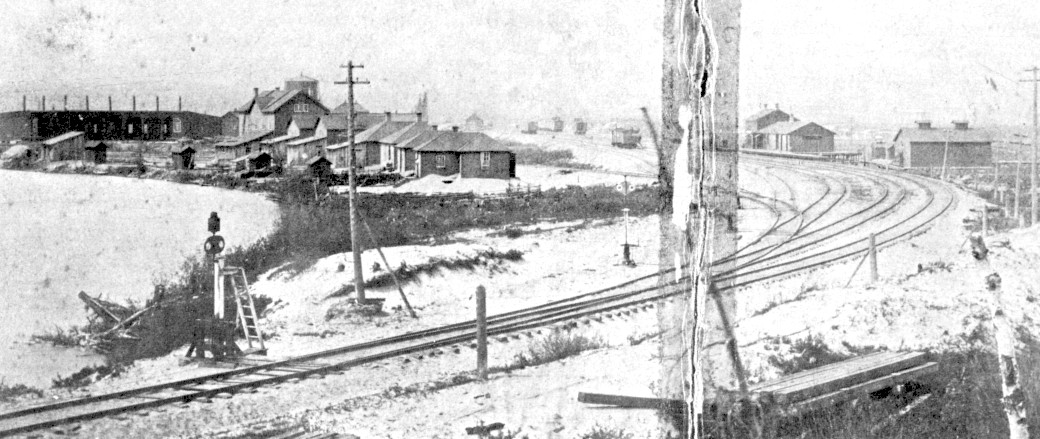

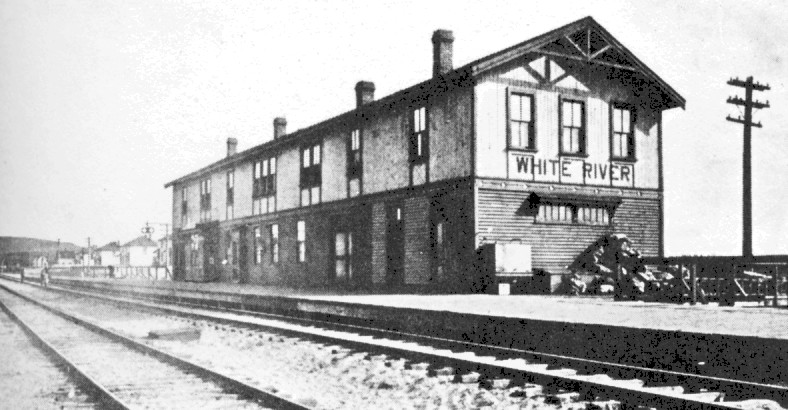

The enlarged White River station photographed in 1907.

Division offices and the dispatchers were upstairs.

The train order and register office was at the far end.

District No. 1

of the Lake Superior Division ran from Chalk River to Cartier, both in

Ontario, and included the line to Sault Ste Marie and the US.

White River was probably chosen as the administrative

centre because it was in the geographical centre of District No 2.

However, The White River - which you can see in the first photo above - has a history of

sometimes flooding during the spring thaw. It seems likely that this

problem and the lack of physical space to expand caused the Division

Headquarters to move to Schreiber.

Schreiber received a fancy new

station around 1924 and this was likely co-incident with the change ... or not ... definitely one or the other.

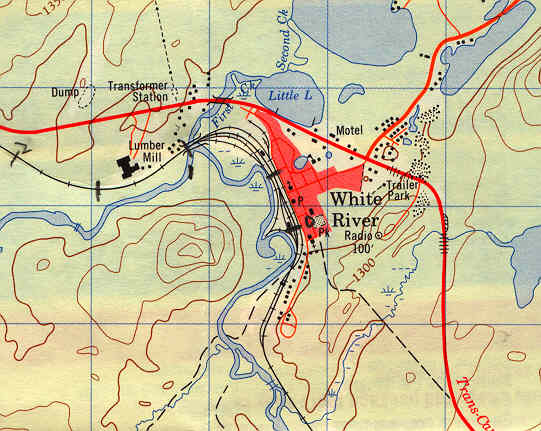

In 1977, White River was where we waited for our turn to work the

next train back home to Schreiber. As you can tell, the land quite

flat ... and the meandering White River flows right by the yard

and shops. In May 1936 and May 1979, the White River flooded the town.

In the earlier days of White River, the CPR built the following:

- Locomotive and car shops and a passenger station with business

offices.

- A coaling facility and water tank.

- Worker housing and a CPR rooming house.

- A building for storage of block ice cut in the winter - which

was used for freight car ice bunker refilling, and likely some local refrigeration during the summer.

- Stock pens to feed and exercise entire trains of live cattle coming

east for slaughter (before reliable refrigeration and the ability

to freeze meat for transport). Other livestock, such as sheep and horses, was also sent across the country.

In the late 1970s, loaded stock cars were still coming east,

marshalled at the headend of some of our freights. However, the stock

pens were demolished in 1976 because the Winnipeg to Toronto journey

could be made without cattle rest stops within the federally required

40 hour period. The pens were located where it says "First Ck" on the

map, by Little Lake.

When in White River, stay at ...

White River once had a YMCA which served as a pleasant centre for

townspeople to meet socially and a place for visitors to stay. Its main

function was providing rest facilities for off duty crews and junior

railway personnel from out of town. It burned down in the 1950s. On the

same location, CP built a bunkhouse where we slept and/or waited until

our trains arrived. It is located at the bottom tip of the red shaded

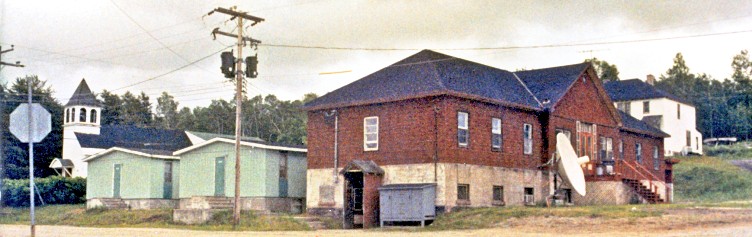

area of the map.

The original

CPR bunkhouse is the brown building, and we slept behind in the green

"portables".

In the Old Days ...

Before the 1960s (approximately) when particular vans (cabooses) were

assigned to particular conductors ... the conductor and the two

brakemen slept on wooden benches - with mattresses and bedding - in the van when off duty and away from

home. But the engine crew - the engineer and fireman - slept in the

brown building above when off duty and away from home.

Consider a single typical eastbound freight running from Winnipeg to Montreal ...

Ten (5 + 5) crew members are required to move it from Schreiber to Chapleau.

At White River, the Schreiber crew rests and will return home to Schreiber on some other train.

At White River, a rested Chapleau crew will take over this particular freight, thus returning home to Chapleau.

Freight Train runs ... Schreiber to White River

Arriving operating crew lives in Schreiber

|

Freight Train runs ... White River to Chapleau

Departing operating crew lives in Chapleau

|

Engine crew sleeps in White River bunkhouse

Engineer

Fireman

|

Engine crew sleeps in White River bunkhouse

Engineer

Fireman |

Train crew sleeps in van

Headend brakeman (rides on engine)

Tailend brakeman

Conductor

|

Train crew sleeps in van

Headend brakeman (rides on engine)

Tailend brakeman

Conductor |

Remember this was typical in the days of steam before 1960.

In large terminals - not necessarily White River - conductors put

special markers on top of their van cupolas to make their van easy to

spot.

In large terminals - not necessarily White River - conductors put

special markers on top of their van cupolas to make their van easy to

spot.

... like markers on auto radio aerials in crowded parking lots today.

Inside a steam-era caboose on an American road with the train crew - washing dishes.

Inside a steam-era caboose on an American road with the train crew - washing dishes.

Later in history ...

when the van was left attached to the through freight train

and not assigned to the conductor living in Schreiber or Chapleau ...

the conductors and brakeman bunked in with the engine crew at the enlarged bunkhouse.

A big happy family.

Getting back to the White River bunkhouse in 1977 ...

Each room had its own desk, chair and bed. The place had

showers, cooking facilities and satellite TV.

On arrival, you simply wrote your name beside any room number on the chalkboard where the 'name space' was blank.

When the crew callers came for us, they had four names (diesel era) for

the ordered train. They looked for your name ... and came to your room

if you weren't in the 'common room' watching the Peter Gzowski talk

show on CBC TV.

At your room, the crew caller would:

- Go to your room and bang on the door.

- Immediately open the door.

- Immediately turn on the light and walk right in.

- Say something like "Gagnon, extra west at 0300".

- Squint at you for a second to satisfy themselves you were past

the point of going back to sleep.

- Leave, closing the door and leaving the light on.

You then got ready and reported to the station to take your

westbound freight train back to Schreiber at 3 AM.

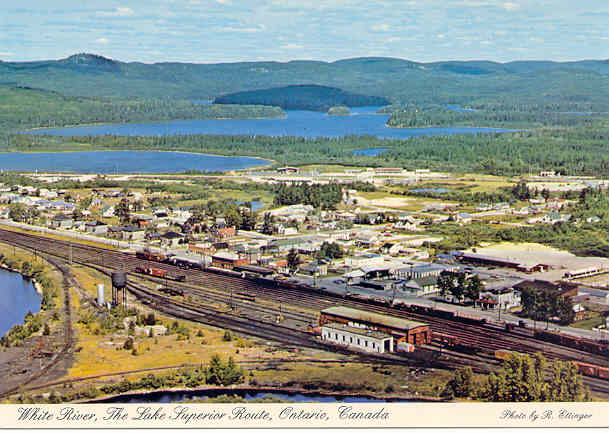

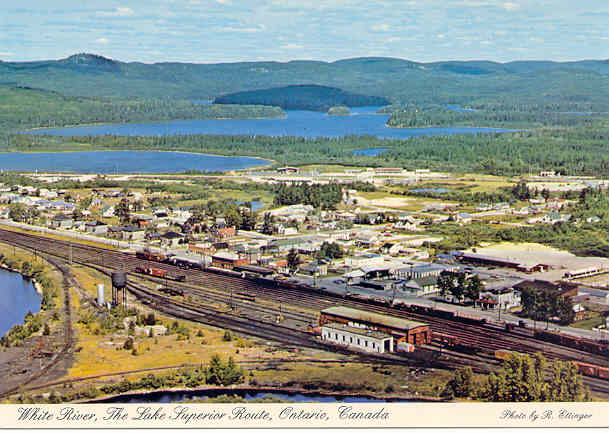

Here is White River in the 1970s. The Trans-Canada Highway

runs across the top of the town on this postcard and you can see

the souvenir shops and services which sprang up in the 1960s to sell

those "coldest spot in Canada" T-shirts to tourists. You can also imagine

that when The White River (lower left and bottom) flooded there would

be wet basements all around.

Looking back from the dome car on the westbound

Canadian in 1984, you can see the station and offices to the

left of our track, then the yard, and the water and fuel facilities

to the right. At this point, White River was losing its ability to repair

locomotives and cars to larger facilities such as Thunder Bay.

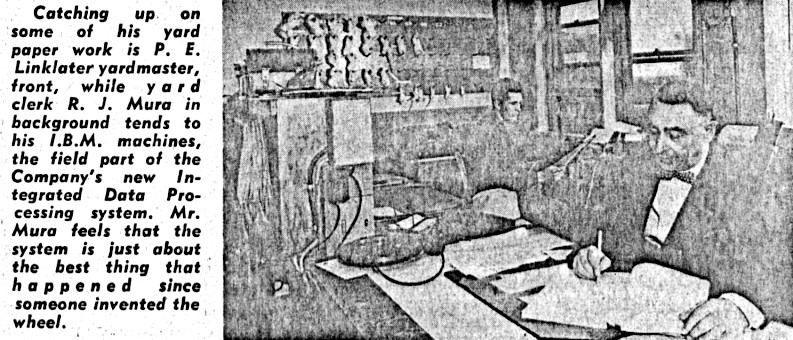

In the White River yard office

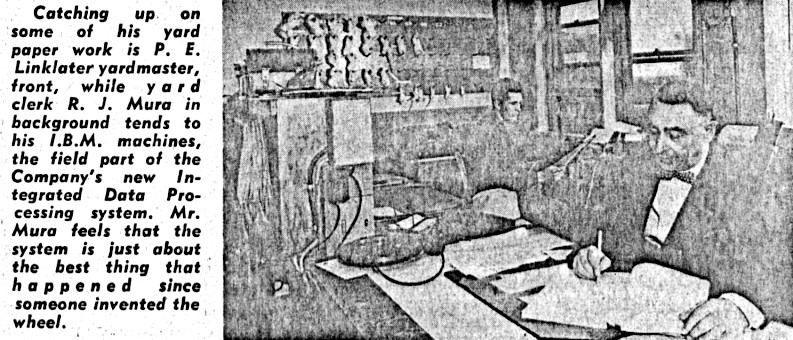

In researching this piece, I was reminded of one of the

nicest experiences I had during my Lake Superior effort. For a short

while I worked as an "intern" at the White River yard office with the

night shift machine operator Bob Mura. He taught me how to work on the

old IBM teletypes - which produced a punched tape record of a train's

cars (a train consist). These long tapes were wrapped in a figure-eight

motion around your thumb and pinkie finger and hung up on pegs to be

fed into the machines for later transmission to Montreal to update their

car control computer. Today, you could probably record the data from

a room full of these primitive "storage media" on a single CD-ROM.

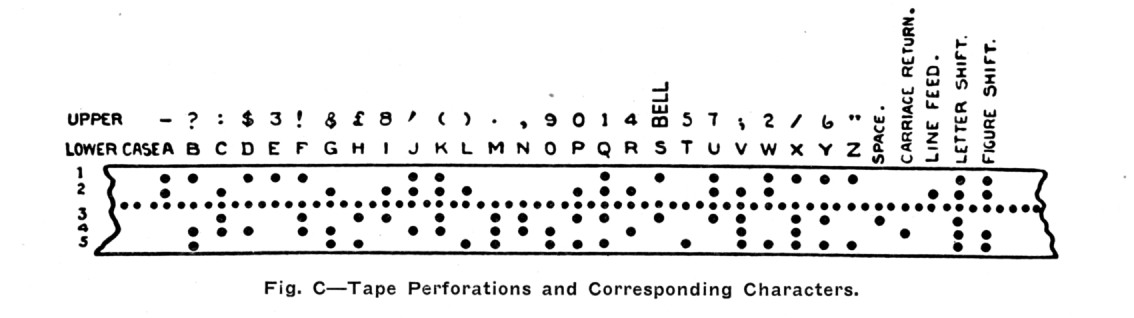

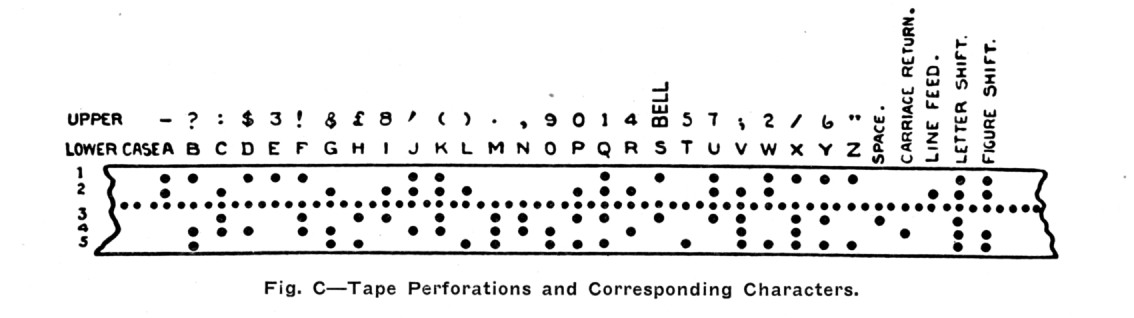

Quoting a 1938 reference: "The usual speed of transmitters on railroad circuits is about 6 pulses per second.

Quoting a 1938 reference: "The usual speed of transmitters on railroad circuits is about 6 pulses per second.

This means that about 360 characters will be sent per minute."

(This 6 Hertz 'processor speed' sounds about right as I remember the machines)

One cold dark winter night, the powerful White River yard office radio crackled

with an engineer's call that their freight had just put fifty ("five

nought") cars in the bush to the east of White River. "Man, that's

railroading!!" said Bob.

Whenever there was a derailment, the trains would all cram

into terminals like White River to wait for hours or days until the

line could be reopened. Stranded train crews at the bunkhouse were sometimes

called for duty just to refuel the diesel-powered refrigeration units

of similarly stranded semi-trailers and shipping containers travelling

on flatcars.

Eddie Doyon's retirement at White River station.

Photo courtesy of Jason Cottom

Edna & Ed Doyon, R.J. Mura (dark glasses), Bill Card, Charlie Linklater,

Ernie Gionet, Tommy Hogan, Mac McLeod, Irvin Baziuk, Bob Roffey.

I am very grateful to Bob Mura's grandson for reading my memories

of White River, contacting me, and sending this photograph (April 2009).

The event shown dates back about 30 years and I recognize many of the faces.

I think the facial expressions here communicate a lot to you about my experiences in White River.

Bob Mura taught me how to use the IBM teletypes during the night shifts.

Assistant Superintendent Tees had suggested I could stay at the bunkhouse during the training.

I was preparing for a summer relief vacancy at a station to the east.

Bob was a good patient teacher ...

even when the Montreal computer repeatedly

rejected the train consist tapes I had typed off-line

and then submitted on a live machine.

He explained to me that the running trades required a 'different kind of

cat' ...

and that life on the road could be very demanding, with significant

stress and time away from home.

In our short time together, he certainly made me feel much better about some decisions I had made.

Eddie's Retirement wasn't the only 'end of career event' which Bob attended.

I departed White River (and CP Rail) for eastern Ontario on Train Number 2 in the middle of the night.

It was a clear and cold, and the patches of snow remaining on the hard asphalt platform squeaked underfoot.

Bob came out with me in his shirt-sleeves to see me off ... and waited there with the station lights behind him as I boarded.

I'll always remember his friendliness and support during those last few days.

* * *

from L.C. Gagnon

A 2009 scan of a just-discovered 1980 photocopy of a 1958 CPR Spanner magazine.

You can see the figure-8 wound tape consists - usually one for each train - on the varnished wood pegboard.

And there's Bob at the centre of the photograph.

[After seeing this photo, Jason Cottom advised me that P.E. Linklater is R.J. Mura's father-in-law ...

Many railroaders had nicknames and Yardmaster Linklater was known as 'Hot Cakes'.

If you are doing the math at home ... this is a photo of Jason's Grandfather and Great Grandfather]

"Clarence Cottom beside engine 2228 that held the punch bowl for his retirement party.

Photo: Courtesy J. Dillabough"

This is one of my favourite photos from Mary Houston's book

and I have previously posted it as part of other White River pages.

It shows Jason's other grandfather.

Sometimes cakes or other mementos were decorated with the locomotive number of a retiree's last run.

Here is a 1932 snapshot of another Angus Shops built engine of the same class as Clarence Cottom's 'last run'.

"Flood - May, 1936. Clem Cowan and Mary Whent paddling on Winnipeg Street"

It must have been quite a project to pull together, safeguard, sort, select, caption, reproduce, and return

a collection of photos to represent White River's 100 years of history in 1985.

Mary Houston (shown here as a teenager) and the citizens of White River

have made a great contribution to the understanding of

'the human experience' of railroading and living together

in a small close-knit CPR community from its earliest days.

Schreiber: Home

My 'home terminal' in 1977

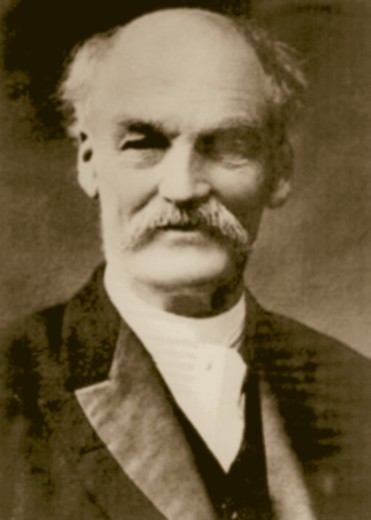

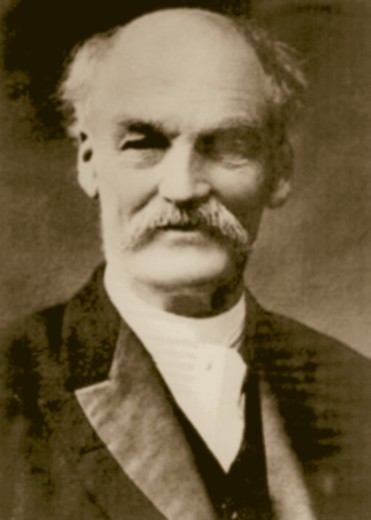

In Schreiber, there is an Ontario historic plaque which reads:

Sir Collingwood Schreiber 1831-1918

"This community, originally known as Isbester's Landing, was

named in 1885 after Collingwood G. Schreiber. Born at Bradwell Lodge,

near Colchester, England, Schreiber emigrated to Canada West in 1852.

His training in England as a civil engineer enabled him to play a significant

role as a field surveyor and administrator in Canada's era of railway expansion.

Schreiber was associated with the Northern Railway between 1860-1864 and

the International between 1868-1875 before succeeding Sandford Fleming in

1880 as Engineer-in-Chief of the Canadian Pacific. Schreiber retained this

position until 1892 when he became deputy minister of the federal Department

of Railways and Canals. He was knighted in 1916 for his public services."

Photo from Rolly Martin

Photo from Rolly Martin

James Isbester after whom Isbester's Landing (later 'Schreiber') was named.

He was a contractor for key parts of the Lake Superior line -

particularly along the granite shoreline east of Schreiber.

James Isbester

1840-1899

(dates approximate)

- Born: Orkney Islands and came to Canada as a youngster when his family settled near Woodstock.

- As a young man, worked as a mechanical engineer on the Great Western Railway (Canada).

- Began contracting experience in 1869, building a portion of the Rimouski Bridge under Alexander Macdonald.

- Subcontractor on the Intercolonial Railway.

- Built Section B of the CPR in partnership with Manning and Macdonald - along the north shore of Lake Superior.

- Contracted with R.G. Reid (of the Newfoundland Railway) on the Cape Breton extension of the Intercolonial Railway.

- Completed a contract on the Crow's Nest Pass in the spring of 1899.

- Died of complications from diabetes during a trip to inspect a contract in the Rainy River district.

- 'Ardent Conservative', Presbyterian, and 'warm personal friend' of Sir John A. Macdonald.

From the text of an obituary supplied by Brian Westhouse, December 2005

|

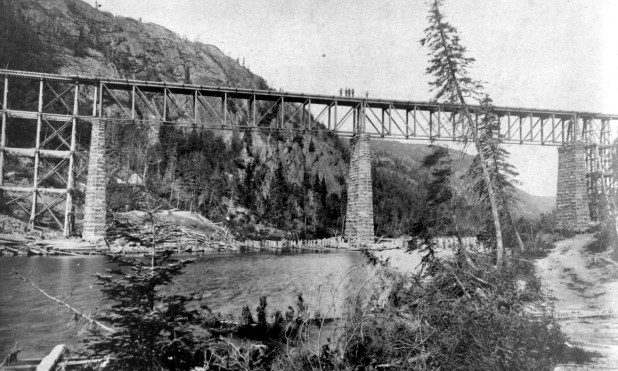

It is quite possible that Isbester's contract included this bridge.

The Little Pic River bridge, mileage 81 Heron Bay Sub,

has 'always' had a 30mph slow order due to grades and curvature.

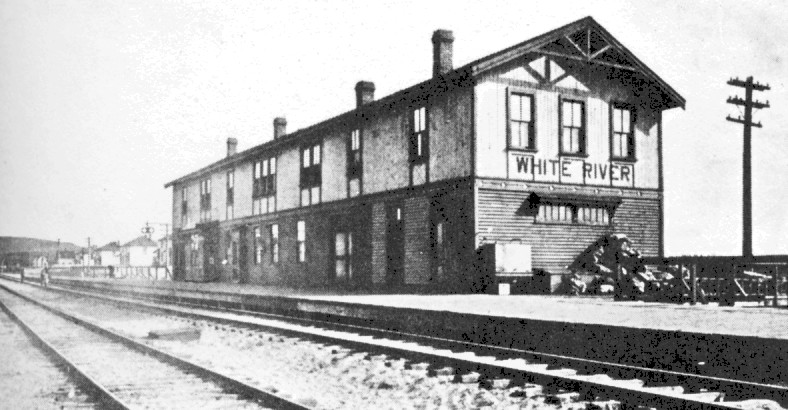

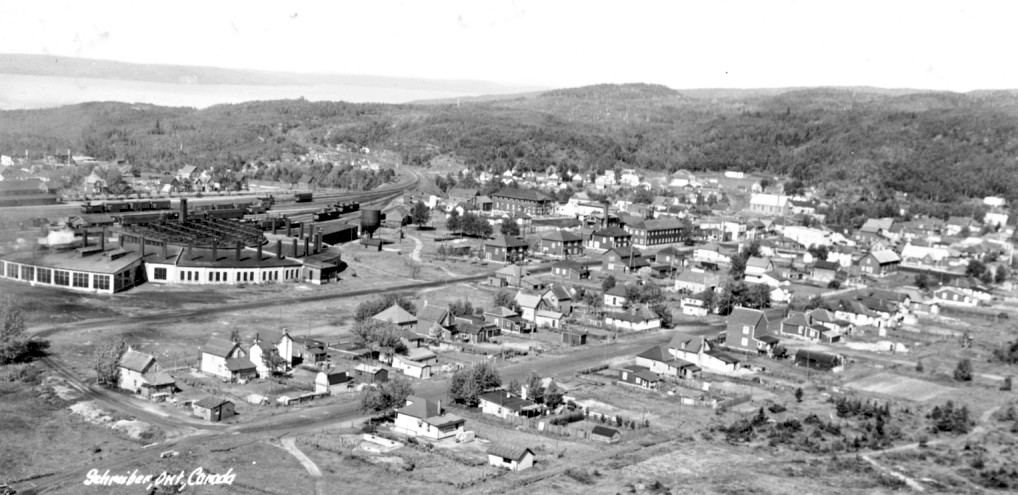

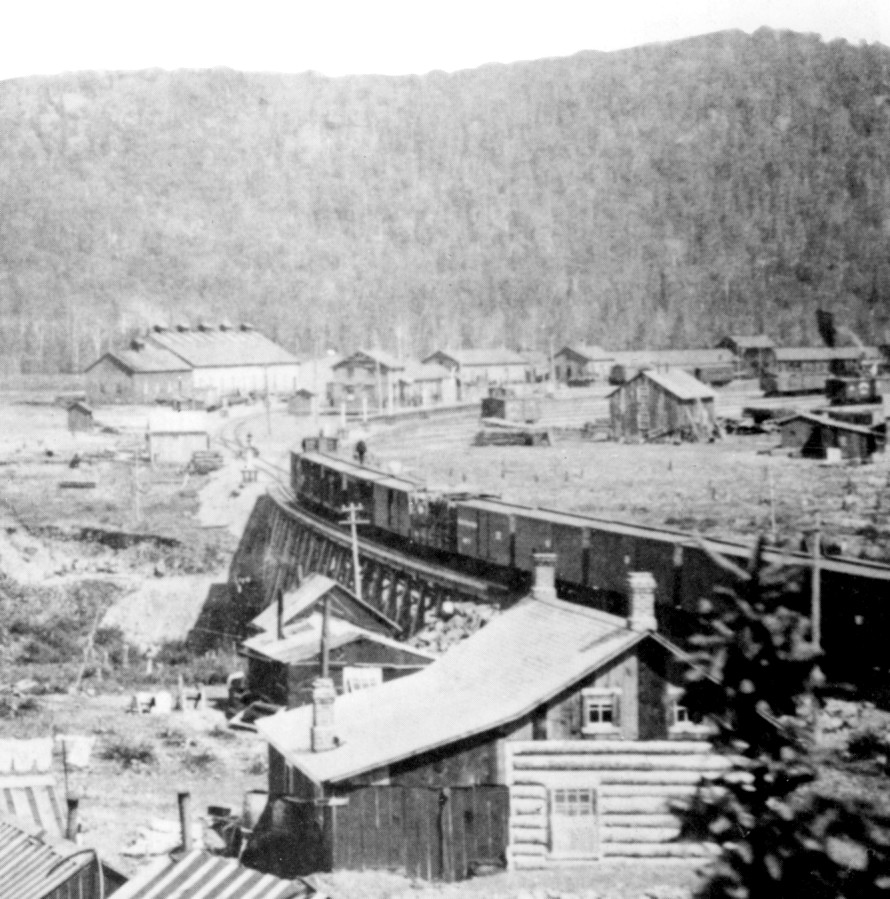

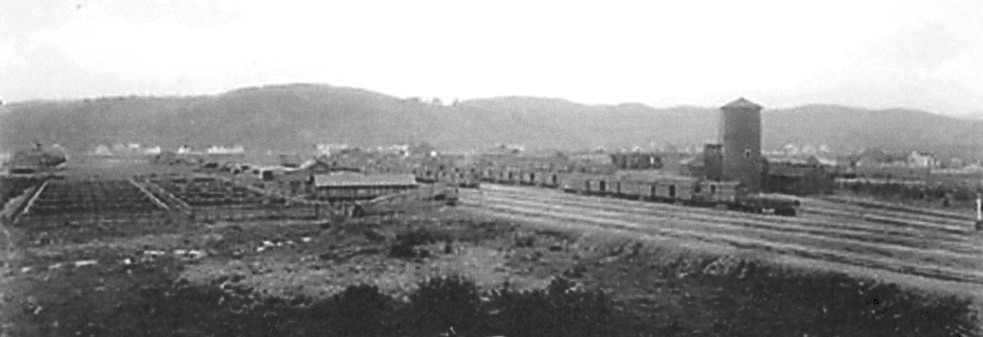

Schreiber before I went on brake.

Schreiber before I went on brake.

Where do we start with all the interesting details?

This is looking 'timetable east'

... so

going away along the track will take you to White River. The date is

probably 1890-1900. At this point the main railway buildings were north of the yard. It is possible, at this time, that

there were stockyards to the south of the yard near where the circa 1924 station

currently is.

There is a brakeman on the roofwalk at the three livestock cars just ahead of the conductor's van.

At the edge of civilization at the rear of the photo ... left

to right ... shop (?) ... passenger station and freight

shed ... food and boarding facilities (?) ... ice house (?).

Rough as it is, this photo seems to look timetable west. Stock pens are in use roughly where the 1924 station stands today.

The station and buildings in the 'trestle photo' above are probably beyond the water tower in this view.

During railway construction, nearby Rossport and Jackfish harbours

would have been more important than Schreiber for heavy supply. As you

can see from this map from the 1980s, Schreiber is isolated from Lake

Superior, except for the trail down to Schreiber Beach - i.e.

Isbester's Landing for supply boats during construction. The contour

lines show that the town and its facilities are ringed by high hills

and that the yard tracks had to be bent around these hills in order to

be located on relatively flat land. The blue squares are 1000 metres

across.

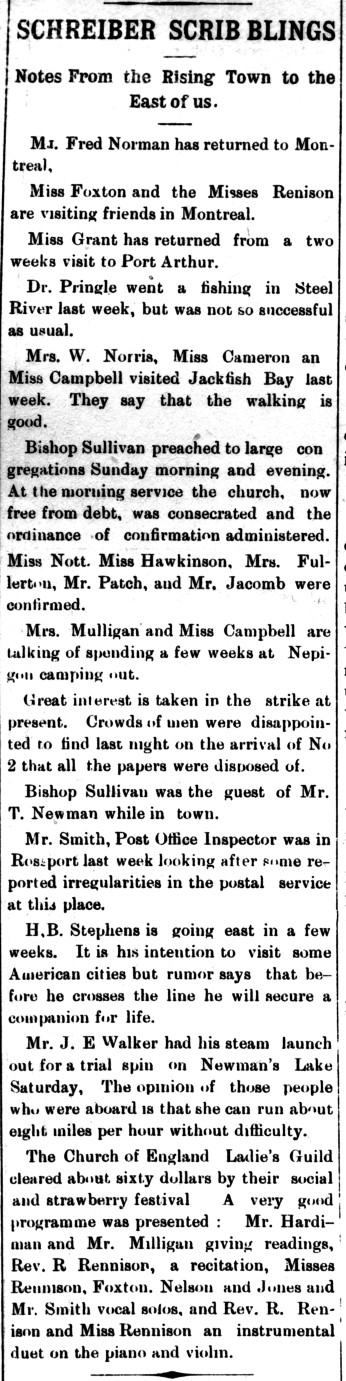

Schreiber existed for the railway, but gradually a more

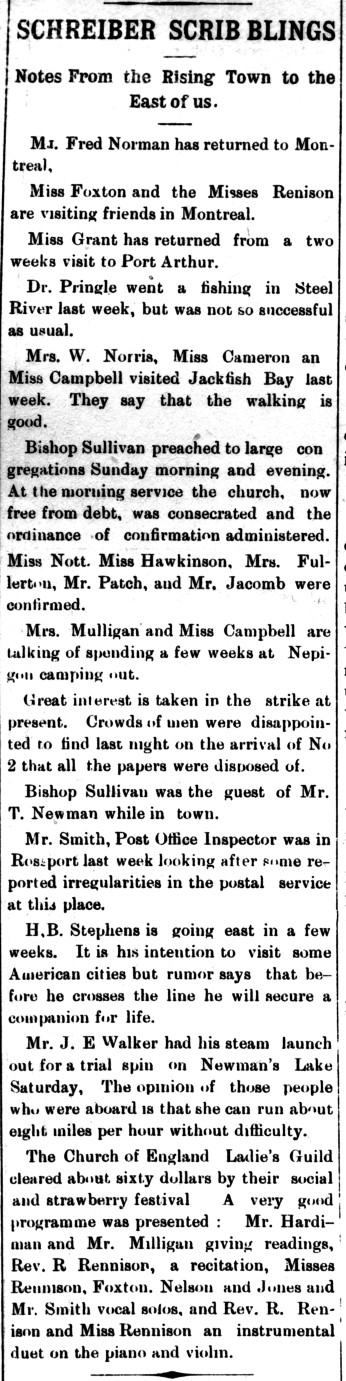

balanced community developed.

Here is a Schreiber news column from

the Fort William Journal of July 18, 1894 - nine years after the line

was completed.

"

The Strike" referred to above was the 50,000

worker Pullman Strike in Chicago which had been called by Eugene

V. Debs and the American Railway Union because sleeping car workers'

wages had been cut 25% and their union representatives fired. An injunction

was obtained by the U.S. attorney general (who also happened to be

a director on two railroad boards), and U.S. President Cleveland sent

in troops to enforce the injunction (34 strikers dead, hundreds of railway

cars burned by strikers) on July 4, 1894.

This violence occurred a week or so before

the newspapers would have reached Schreiber if they had not all 'been

disposed of' from CPR train Number 2 as recorded above. The railways were

BIG business and you didn't fool around with them. CPR officials had no

interest in keeping local workers in a company town up to date on strikes on other railways.

Speaking of officials ... from the same edition :

Schreiber's Italian Community

Immigrants from many countries and many other parts of

Canada have come to call Schreiber home over the years. The most noted

group all had an interesting common background.

Around 1905, Cosimo Figliomeni arrived in Schreiber from

Siderno, Italy, beginning a sequence of 'chain' migration of families

from Siderno to Schreiber. Put simply, 'chain migration' is knowing

someone who can help you find a place to live and help you get a job

- then you help someone you know, etc.

Back then, the railway was a very labour intensive business.

It is hard to imagine how it could have functioned without the contribution

of newcomers to Canada who often took on unpleasant, dangerous, lonely

and demanding jobs to become established in this sometimes harsh and

challenging country.

All year, the track would need to be patrolled and maintained

with heavy repairs being performed during the summer. This would employ

hundreds of workers on the Division.

In winter, with the roadbed frozen, shimming would be performed

to correct minor track defects. Cold and brittle rails breaking under

the pounding of trains would need to be replaced. Snowstorms would bring

a great demand for switch cleaning to keep the yards and sidings functioning.

Slides of rock, snow, and ice would need to be cleared. Inevitably, trains

suddenly coming into contact with winter track defects would require labour

to clear derailments and rebuild the track.

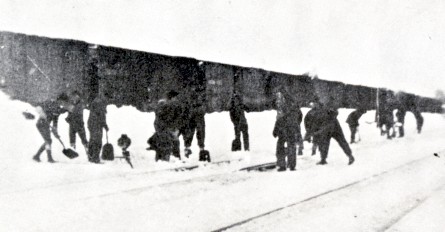

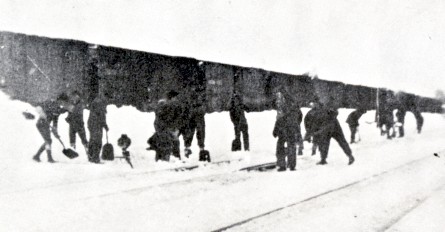

White River yard switch cleaning in the 1930s - from 'Pictorial History'

White River yard switch cleaning in the 1930s - from 'Pictorial History'

To maintain safety, trackwalkers were used in a number of lonely

areas on the line which were likely to be struck by rock and snow slides.

The waves and ice of Lake Superior storms could also attack the right

of way. These workers would be out in all hours, and in all weather,

to inspect the track and signal trains that it was safe to proceed if

all was well. This was particularly important before the passage of a passenger

train.

Another lonely job would be to maintain the water tanks used

to refill steam locomotive tenders. All year, the water pumps to fill

the tanks would need to be operated. During the winter, the fires in

heaters at the base of the tanks would also need to be maintained to keep

the tanks from freezing.

Spring thaw, heavy rain and beaver dam flooding repairs; ditch

and culvert maintenance; brush clearing; bridge and building maintenance;

locomotive servicing and car repairs; inspecting journals and topping

them up with oil; hauling blocks of cooling ice; maintaining kerosene markers

and switchlamps ... there seems to be no end to the list of jobs the railway

needed done.

Today, descendants of the immigrants from Siderno are said

to make up half of the population of Schreiber.

To understand the history of Schreiber is to understand the

contribution of those who worked under the most difficult and dangerous

conditions to keep the trains rolling.

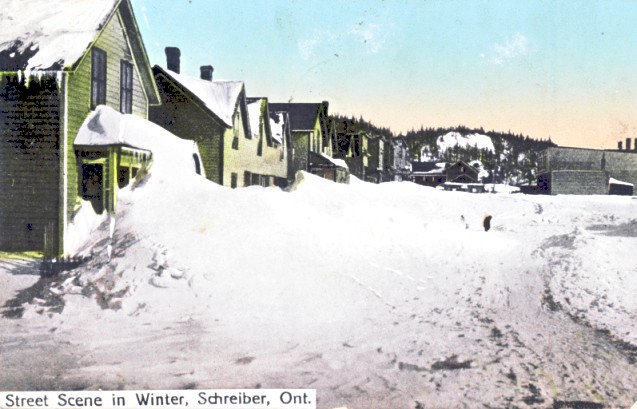

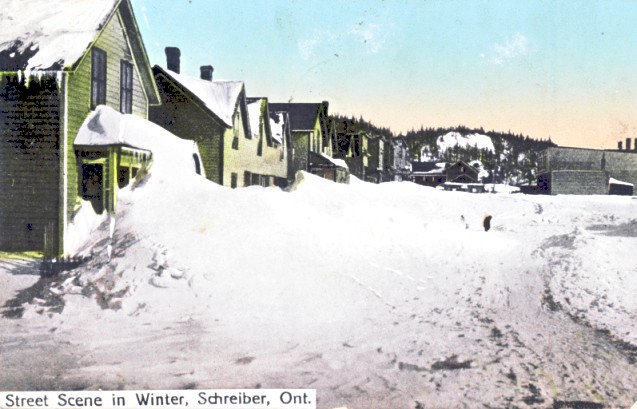

The message mailed to Red Deer Alberta reads:

The message mailed to Red Deer Alberta reads:

"This is pretty true to life.

Gee I think all the snow in the world is here,

and more to come and it's cold."

Schreiber Grows and Changes

Begun in the 1930s, the Trans-Canada Highway was not

completed in the region as a through road until 1960. So the

early development of both Schreiber and White River was centred around

the railway station and yards, beginning with the CPR's completion in

1885.

- Water transportation was minimal because neither had good harbours

on Lake Superior.

- There were few roads and no through roads in the early years.

- There were few motor vehicles then.

- The towns existed only for the railway as single industry towns.

The railway provided Schreiber with:

- Some company housing, particularly worker dormitories and houses

for officials who were transferred to Schreiber.

- Waterworks.

- Coal oil street lighting and eventually a diesel motor generated

electrical system in 1936.

- Telegraph service with the outside world with some telephones

in the late 1930s.

Social services were provided mainly by the churches. The

YMCA was one place where some community events were held and it was

the place where travellers and transferred or "bumped" railway workers

could get a room. Retail stores, their goods transported in by the railway,

also became established.

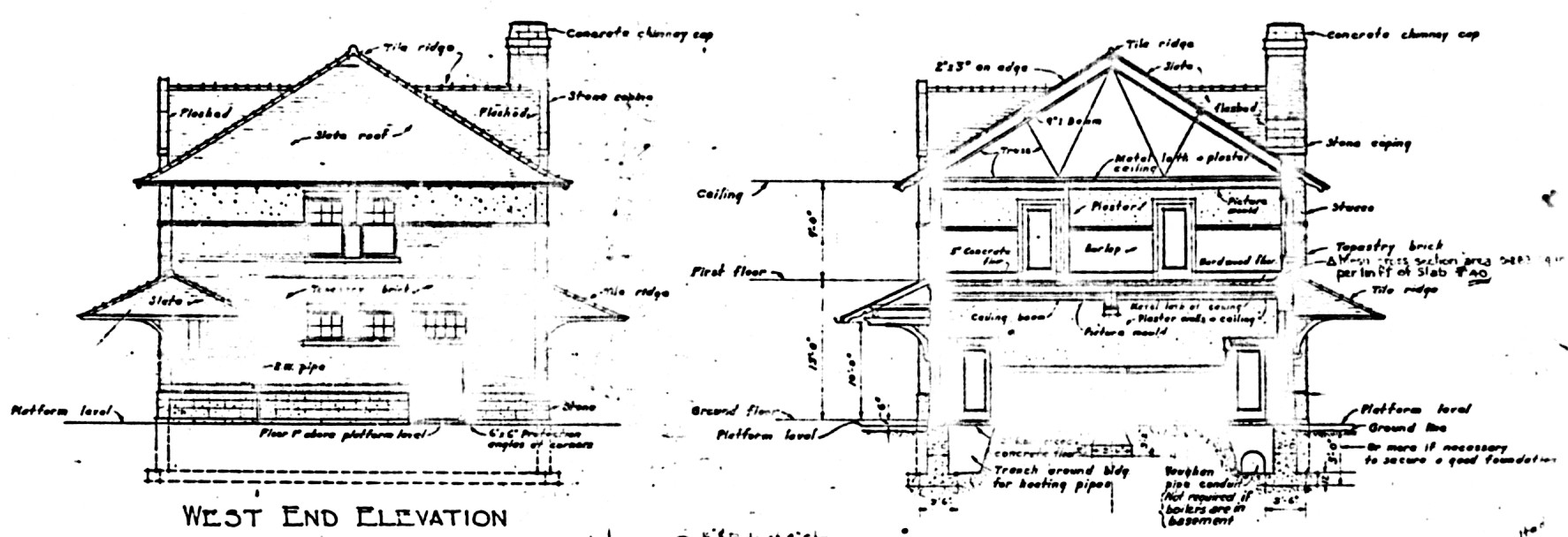

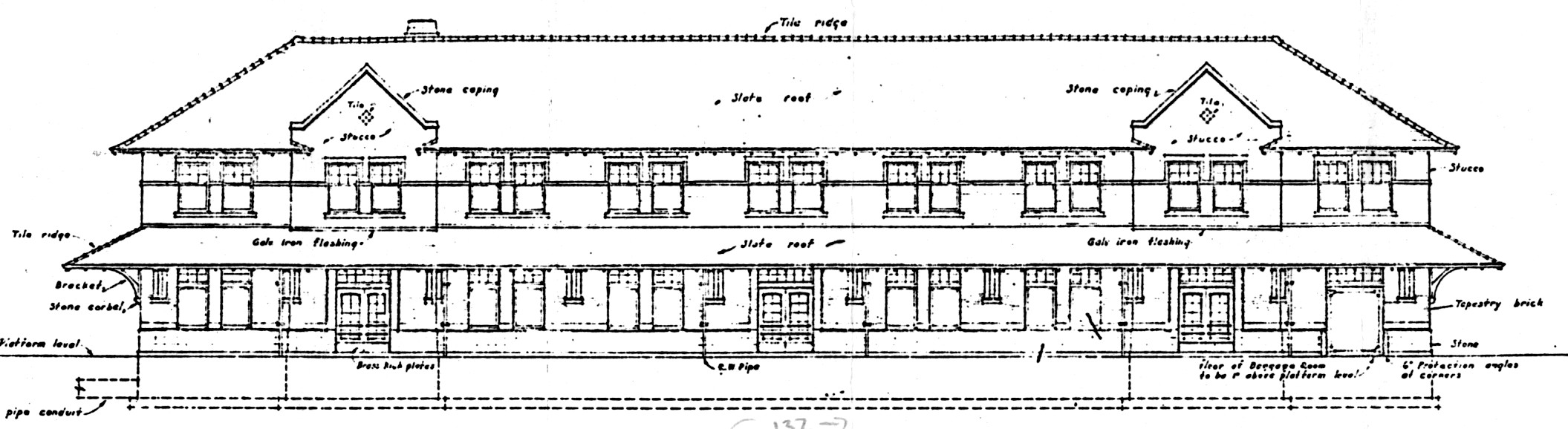

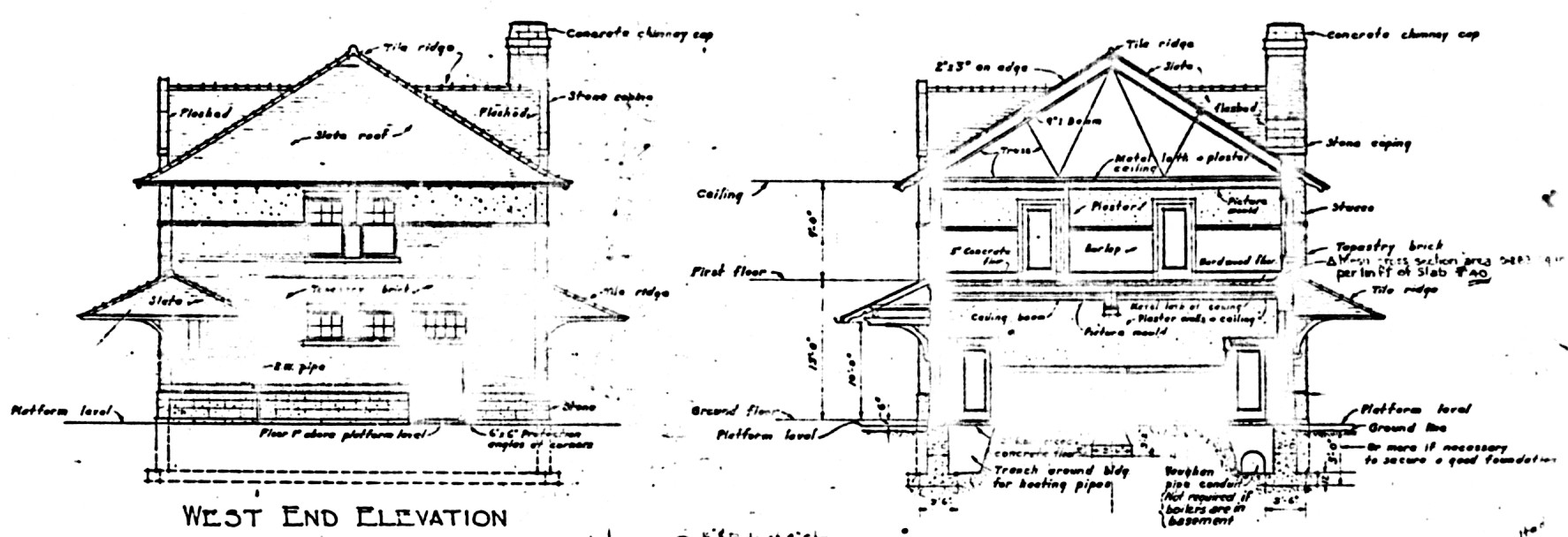

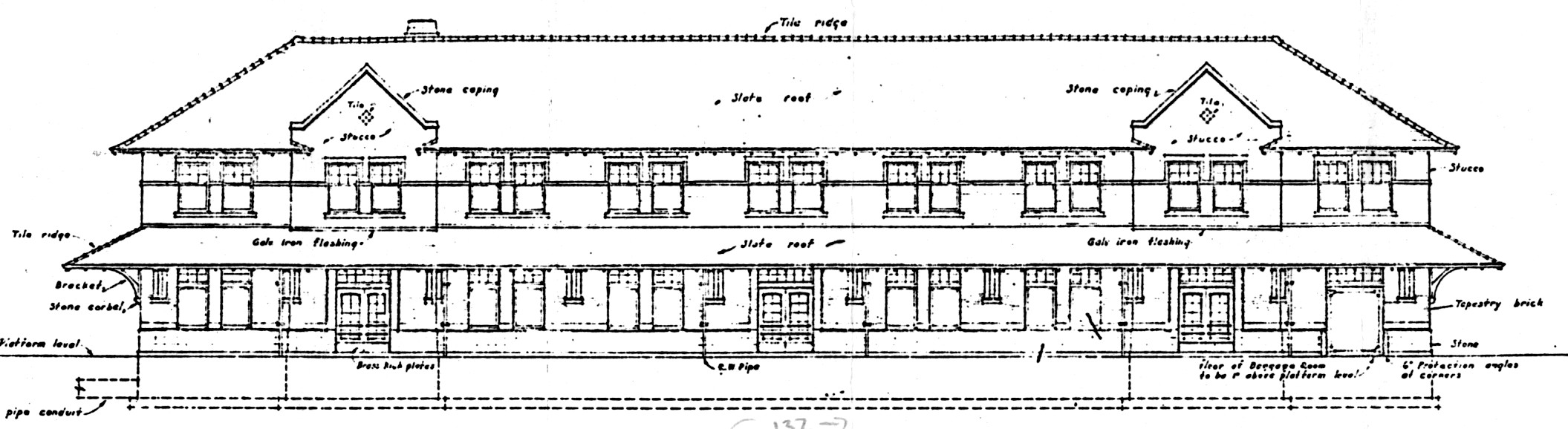

My brother obtained the following photocopies of diagrams for me years

ago. They show the plans for the proposed station at Schreiber, dated

1924. They're not presented because they are beautiful ... but because I

think others should have and preserve the history of the CPR line north

of Superior. It was this building which made Schreiber the headquarters

for the division. With this came the salaried positions which - I was

told in 1977 - made Schreiber 'the town with the highest per capita

income in Ontario'.

With the completion and opening of the Trans-Canada Highway from

Sault Ste Marie to the lakehead in September 1960, the Schreiber I knew

evolved.

To me, the most memorable features

of Schreiber were:

- The friendliness of the people - everyone was very helpful to

a teenager arriving in town to 'go on brake'.

- The importance of the railway to Schreiber and vice versa (i.e.

the division offices and the shops to repair rolling stock).

- The silence of the town and the height of the snowbanks - as

I walked to work in the middle of the night in a snowstorm.

With the opening of the Trans-Canada, 'getting over the road' took on a new meaning.

Back in these days professional salaries were probably around $1000 per year.

Old cars are always interesting, but also take note of the local telephone exchange in this 1965 flyer.

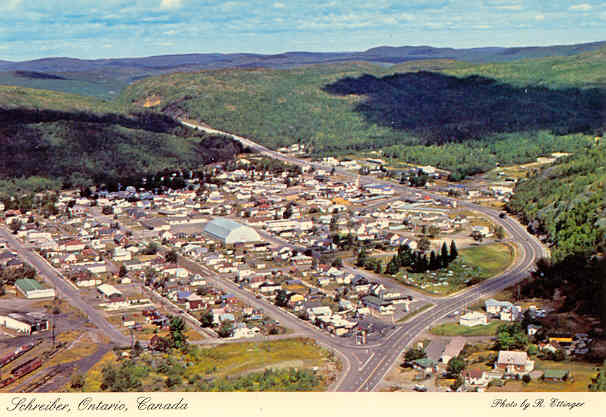

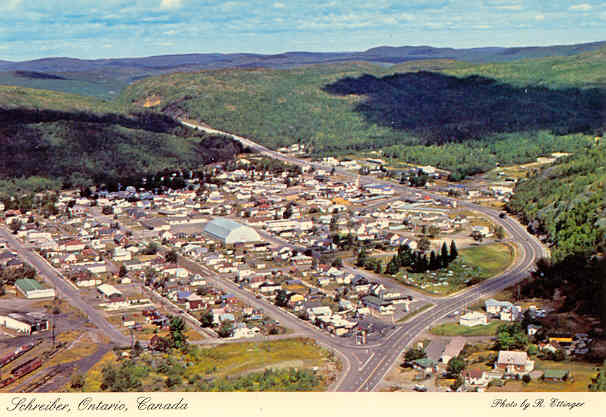

This is the part of Schreiber which is north of the railway

tracks. You can see the gently rolling sea of forested granite sliced

by the Trans-Canada. In the late 1970s and the 1980s, perhaps more

emphasis was put on the Trans-Canada for Schreiber's future. This postcard

from that time only shows a few stub tracks and a couple of white roundhouse

stalls as evidence of the town's heritage.

About 500 people were employed by CP Rail when I worked there

in the late 1970s. About 120 more were employed by the expanding Kimberly-Clark

mill in nearby Terrace Bay and there was a housing crunch in Schreiber

as construction workers crowded in to every available lodging.

Schreiber - a final trip back through time

The dispatchers, locomotive and car shops, division

offices, and half of the running trades employees (the trainmen)

are no longer to be found in Schreiber. Today, the Schreiber station

stands as a reminder of the thousands of railroaders who called Schreiber

home over the years.

Schreiber station in the 1980s.

Travelling back, here is a postcard from sometime in

the mid-1960s. The railway is prominent in the postcard photo by Harry

R. Oakman of Peterborough. A long summertime Train Number 1 with three

locomotives is changing crews at Schreiber station. The roundhouse is

gone, but the yard is full of paper cars and the car shop is in business.

1960s

Let's go back to the late 1930s. There is

no Trans-Canada. There is no through road featured

in the next postcard.

The town is centred around the railway facilities and buildings.

We see the roundhouse with its covered turntable (no shovelling snow

out of the pit) and the left edge of the postcard is smudged with coal

smoke. Company-built buildings stand out.

The westbound mainline - the sole reliable link

between eastern and western Canada for the first 30 years of the CPR

- quickly disappears among the forested granite hills.

1930s

Schreiber today is a thoroughly modern town.

But in this photo you can catch a glimpse of its origin.

In the year 2010, it will be 125 years

since the first of thousands of Schreiber running trades employees

started

pulling themselves up into the cabs of waiting CPR locomotives,

and swinging themselves up onto the steps of passing CPR vans.

Today, they continue to provide a link to Schreiber's beginnings.