JHE Secretan, Canadian Railway Surveying

Railway line location inthe good old days.

This section features a chapter of a book written by a civil engineer

who was involved at key points during Canada's railway building boom.

He gets a speaking part in Pierre Berton's film, The National Dream

, but is not listed as a historical figure in most Canadian reference

books.

His "fame" results from his ability to tell a good story and,

unlike most of the civil engineers of the day, his ability to put his

story in writing as entertainment. Perhaps this is why he fit so well

into Berton's efforts to popularize Canadian history and give us our own

historical "heroes".

Maybe this is why his version of some key events is now seamlessly

sewn into The National Dream.

In London, England in 1924, his adventures relating to the CPR

were published under the title Canada's Great Highway and the University

of Alberta has scanned the book, so you can read the whole thing on-line

if you want. I have just reproduced his earliest work on the CPR as a

representation of the conditions faced by civil engineers working to locate

Canada's wilderness railways through the Canadian Shield.

James Henry Edward Secretan 1852-1926

Secretan's account comes from the "Old CPR" - the CPR when it

was a government public work. A miniature version of the current British

Columbia had joined Canadian Confederation in 1871 on the condition that

a railway would be built to connect it to eastern Canada within 2 years,

and that the railway would be completed in 10 years ... so 1881, eh?

Then there was the Pacific Scandal, Macdonald's Tory government

was dumped, and the Canadian Pacific Railway idea was mothballed.

With Sir John A. Macdonald back in power in 1878, the government

dropped the "CPR as a public work " idea and connected with "The CPR

Syndicate" which included Canadian J.J. Hill, and Scottish

cousins George Stephen and Donald Smith - thus forming a trendy public-private

partnership. Hill hired American W.C. Van Horne as General Manager

during construction to finally bang the whole thing together - 1881 to

1885. And everyone lived happily ever after.

Thanks, but not so fast, Pierre.

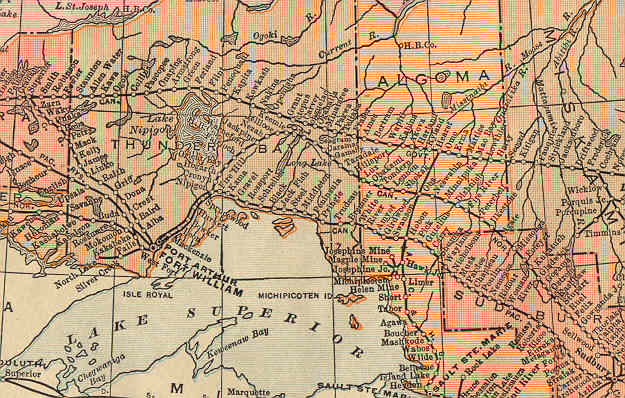

Here is a partial image of "Canada's Railway

Problem " as it appeared in a 1915 school atlas

... in a child's atlas, Mandrake.

Did we we really need THREE railway lines north

of Superior in 1915?

Ask the government - it built the top one and did

plenty to encourage the building of virtually everything you see.

- The bottom line along Lake Superior, the CPR, (built 1871-

... zzzz .... 1881-1885!! ) was conditional to unite BC with eastern Canada.

- Just above it, the Canadian Northern Railway (built 1899-1915)

was created to connect a healthy system of prairie branchlines with eastern

ports while avoiding giving the CPR the easy money for just transporting

CNoR boxcars full of grain.

- The most northerly line, the National Transcontinental Railway

(built 1905-1913), was created by the government between Moncton

and Winnipeg to give western farmers a way to bypass the "evil eastern

grain interests" by running directly to Quebec City. They also had high

hopes that this line would really open up northern Ontario and Quebec.

Secretan was working in this area - north-east of Lake Nipigon in

1871 for the "Old CPR" when he wrote the account reproduced below.

- We won't even get into the Grand Trunk Pacific's "me too" effort

between Winnipeg and Prince Rupert with virtually no prairie branchlines

to support it. It was to assume operation of the government

constructed NTR but couldn't hack it financially. Its parent, the Grand

Trunk, already ran between Sarnia, Toronto, Montreal and Portland, Maine

(seaport).

World War I cut off immigration and western growth for a while.

It killed the British mania for investing in Canadian railways because

capital and people were sucked into the war effort. The Great War killed

both the Canadian Northern Railway and the Grand Trunk/Grand Trunk Pacific

as independent financial entities.

By 1923, the two most northerly lines were absolutely and officially

part of Canadian National Railways - the overbuilt, federally owned

and supported network. The CNR competed with the CPR - a corporation

whose shares were traded on stock exchanges here and in London. However

no proud bastion of private enterprise, Berton's National Dream included,

can ever turn down government subsidies linked to politically popular consequences

- such as reducing freight rates for grain producers.

Were they all nuts?

Consider what railways offered:

- Created a non-American union of colonies, proudly under the Union

Flag of Britain, A Mari usque ad Mare, that's "Steel

of Empire " mister! (I'm just giving you the historical

Victorian-Canadian perspective.)

- Provided all-weather, uniform, "civilized" transportation which

could quickly haul heavy loads and people across the Canadian wilderness

- without getting the passengers all dirty and/or all wet in the process

- Provided all-Canadian communications systems (e.g. the telegraph

networks)

- Extended development into fertile, resource-rich new territories!

(shhh! - don't tell the First Nations folks - also

known as "Indians" outside of Canada)

- Increased business activity and employment, spelled GDP!

- Increased urban development ... factories to make everything from

steel bridges, rail, and locomotives ... to tickets, timetables, and dining

car doilies

"Surely, we in Government cannot go wrong by supporting all this good

stuff with":

- Cash grants

- Guaranteeing interest payments from railway bonds issued to banks

and other investors

- Free land! (I already told you

once not to tell the First Nations people!)

- Rebates for construction expenses

- Free rights of way (did you think railways actually bought

an "8 foot by 3000 mile" strip for their roadbeds?)

- Free surveying of townsites and farm lands on the railways' land

grants by guys like Secretan

... hmm, maybe too generous, but ...

Would Canadian history have come out the same if we had settled the

west via northern Ontario dirt trails connecting lake steamboat routes

... as the Grits wanted in the mid-1870s?

It would have been much easier for prospective settlers/squatters from

anywhere to travel via existing U.S. railroads

to the world's longest undefended,

unmarked, non-border, border ... and just walk across.

Would the map of Canada be different today if the governments hadn't

gone a little nuts (well ... OK ... a lot nuts)

supporting the railways

between 1890 and 1914?

Now think back ... think way, way back to 1871.

There are NO railways north of Lake Superior. Four-year-old

Canada-in-diapers doesn't have enough of anything for its coming

railway boom - well, maybe enough trees for railway ties, but that's it.

The American and British railway building booms have already produced

hundreds of engineers skilled in railway location. This works out perfectly

for Canada, because our transcontinental and western branchline railway

building booms are just getting started. American, Scottish and English

civil engineers will be in great demand. Freshly trained Secretan begins

work for the CPR at age 19.

Briefly - if such a thing is possible on this

website - how do you locate a railway line in northern Ontario?

Step 1 - Where do we want to go?

Whoever is paying the shot has a general idea of where the railway

should go. Hudson's Bay Company water-based trade routes are well-established

so there is a good body of knowledge about "the country". For example,

Secretan's 1871 group is told to head east from north of the top of Lake

Nipigon. It is possible that the area had already been scouted by a "Locating

Engineer".

Step 2 - OK, we're starting ... um ... exactly where are we?

If you can link to a documented "benchmark" just work from there.

Or... using a precision timepiece ... you have brought the exact time

with you from the Dominion Observatory in Ottawa. Like a gallant sea captain

on the faceless ocean, you can use an instrument to "shoot" the sun or

the stars because their movements are predictable. Their "angles" relative

to you at a given time, plus a few calculations, tell you where you are

- longitude and latitude down to a high degree of precision. Stake zero

is at ...

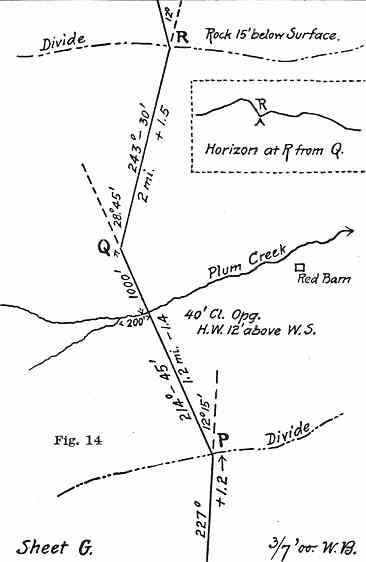

Step 3 - The Chief of the Survey Party does some reconnaissance

, on horseback if possible, and produces a sketch of a possible route

ahead which he gives to The Assistant (...Chief Engineer).

In the sketch, the Chief is laying out some tangents (straight

parts). The question is: is his "highly experienced eye" right? Has he

found a path through the Canadian Shield trees, hills, rivers, rocks and

swamps which can easily be transformed into a railway? Using instruments

to check his eye, are the grades and curves acceptable?

So the Assistant sees the Chief's "vision", the Chief has used

hand-held instruments to provide rough compass headings and distances

and has clearly marked where the tangents meet geographical landmarks.

The Assistant is in charge of the tripod-mounted instruments and the staff

which follow to do the accurate measuring work.

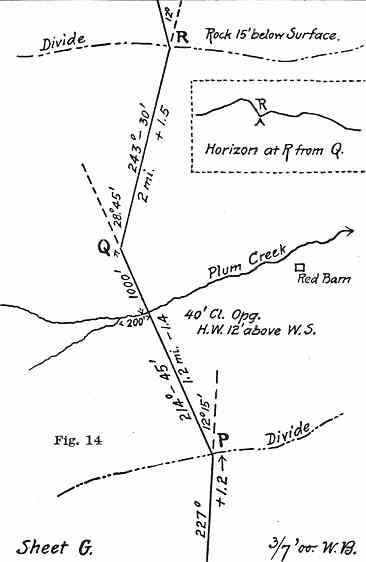

On the diagram:

Above the tangents are compass headings in degrees and minutes

(minute = 1/60 of a degree).

Below the tangents are their lengths and + or - slope

in per cent (2 units vertical over 100 units horizontal = 2.00%).

At each change in direction (P, Q, R) the relative

change in heading is also shown in degrees and minutes.

In this textbook example, with a sketch the Chief shows

visually where the Q-R segment should cut a ridge to help

the Assistant see exactly what the Chief is thinking.

Step 4 - As he works, the Assistant (with the Chief) gets a "feel"

for the extent of construction work do be done: grading, timber clearing,

cuts and rock removal, building embankments across muskeg, bridges, tunnels.

This is all recorded in notes.

Step 5 - Relative to the starting point - the first stake of your

"trial line" - each day's work is recorded on paper at night. Key points

on the map match stakes and other numbered markers which were placed as

the party proceeded.

In the end you have:

- A map of the local area around the potential railway route.

On the map is ...

- A plan for the line with all sorts of little math details

on angles, gradient, and of course ... distance. Key aspects of the plan

are linked to key physical features - sometimes in great detail.

- Semi-permanent land markers so anyone can match your paper

map and plan to the actual countryside.

- An idea of what construction must be done to build this potential

railway over this land - if there are no surprises.

Ultimately, some big wheel in an office in Ottawa and/or Montreal looks

at all this and determines if building your particular line is worth the estimated

cost to build and operate it. Caution: sharp curves and steep grades will

cost you money forever.

Members of a railway location survey party circa 1900 - listed

by "importance"

Chief of Party

Perform reconnaissance for the survey party and "be in charge"

Topographer, "The Assistant"

Supervise the party's work during the day as he interprets it through

the Chief's diagram. Should be experienced in construction and on all

the instruments. Makes notes on key features of the proposed line.

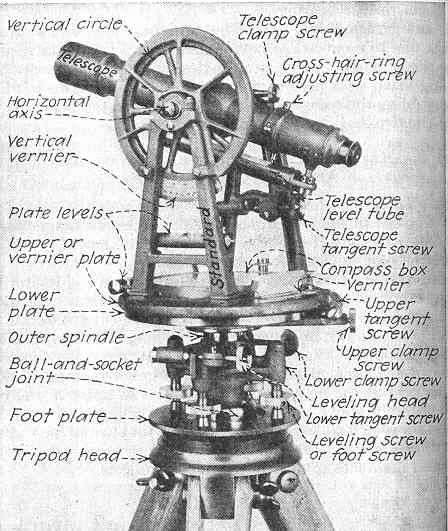

Transitman

Maintain and operate the transit (the heaviest instrument, the

"universal" surveying instrument - which can measure both horizontal and

vertical angles and "prolong straight lines"). The transitman also

keeps alignment notes and assists in platting (an old term for plotting

or mapping) the line at night. The "flag" (range pole) held by the rear

flagman enables the transitman to "backsight" - lining up his next

sighting point with his previous sighting point as he stands smack dab between

them. The transitman uses all sorts of elaborate processes and mathematical

calculations to nail down precisely where each important feature is.

Here is a transit from the pre-1940 era:

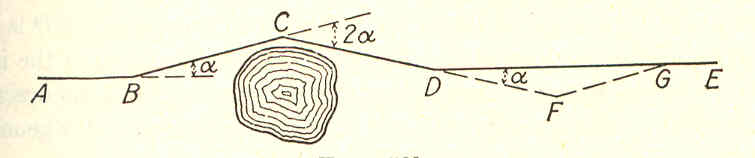

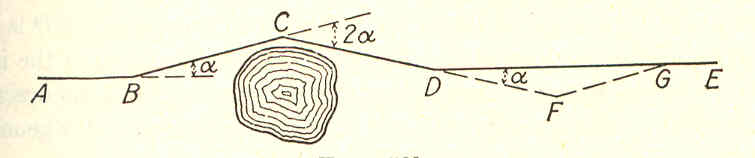

Here is an example of a party trick you can perform with

a transit - surveying a straight line in spite of an obstacle like a lake.

But I bet you have to know yucky math.

Draftsman

Create the "map" and "plan" of the potential railway line - as

it evolves, with data from the others

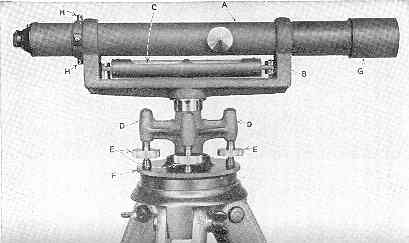

Levelman (our man, Secretan)

Maintain and operate the level - which is used to survey the gradient

of the line. Take notes to supplement the Assistant's on local physical

features. Assist in platting at night. Operating a level "demands less

professional experience than the transit ... may be filled by some young

graduate engineer ". Secretan's "dumpy level" (the original

design was short and stout in appearance - dumpy) was the most common type

used. On a dumpy level, the telescope is permanently connected to its supports.

The level is set up to always sight parallel to level ground, aiming at a

calibrated rod held by the Rodman. So you read the height difference

on the rod through the telescope, you chain (measure) the distance to the

rod at ground level, and you can then calculate the gradient.

Here is a dumpy level. A is the telescope

and C is a spirit level so you can ... level the level!

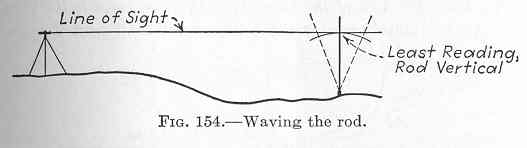

Here is the type of fun the Levelman and Rodman would

have together.

Waving the rod: as seen through the telescope - the lowest value is the

correct value.

Head Chainman

Measure distance with a 100 foot chain (later steel measuring tapes)

and set the pace for the party - considering the relative speeds of the

axmen, transitman, levelman, and other party members. He is the foreman

of clearing, chaining and staking the line. The Rear Chainman brings

up the rear of the chain and assists in counting off each 100 foot segment

- and fractions of 100 when necessary. Starting at zero, the Stakeman

is responsible for semi-permanently marking the spots used by the transitman

and levelman for their measurements, and any other special landmarks.

Other members - by "importance" - Cook, Boss Teamster, Front Axman

(in charge of the party clearing the line ahead for the tripod instruments

and chain), Axmen, Teamsters.

As you will read, it sounds as if there were no horses in Secretan's

group and that the duties of Topographer and Transitman were assigned

to the Assistant. A textbook suggests it is better to have the Assistant's

head up, concentrating on the Chief's diagram, the land, and the whole

group ... with the Transitman able to concentrate solely on the

transit, making measurements and notes, and performing calculations.

You can bet on there being a high proportion of axmen and porters

in Secretan's horseless party as they crashed, hacked and waded their way

through the northern Ontario forest.

Secretan's account

- Secretan has a "typical Victorian view" of First Nations

people.

- However, whenever the party runs into trouble, notice

whose technology, knowledge, and skills they call on.

- Here is Secretan's north and east from Lake Nipigon account.

- Two illustrations come from a 1924 travel book on Lake

Superior written by T. Morris Longstreth.

First Surveys 1871

I was appointed by my old friend, The Hon. John Henry Pope,

who somehow had taken a sort of fancy to me, partly I believe because

I used to amuse him by making a fourth at euchre in his quarters at the

old Russell House Room No. 78. I can just remember the Hon. Peter Mitchell

often being one of the party and some others, mostly old enough to be

my grandfather.

I always looked upon "John Henry" with awe and admiration and

invariably considered him to be the Abe Lincoln of Canada, another of

my heroes whose life I had devoured with great gusto. [Abe and Mark Twain,

I still believe to be the greatest men America has produced. I hate

to offend Chauncey Depew, but he may never know it.]

The repellent rocky shore of Lake Superior was not considered

at first in the search for a practicable route for the great overland

highway, but a more northerly line was to be explored with lighter work

and easier gradients. Thus it was that I found myself, one bright Spring

day, en route from Collingwood to Red Rock, Nipigon Bay, on board one

of the old-time side-wheelers, armed with a brand new little English Dumpy

level on my shoulder, a full fledged Leveller of Division H under a nice

old gentleman named Johnson, with orders to run from some point about

twenty miles North of the North end of Lake Nipigon in an Easterly direction

to meet Division G, under an Engineer named Armstrong, running West, to

link up our line with his and return home unless otherwise ordered.

So far all was sunshine and happiness. My immediate senior

officer was a long lank Nova Scotian named Schurman, whose duty it

was to take charge of the crew, run the transit and make the observations

- subsequently I made a few myself.

I remember we had a splendid time at Red Rock on the Nipigon

River, about thirty odd miles from Lake Nipigon, with many heartbreaking

portages, some of them many miles in length. The Hudson's Bay Company

had a post at Red Rock in charge of Mr. Crawford, the Factor, and there

we were camped several days waiting for boats to arrive for what little

navigation there was on the Nipigon River. These came up in the shape

of Ottawa River Lumberman's Bateaux, and they were forty or fifty feet long

if I remember rightly, and I do remember that they were heavy

enough when we commenced to drag them over the numerous portages.

A sport fishing party on the Nipigon River circa 1920

A sport fishing party on the Nipigon River circa 1920

There was a certain amount of novelty about this trip and there

was, too, quite a lot of discomfort, but all's well that ends well,

and at last we reached our initial point. Here we blazed the first tree

that had ever been blazed in that locality and certainly planted one

of the first stakes ever planted marked zero, of that particular Division

for the future line of the great C.P.R.

The regular routine of a survey party would probably not interest

my readers, and it is enough to say that we turned out very early in

the grey morn, worked hard all day in all weathers, ate three times a

day regularly (on the principle of Josh Billings, who wrote to his wife,

"Enclose please find ten dollars, if you can!") and the slept the

tired and dreamless sleep of the weary. Every day was precisely the same,

and the routine was the same for months on end.

The country assigned to us was most uninteresting, consisting,

as it did, of a series of muskegs occasionally intersected by high

rocky ridges; the timber was small scrub spruce of a most funereal aspect

with long pendant weepers of black crepe - no birds, no beasts, no fish,

no life, no nothing! Millions of poisonous black flies by day and mosquitoes

at night. It seemed to me that a convention of all the flies in the world

was being held there.

We were no doubt the first human bipeds that had ever traversed

that God-forsaken country, - although perhaps we didn't fully realize

the honour and glory of all this at that time. Wading knee-deep through

muskegs all day and fighting mosquitoes all night, and living on salt

pork of the Crimean period and beans, with dried apples for dessert,

was our daily routine, until at last early morning frosts warned us that

October had arrived. We were nearly one hundred miles from our starting

point and supplies were almost exhausted. Our pack animals, mostly French

half-breeds, had returned from the base with the fatal announcement that

no fresh supplies had arrived. Well, here we were, thirty-eight men

and one dog, about two hundred miles from where we knew there was plenty,

"Flat Rock Portage," on the shores of Lake Nipigon.

So the nice old gentleman, previously mentioned, our Chieftain,

in the proverbial language of the prize ring, "threw up the sponge,"

dressed himself up in a long black coat, put on a black necktie, and

resigned himself to his horrible fate.

The Wolf at the Door

The elongated Schurman and I now had a committee meeting of two and

decided that something had to be done, and that quick action was absolutely

necessary. One of us should take the crew out over our line, now about

110 miles long and the other take his chance of meeting the party that

was supposed to be coming from the East, finding his way through the bush

on a compass bearing as well as he could.

We tossed up for it. I don't think there was much choice. Anyhow,

he won and decided to take an Indian boy and go East to try to find

Armstrong of Division G, while I was to take the men down over our line

in the hope of meeting relief or at least of finding it in the shape

of supplies at our initial point.

We shook hands and parted next morning, he with a compass and

a few pounds of split peas, and I with thirty-eight men and a dog,

about half a day's rations of flour but nothing else except the hope

that "springs eternal in the human heart." I cached everything that weighed

anything, and without tents, blankets or grub, we started our long tramp

back over the hated muskegs and rock ridges. It was getting cold at night

as we huddled round our fire, but during the bright frosty October days,

the sun shone on us and took the frost out of our clothes and put some

warmth into our hearts.

The only luck we had was finding any amount of the little buds

that grow on rose bushes, full of seeds, which washed down with plenty

of swamp water kept life in us and enabled us to do nearly thirty miles

a day between daylight and dark.

We Arrive at Ombobiqua River

About four days and nights after I parted with the lengthy Nova Scotian,

we arrived at last at our starting point and found - nothing !

There were a few foot-sore stragglers, whom I sent back for the

next day.

At noon a bunch of Cree Indians stole softly down the river

in their canoes and were much surprised to discover my ragged and hungry

mob of white men. We had money, but they did not seem to understand the

rate of exchange.

But they had white fish, and we had undershirts of a gorgeous

scarlet hue which appealed to their simple tastes just as the fish

appealed to ours, so exchanges were rapidly effected. After much haggling,

we also secured a few of their birch-bark canoes and proceeded down stream

to the head of the lake, where I pictured a magnificent depot of supplies

and in my mind's eye, goaded on by the promptings and suggestions of an

empty stomach, I saw vast hoards of succulent provisions, the much despised

iron-bound barrels of Crimean pork in the front row, flanked by barrels

of flour and other luxuries.

First Nations women building a birch bark canoe circa 1920

First Nations women building a birch bark canoe circa 1920

At this stage of my disappointment, I suggested to the aged

Chieftain before-mentioned that somebody had better try to reach the

known depot at Flat Rock, where stores must be found, and modestly volunteered

for the venture.

So I left that night in a fathom and a half bark canoe with

one half-breed boy in the bow. Nipigon Lake has a number of deep bays

many of them ten or fifteen miles across from point to point, impossible

for my little craft in rough weather. So wearily we tightened up our

dinner straps and paddled round these bays as far off the land as we

dare. After a couple of days and nights of this work, I remember, we

landed on a rocky shore and my "crew" proceeded to fell a tall, stately

dry ram pike to make a fire, as the nights were not too sultry.

With a crash about thirty feet of the stately old pine top came

down and went through the bottom of our last hope, the little canoe,

which had been hauled up on the flat rock. This looked like disaster,

if not death, but we had done so well and got so far without meeting the

grim Reaper face to face, so we simply looked at each other and then proceeded

to look for gum and birch-bark, also cedar for ribs. We found all these

necessary materials before daylight and began shipbuilding.

About noon, we sighted an ancient aborigine of the female sex,

who, after much waving of shirts as S.O.S. signals on our part, bashfully

came within hailing distance and informed us we were only six miles from

Flat Rock Portage!

Our troubles, at least for the present, were over.

It did not take long that morning to paddle our little patchwork

round to Flat Rock Portage, where we found a big camp or depot full

of supplies and my party, all now well fed and happy, they having been

rescued by the Commissariat boats busily transporting more barrels of

sugar to the head of the Lake.

I was joyously received, having been reported as missing

Next day our outfit moved down stream to Red Rock on Lake Superior

to await a home-going steamer.

But what about my friend Schurman? His experience was perhaps

worse than mine, although he chose what he considered the easiest way

out.

In a few days the old Cumberland hove in sight, bound

up to Port Arthur and then to Collingwood, and the first man to come

ashore was my long lean friend Schurman, looking leaner than ever. He

soon told me his adventures since we parted. As I said before, he left

me with one Indian boy, a bag of split peas and a pocket compass.

The first day he travelled through the bush in an Easterly direction,

hoping every hour to get some tidings of the on-coming party under Armstrong,

but without finding any sign of them. The second day he was rather exhausted

from lack of food, and as there was still no sign of a human being at

night, he began to fear he might be travelling either North or South

of, and parallel to, Armstrong's line. On the afternoon of the third

day he struck a big lake right across his course and then began to despair

and abandon all hope of ever being rescued.

In this cheerful frame of mind he was considering the desirability

of blowing his brains out when towards evening he saw a canoe containing

an ancient squaw who was out fishing. The Indian boy, nearly crazy with

fear at first and now delighted, soon attracted her attention, and before

dark the old squaw had taken them to Armstrong's camp on the Pic River

where, very weak and exhausted, they were nursed back to life and later

taken down to Lake Superior and so on to Red Rock, where we met. It appeared

that Armstrong had run out of supplies and was on his way to civilization,

having been unable to finish his line and join up with us.

Thus ended my first experience on a very small link of the great

chain stretching across the vast continent.

During that winter in Ottawa, I had the honour of shaking hands

with Sir Sandford Fleming, who kindly enquired whether I had not had

"a rather hard summer?" When I told him we were four days without being

troubled with food, he simply said, "And were there no squirrels

you could shoot?"

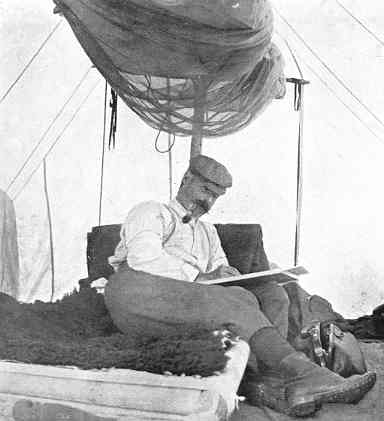

J.H.E. Secretan in his tent.

Notice the mosquito netting above and the buffalo hide for a blanket.

Back to sitemap