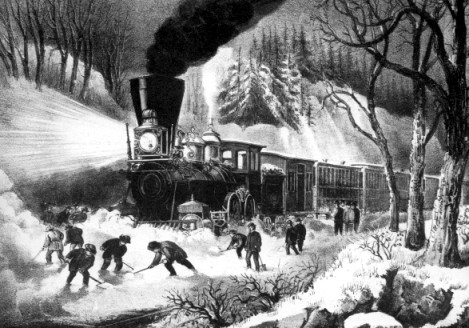

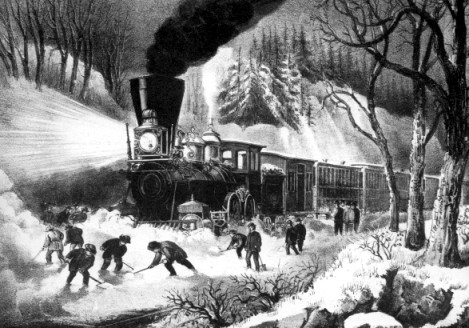

Here on the morphologically more accurate Currier and Ives Railroad, USA,

they apparently had miniature people to get out and shovel

when the large, mighty locomotive got stuck.

Early railways in Canada didn't

even attempt to operate in winter. Getting the light locomotives over

the rickety track was hard enough in good weather. Over time though,

the possibility of providing year-round service, thereby maintaining

railway earnings through the winter, led to the development of a

succession of technologies to remove snow from the right of way.

The track structure consisted of rails, untreated wooden ties, and an

earth roadbed ... the latter being peaked like a roof along the

centre of the track to shed water. As railways evolved, the

creosote-saturated ties were laid on/into a bed of crushed rock to

improve stability and drainage.

Water causes the track structure to deteriorate, resulting in

derailments. The best place for a railway would probably be in a desert

at constant room temperature.

In the real world, water eroded the earthen road bed. Where it

saturated the earth, it created soft spots where the rails would sag as

a train passed. It got into hard to reach places and expanded when it

froze loosening everything up. Water bad. Ice badder.

... by the way ... if a roadmaster ever sidles up to you and says

he has a riddle for you, the answer will be ... drainage ! drainage !

drainage !

So there were really two significant problems snowy winters created for North American railways :

- Early locomotives didn't have the power and/or adhesion

(grip on the rail) to push through large accumulations of snow over the

track.

- The

track structure and safe operations were affected by water, snow, and

ice ... going through thaw (infiltration) and freeze (expansion) cycles.

Early Snowplows

On our smug British North American railway, we have this famous illustration

"Triumph of the Snow-plough" circa 1860.

By the way, in my historical heart, I spell 'railway snowplough'

but people using search engines will use 'snowplow'.

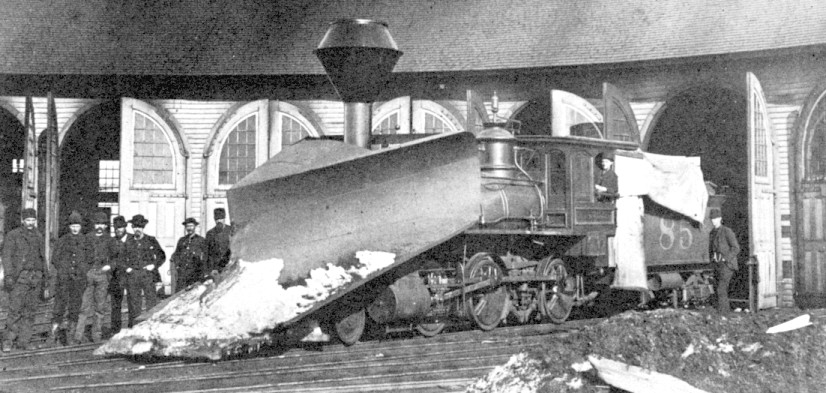

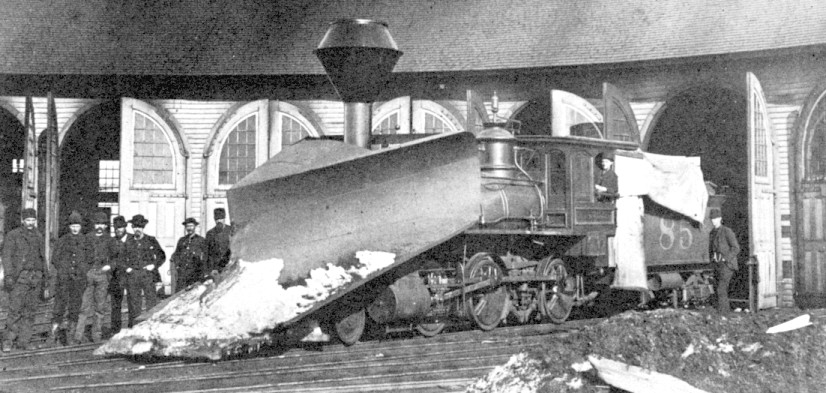

In this circa 1875 photograph on the Union Pacific, you can see an early deluxe snowplow.

For the season, it is mounted on a freight engine with six, smaller driving wheels ...

smaller wheels compared to the fast running 'high-drivered' Currier and Ives example above.

So this locomotive should have better adhesion and operate in a 'lower gear' against the snow load.

As the snow rises up the 'shovel nose' of the plow, it will push down on the front half of the locomotive,

making the drivers even less 'slippery'.

Notice the white 'winter curtains' over the open back end of the cab which also cover the fuel load in the tender.

At higher speeds, powdery snow will fly through the air making it impossible to see ahead.

Snow will blow and pack into every open spot ... that's why the curtains are necessary.

These curtains were no substitute for a properly enclosed cab ...

the fireman would bake ... then freeze ... as he walked between the firebox door and the fuel in the tender.

Also notice that no headlight is visible on the locomotive with the plow mounted.

Pilot Plows

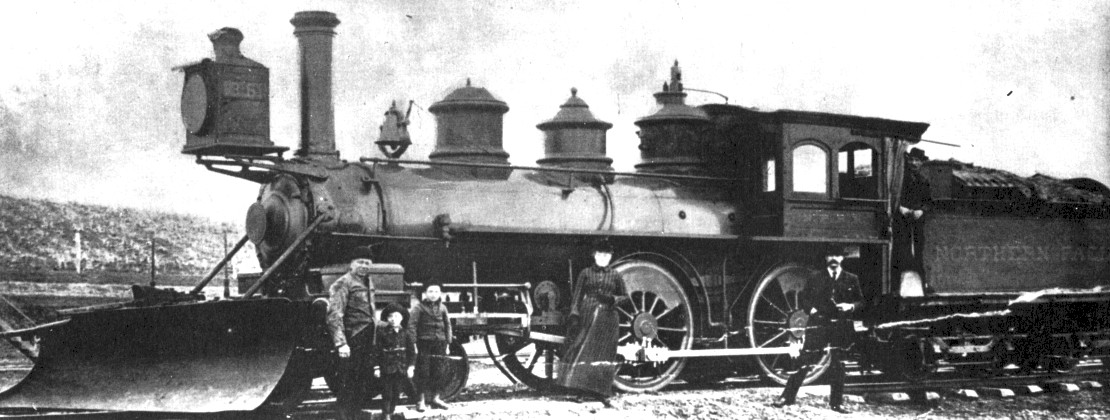

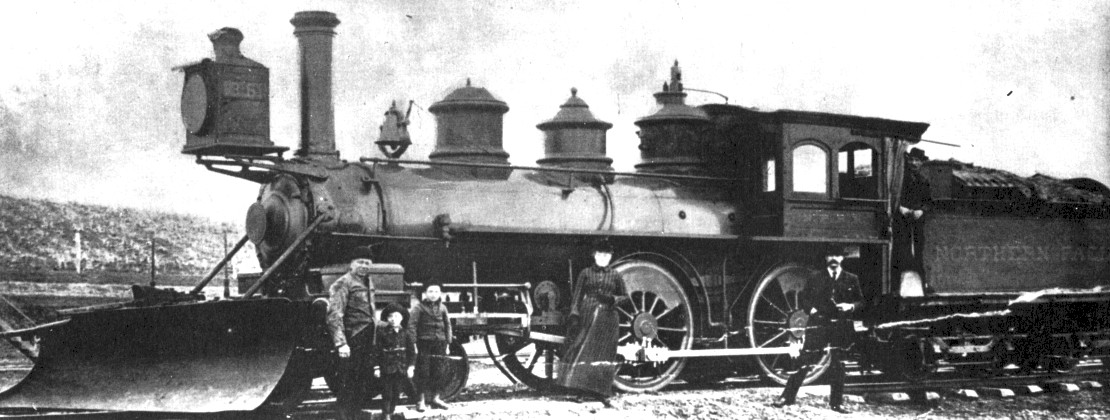

A few years later, a poor old photo of a poor old locomotive on a branch line.

Northern Pacific branchline clearing equipment in the state of Washington, 1891.

With a plow mounted on the engine's pilot (the cowcatcher area) there is probably a good match

between this locomotive's power/adhesion and the snow's resistance - if the snow doesn't get too deep.

If you had trains operating with regularity over a line during a snowfall ...

and each locomotive had a pilot plow ...

and the trains were operating sufficiently fast enough to 'throw' the snow back.

You might not need to run special plow trains to keep the line open.

Today, massive high-adhesion diesel locomotives with more subtle built-in pilot plows,

leading very heavy trains with unstoppable momentum,

take advantage of this principle to routinely keep most lines clear during winter.

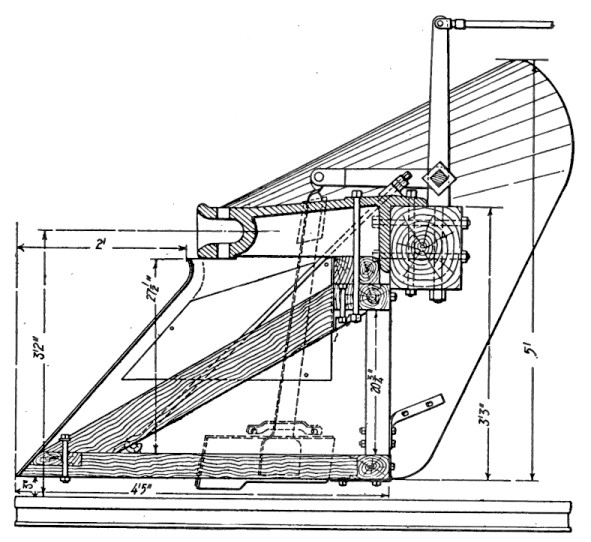

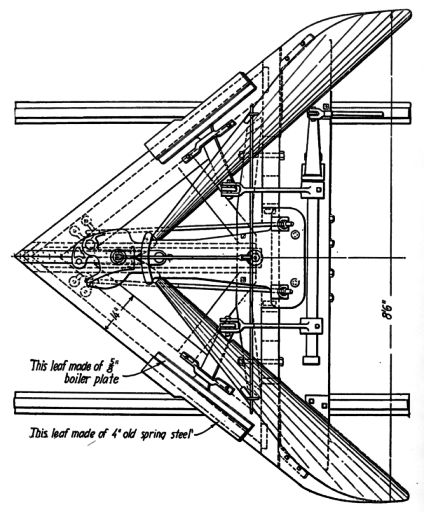

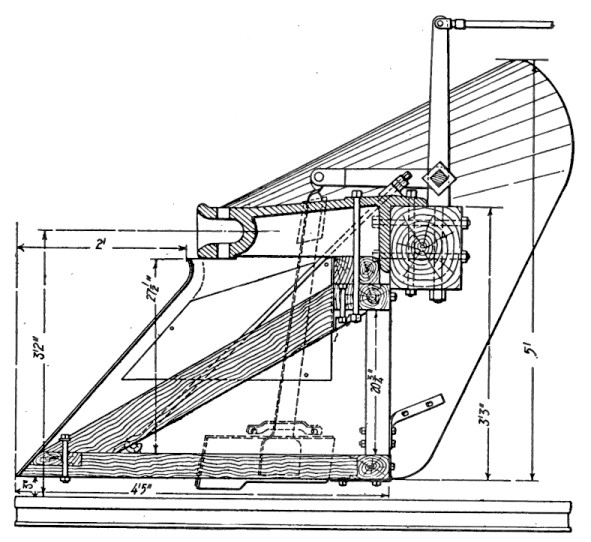

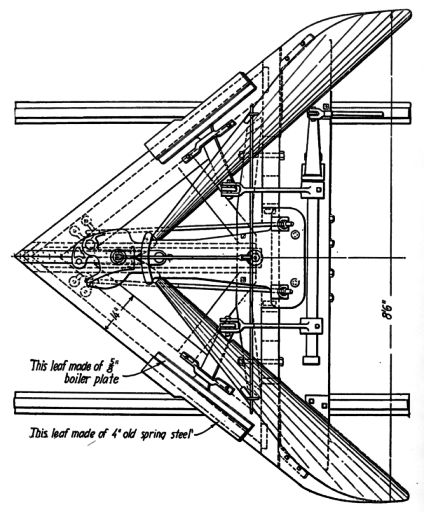

Here is an x-ray side view of a pilot plow.

Why not build your own as a weekend project !

Like those above, this plow is from the old 'link and pin' coupler era ...

where the smooth slope of the plow breaks, you could insert a coupling bar and drop a pin.

As our technology evolves, you may have noticed another refinement within this plow ...

Linkages zig-zag from the very top down to a white plate just above the track rail at the very bottom.

An operator in the locomotive cab (out of frame to the upper right) could push the linkage forward ...

this would force that bottom plate down below the level of the rail.

Consider that the flanges that keep railway wheels on the track are INSIDE the rail.

Consider also that railway track and ICE/SNOW/WATER don't mix.

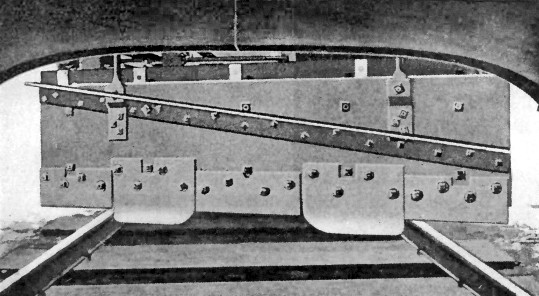

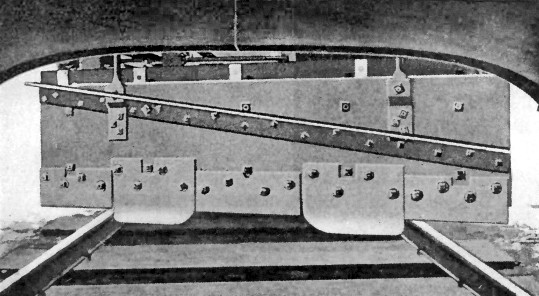

X-ray top view of a similar pilot plow.

If you can dig accumulated snow and ice out the space between the rails ...

particularly where the wheel flanges run ...

you'll have fewer derailments and a happier railway.

The 'FLANGER' is born !

The Flanger

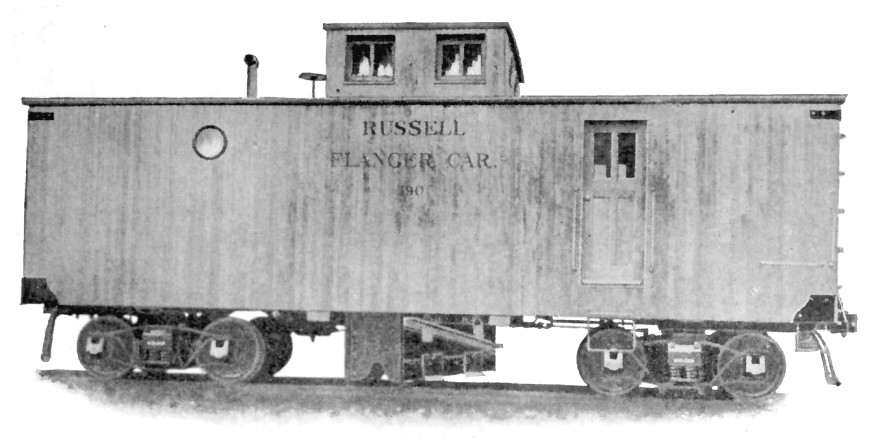

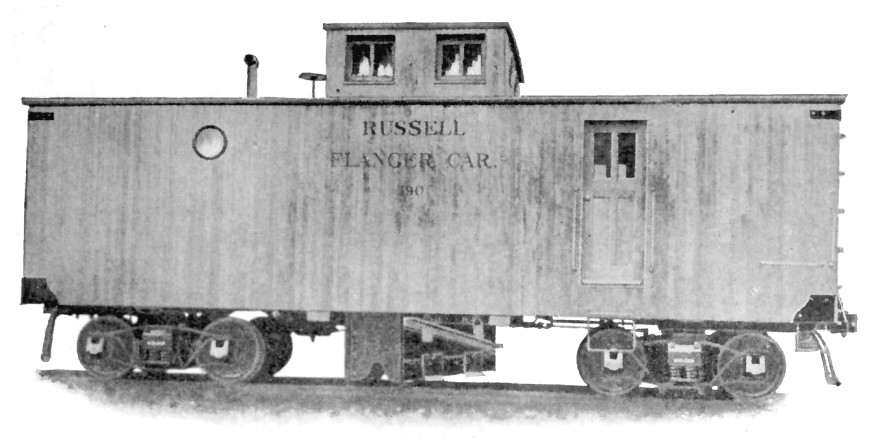

It's a car ... it's an assembly, too ...

While this may look like any old caboose,

you can see extra equipment mounted below the centre of the car.

It is not a caboose, it is a 'Flanger' [car].

The reason for the 'caboose cupola' will become apparent in a minute.

A tiny detail ... plows and flangers can come in 'single track' or 'double track' models.

A 'V' nosed plow works OK on single track.

For double track, you want to dump the snow only on ONE SIDE - like plowing a highway today.

The flanger shown here dumps to to RIGHT side making it a double track model.

While the snow may have been plowed from above the rails,

so trains can run normally after a storm ...

an accumulation of snow and ice within the track structure will

cause damage in the longer term, particularly with repeated freeze and thaw cycles.

The metal flanger [assembly] above fits into the paths the wheel flanges will follow

and also clears excess snow and ice from the ties and ballast.

Usually the Flanger [car] was given additional weight with built-in scrap metal

to ensure it didn't ride up on ice and derail.

HOWEVER,

the flanger assembly is also very very good

at removing everything else from between the rails ...

timbers at level crossings,

switch assemblies,

'guard rails' - the extra track rails laid on bridges,

passenger platform crossings at stations.

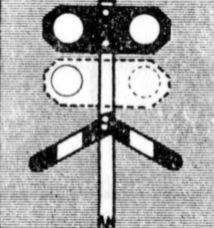

So ... you get someone up in that cupola who knows the road well, usually a senior maintenance of way person ...

to RAISE the flanger assembly

before it removes the hardware which the railway would prefer to leave down there between the rails.

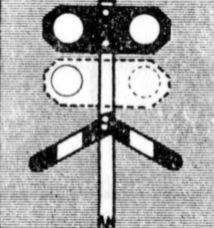

If you have ever noticed the top black and white sign beside the tracks

(two circles on a contrasting board) ...

it is a Canadian-style reminder to 'lift the flangers'.

It is often referred to as a 'snowplow target'.

Plows Built as Separate Cars

Seriously ... who wants to have a big ugly plow thing screwed onto the front of their locomotive all winter ?

Steam locomotives were designed to pull trains ... not to plow with a 'destroyer ramming bow' attached to the cowcatcher.

The railways started to operate larger specialized pieces of rolling stock

which could be quickly coupled on the front of a locomotive or a regular train during a snow storm.

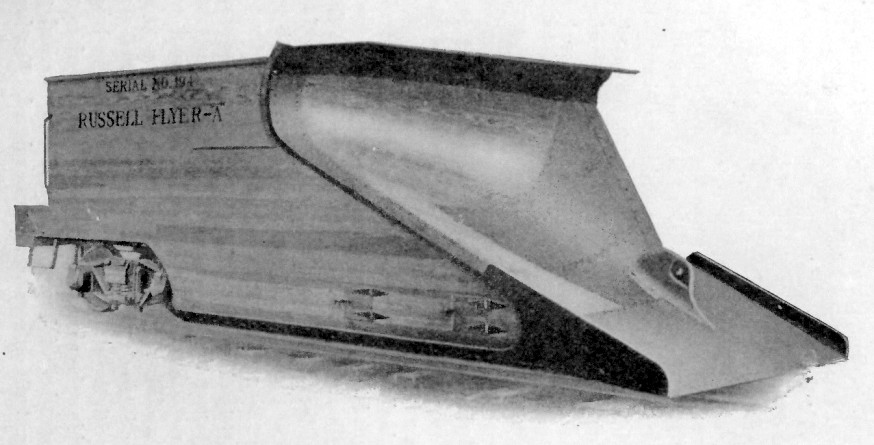

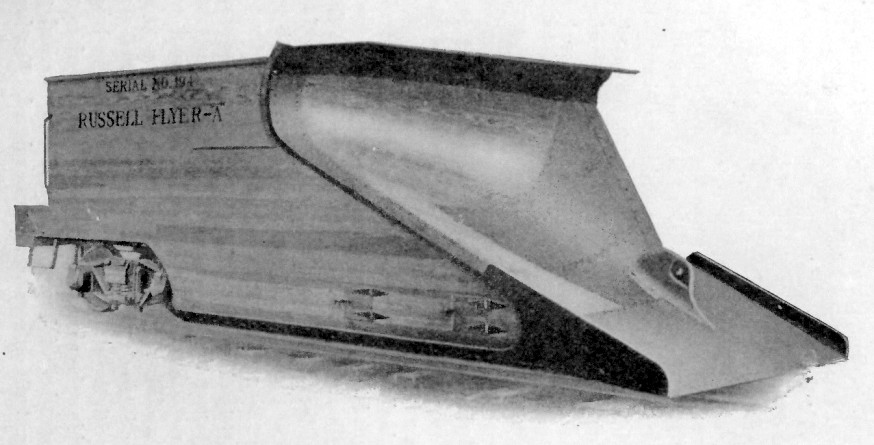

So here is an early version of a 'snow-plough'.

The snow rides up the shovel nose.

When you go faster, the momentum throws the snow clear of the right of way.

Later, be sure to come back with your flanger to tidy up.

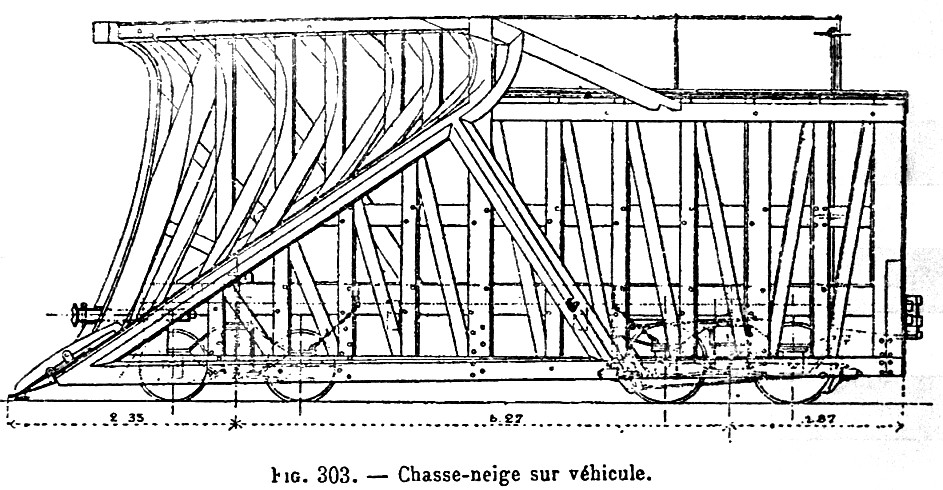

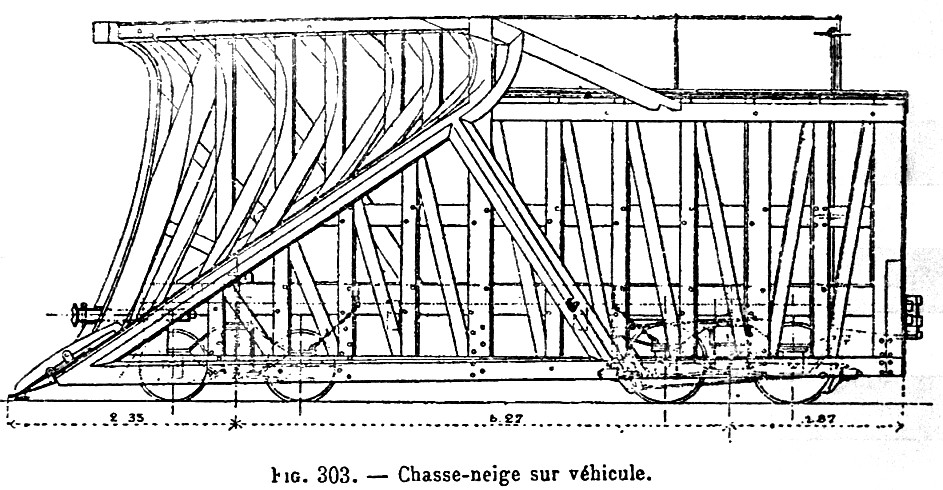

From a comprehensive 1907 railway textbook from France comes this nice view of the internal framework of a snowplow.

It has a flanger ... and a hand brake acting on the rear truck to prevent the car from rolling away on you.

I don't imagine this vehicle was ever built or used in France.

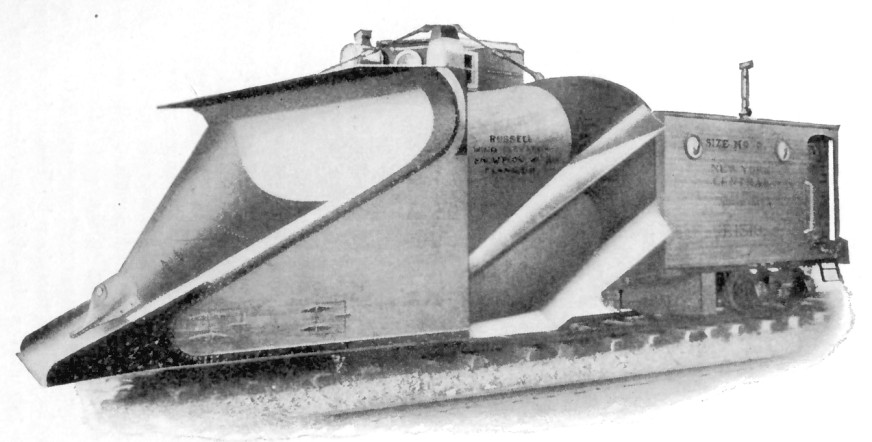

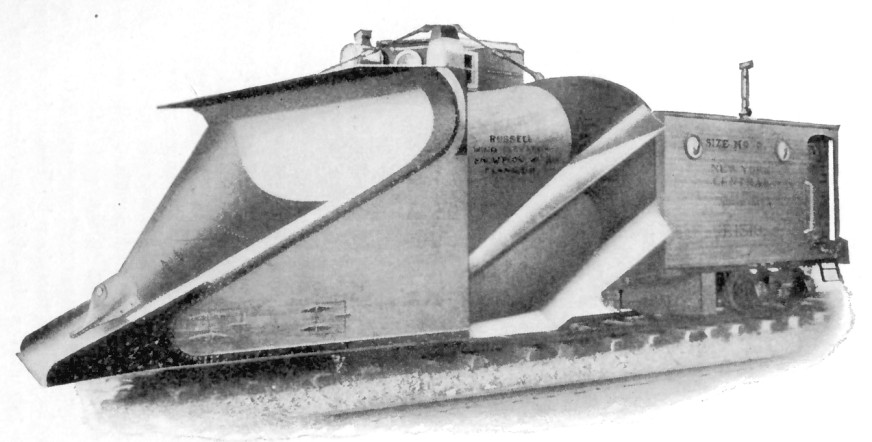

The Russell Plow

The plow that has everything !

A 1915 textbook on winter trackwork gives some good detail on The Russell Plow.

"Probably the best known push plow is the Russell

Plow, which was introduced in Canada in 1885 and used

on the Intercolonial Railway for some years before it

was used to any extent by the railways of the United

States, where it is now operated over many lines. This

plow is a large, well and strongly-built machine. It is

designed for both single and double-track use, and is

built on especially strong trucks and sills. The mid

rib which forms the cutting edge starts 5 ft. or more

back from the nose of the shovel. The weight of snow

carried on top of the shovel is considerable, and the

weight of a drift when the shovel is pushed into and

under it is so great that a special truck is used with journals

on the inside and outside of each wheel to keep the

wheels from running hot. This weight of snow, of

course, also bears on the mid rib which must be made

of a heavy beam of the toughest kind of wood. A special

heavy middle beam or power bar is laid between

the middle sills of the car from end to end, the draw bar

being on the rear end and the front end framed against

the mid rib of the nose of the plow.

"The rear part of the Russell plow is a little narrower

than the front, so that the snow does not crowd so close

as it otherwise would. The doors are at the sides and

rear end, and open into a narrow end room. One inside

door opens from this rear room into the main room

where the wing gears and compressed air cylinders are

set. There is a stove, fuel box and tool box in this room.

A short stairway leads to the cupola or lookout, which

has seats for two, one seat on each side behind a small

lever which controls the movement of the wing. There

are side windows and front port windows in this cupola.

The nose of the shovel, the wings and all parts against

which the snow presses are armored with steel plates,

the outside surfaces being quite smooth. The outside

of the car is made of dressed and matched lumber carefully

planed and varnished so as to be as smooth as possible

to slip through the snow.

"A Russell plow should throw average snow over a

fence 50 ft. from the center line of track when going 50

miles an hour. Such speed is of course not always safe,

especially in hard or old snow where ice may have

formed over the rail. A Russell plow off the track is

usually a serious proposition. In the first place the

opening of the road for traffic depends on the plow's

performance. If derailed, traffic may be held up and the

track department may be powerless to help without the

plow. Again, in snowy weather, re-railing any car is not

easy. The re-railing frogs must be spiked to prevent slipping

and snow must be brushed away at every move to

see what is next to be done. Tools are easily lost in snow

and slippery rails add to the trouble. The Russell plow

sets close to the rail. It is very heavy in front and hard

to get under or to see under unless one can look through

the "peek" doors at the sides of the front truck. The wings

are close to the rail and may be jammed or knocked

loose when the plow is derailed. In fact, great care must

be used when backing a Russell plow around a wye or

over switches on curves to be sure that the heels of the

closed wings do not strike guard rails, crossing plank or

other objects outside the rails. The modern Russell

plow is a big car. It is heavy and hard to re-rail. On

the other hand, it is very strong, and will stand a lot of

hard use without serious harm, if properly handled.

"The Russell plow is made for single-track and for double-track and in various sizes and styles, with and without

compressed air for wings and flanges.

"The single track plow is made to throw snow each

way from the center of the track. Right and left-hand

double-track plows are also made, which throw to one

side only. The power bar of the Russell plow and of all

other first-class push plows has a side play of a few

inches at the rear end to allow for free movement around

curves, the amount depending on length of car and sharpness

of curve. Wood alcohol for freeing window and

port hole glass from frost should always be carried on

a snow plow as well as flags, torpedoes, coal, bell cord,

brooms, snow shovels, picks, axes, bars, spike mauls,

track gage and rail fastenings, lanterns, wicks and

matches."

The same picture again.

The plow with everything.

Notice the extendable wings to throw the snow farther to the side, located beside the operator's cupola.

A flanger assembly box hangs below the first porthole.

Coal stove, recessed entrance door ... sweet.

In front of the cupola is the snowplow's headlight so you can work safely at night.

The angled arms appearing below the 'snowplow target' sign to 'lift flangers' ...

apply to retracting the plow wings.

The operator would be prompted to do this before passing:

signal masts,

stations,

close wayside poles,

rock cuts

and other restricted side clearances.

The sign above warns to retract both the left and right wings.

Canadian Railway Plows

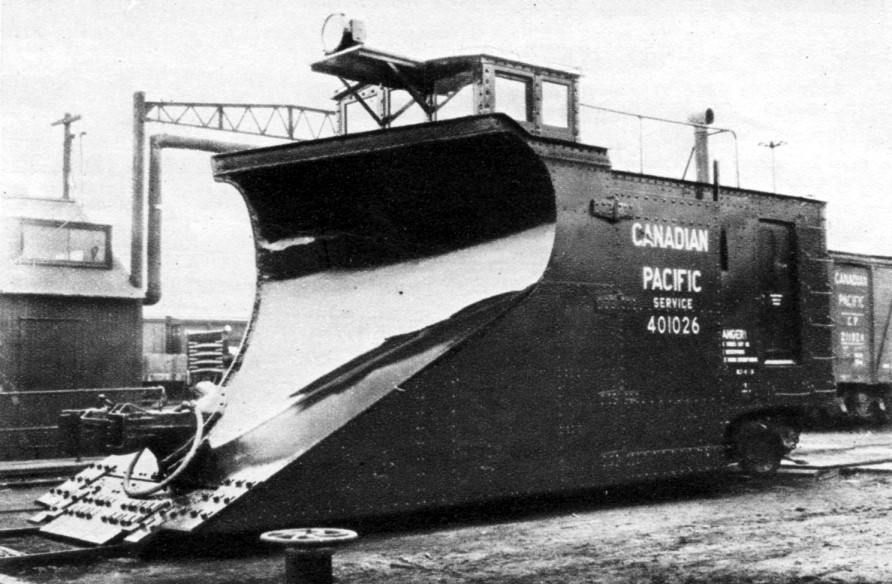

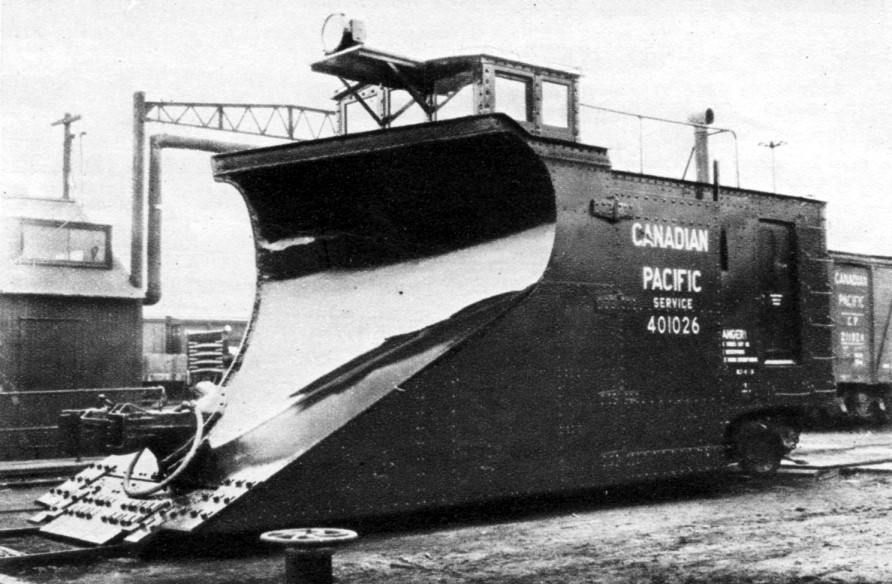

Built by Angus Shops in 1931, this CPR plow has an 'all in one' flanger/plow arrangement like the French diagram ...

The lowered flangers at the front scrape right to the bottom of the snow mass and everything slides up the shovel nose.

'Canadian Pacific' is painted on the extendable wings and you can see the four hinges on which they'd swing out.

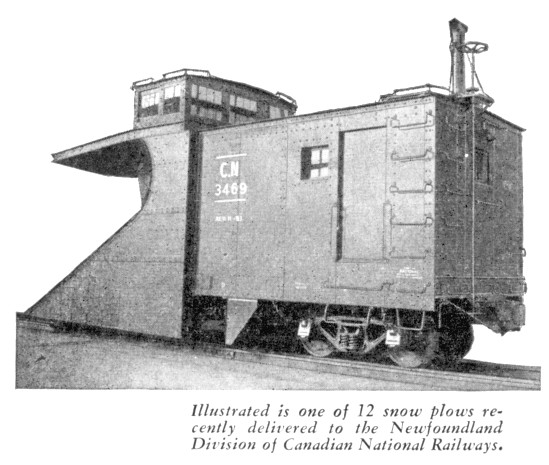

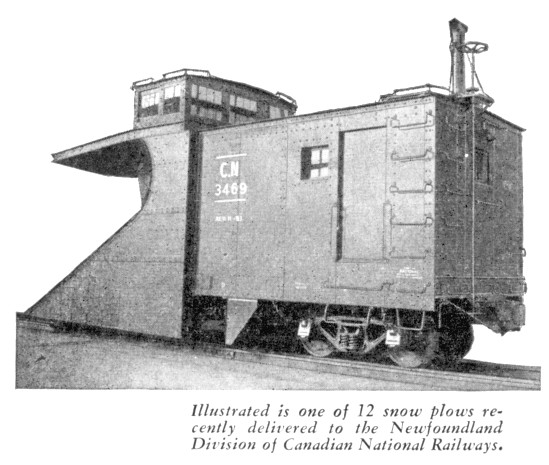

From a 1954 National Steel Car (Hamilton) advertisement ... a new plow for the narrow gauge CNR in Newfoundland.

No fancy wings for Newfoundland.

The flanger seems to be mid-plow.

As part of CNR, just after joining Confederation in 1949, Newfoundland was early to dieselize.

With diesel locomotives and new plows ...

I wonder if this spelled the end for Newfoundland's steam rotary snowploughs.

The Spreader

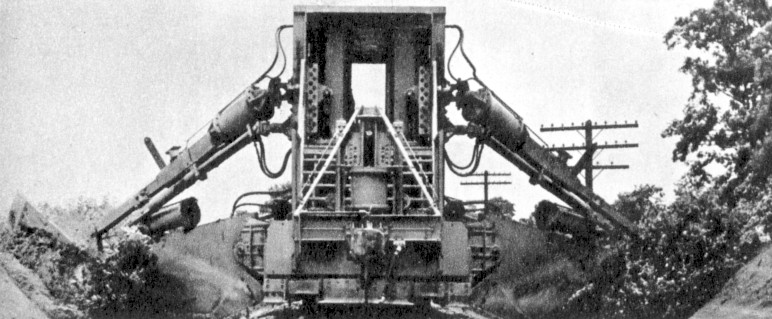

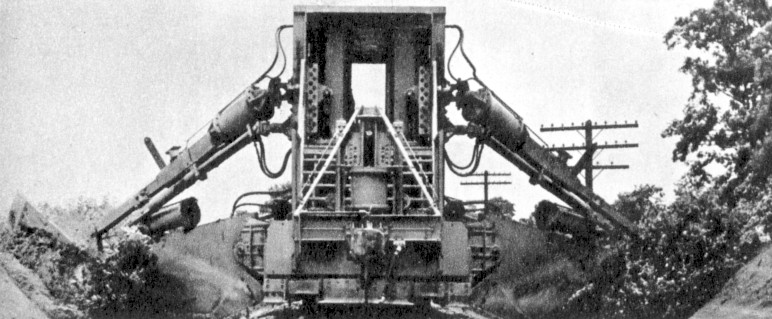

Often referred to as a 'Jordan Spreader' after

one particular builder: O.F. Jordan Inc. of Chicago.

Snowplows using wings can throw snow back quite a distance.

However, the plow must be travelling fast enough to give the snow mass good momentum.

You can't travel at high speed within yards or sidings ...

you can't plow by passenger stations at high speed ...

You need a plow which has the power to move the snow away without the speed.

A 'spreader'.

Powered blades can be positioned to plow,

or they can be moved against a load,

with great flexibility for ...

spreading fresh ballast, plowing snow, or clearing brush to show off.

Like a snowplow, this equipment would be coupled to a locomotive - it is not self-propelled.

Circa 1930 or 1940 a Jordan Spreader on the Northern Pacific has its right wing extended, probably to 'spread' a siding.

It is being propelled by a steam locomotive with a caboose behind - notice the marker on the tailend.

Special promotion: For hours of steam-powered rotary snowplough entertainment

... see 'Newfoundland Part 5' back at the site map.

( ... if you still feel like it ... I'll remind you when you finish this page ... )

A Snowplow in Kingston, Ontario

In early 1982, the 8737 operated a plow extra to Kingston during a snowstorm.

I happened to be standing around, looking north, on the wrong side of the CNR tracks with my camera.

At the treeline is Highway 401, and the Division Street overpass is to the right - out of the picture.

Having just operated south from the CPR mainline at Tichborne, to the CPR interchange at CNR Queens East ...

the consist will be switched for the reverse movement over the former 'Kingston and Pembroke' line.

The documentation on this snapshot which I recently purchased:

"East switch Stephen,

Altitude 5337 feet, highest siding on CPR lines.

18 Jan 1942 1238hr"

The photo is looking down the track toward Calgary from the continental divide of the Rocky Mountains.

In addition to semaphore signals and a kerosene switch lamp,

you can also see evidence of ...

snowplowing with flangers, spreading ...

and good old switch cleaning by hand !

Back to sitemap