Great War battlefield survivors - Part 2

'We support the troops!' ...'til the boys come home."Shell Shock"

In his 1985 book War, Gwynne Dyer wrote:

"The U.S. Army concluded during World War II that almost every soldier,

if he escaped death or wounds, would break down after 200 to 240

'combat days'; the British, who rotated their troops out of the front line more

often,

reckoned 400 days, but they agreed that breakdown was inevitable. The

reason that only about one sixth of the casualties were psychiatric was

that most combat troops did not survive long enough to go to pieces."

Dyer quotes a US investigation from 1946:

"There is no such thing as 'getting

used to combat.' ... Each moment of combat imposes a strain so great

that men will break down in direct relation to the intensity and

duration of their exposure."

* * *

While military commanders employ

the 'fighting system' of 'the men' by using an epidemiological rule of

thumb to avoid collective mental breakdown ... the mental health care professionals

who must deal with the psychological casualties would emphasize that

there

is considerable variation in the tolerance for stress when considering

patients as individuals.

Just as new soldiers have to be trained and conditioned to overcome their evolved human reluctance to kill other people ... we bipedal mammals have not evolved in environments where there were high-stress or combat conditions for hundreds of days within the span of a few years. Our ancient ancestors probably would have won or lost their fights in a short period of time ... or run away across the savannah, or into the jungle.

It is only the evolved intelligence and power of a modern society's principles, combined with emotion-suppressing military discipline ... maybe like cock-fighting enclosures built of ideas ... which could assemble groups of trained, own-species killers in matching costumes (soldiers) ... and force them to live in cold, disease-and-water-filled ditches for weeks on end (the Great War's Western Front).

... And later, the power of modern civilization is even more evident ... after a week or two of rest, and life away from these miserable conditions ... these same humans willingly rotate back to these same ditches, to again be exposed to ... heavy bombardment by high explosive and shrapnel; friends being dismembered or atomized by shells; cold, and exposure to the elements; poor rations; chronic sleep deprivation; large rats eating unearthed corpses and the sleeping and the wounded; disease and parasites; discovering atrocities on civilians; poison gas; strange but deadly orders from British commanders; battlefield errors; etc.

The Great War Western Front epidemic of mental disorders - popularly known as 'shell shock' - was different because it was a significant opportunity for thoughtful, educated humans to reflect on how to treat the health effects of trauma in a large, varied population of patients. (The Germans - being usually more practical about war realities - were generally ahead of the British in helping their soldiers. The French had some good ideas too. The Americans watched from the sidelines and took careful notes)

The clearest English-language Great War era book on 'shell shock' I have found was written by Dr. G. Elliot Smith (British) and was published in May 1917: "Shell Shock and its Lessons". It was deliberately written for a general audience so war leaders and society as a whole could understand why great numbers of soldiers were being disabled by war stresses ... and what could be done to help them.

* * *

It is often stated that 'freedom isn't free', and 'its price is (apparently

denominated in) blood'. However, it is facile to suggest that burials and

bandages are the only human costs politicians need to consider when

they elect to deploy soldiers for 'war-fighting' or high-stress

missions.Just as new soldiers have to be trained and conditioned to overcome their evolved human reluctance to kill other people ... we bipedal mammals have not evolved in environments where there were high-stress or combat conditions for hundreds of days within the span of a few years. Our ancient ancestors probably would have won or lost their fights in a short period of time ... or run away across the savannah, or into the jungle.

It is only the evolved intelligence and power of a modern society's principles, combined with emotion-suppressing military discipline ... maybe like cock-fighting enclosures built of ideas ... which could assemble groups of trained, own-species killers in matching costumes (soldiers) ... and force them to live in cold, disease-and-water-filled ditches for weeks on end (the Great War's Western Front).

... And later, the power of modern civilization is even more evident ... after a week or two of rest, and life away from these miserable conditions ... these same humans willingly rotate back to these same ditches, to again be exposed to ... heavy bombardment by high explosive and shrapnel; friends being dismembered or atomized by shells; cold, and exposure to the elements; poor rations; chronic sleep deprivation; large rats eating unearthed corpses and the sleeping and the wounded; disease and parasites; discovering atrocities on civilians; poison gas; strange but deadly orders from British commanders; battlefield errors; etc.

The point is ... modern warfare just isn't 'natural' ... and it often stresses our variety of mammals beyond its

evolved psychological limits.

The Great War Western Front epidemic of mental disorders - popularly known as 'shell shock' - was different because it was a significant opportunity for thoughtful, educated humans to reflect on how to treat the health effects of trauma in a large, varied population of patients. (The Germans - being usually more practical about war realities - were generally ahead of the British in helping their soldiers. The French had some good ideas too. The Americans watched from the sidelines and took careful notes)

The clearest English-language Great War era book on 'shell shock' I have found was written by Dr. G. Elliot Smith (British) and was published in May 1917: "Shell Shock and its Lessons". It was deliberately written for a general audience so war leaders and society as a whole could understand why great numbers of soldiers were being disabled by war stresses ... and what could be done to help them.

" ... shell-shock involves no new

symptoms or disorders. Every one was known beforehand in civil life. If

by any stretch of the imagination we could speak of a specific variety

of disease called shell-shock, it would be new only in its unusually

great number of ingredients. And the most gratifying truth of all is

that even this hydra-headed monster, if caught young, can be destroyed.

" From the fact that shell-shock includes no new disorders the important inference may be drawn that the medical lessons taught by the war must not be forgotten when peace comes. The civilian should be offered the facilities for cure which have proved such a blessing to the war-stricken soldier."

" From the fact that shell-shock includes no new disorders the important inference may be drawn that the medical lessons taught by the war must not be forgotten when peace comes. The civilian should be offered the facilities for cure which have proved such a blessing to the war-stricken soldier."

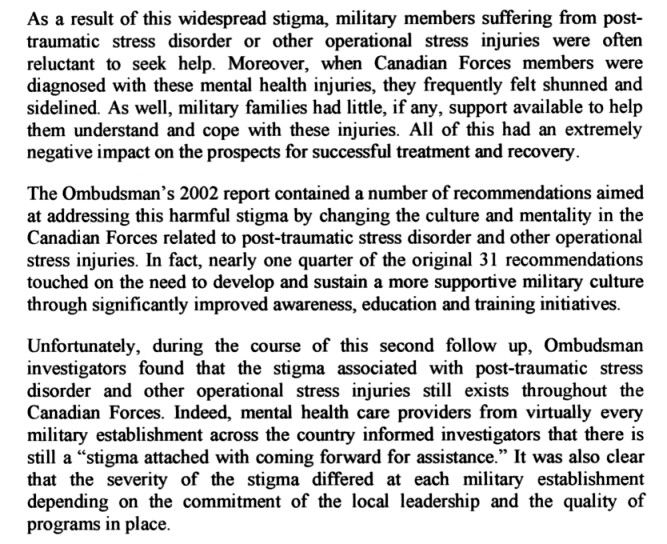

Excerpts from a National Defence 'News Room Backgrounder' on 'Operational Stress'

... from July 2008 provides more details ...

60 years after the American World War 2 retrospective assessment

90 years after 'Shell Shock and its Lessons'

Approximately 85% of Canadian

Forces (CF) personnel returning from deployment will not have to deal

with any mental health issues. The document states that modern terms for

different kinds of Operational Stress are Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder (PTSD) and Operational Stress Injury (OSI). Mental health

screening is one measure taken before a soldier is deployed to try to

predict if the soldier is more prone to a psychological injury.

This is not exclusively a military phenomenon.

"It is caused by an experience in which serious physical harm or death occurred or was threatened. This includes the serious harm or death of a friend or colleague, the viewing or handling of bodies, exposure to a potentially contagious disease or toxic agent, and the witnessing of human degradation (such as sexual assault)."

"PTSD is a complicated disorder with a wide range of symptoms:

If you would prefer to hear some of these symptoms set to music ... you can listen to "Still in Saigon" a 1982 song recorded by the Charlie Daniels Band.

For international visitors to this site ... a Canadian worthy of admiration is retired Canadian Forces Lieutenant General (now Senator) Romeo Dallaire. In late 1993, Dallaire was given command of the United Nations assistance mission to Rwanda. Between April and July 1994, about 1,000,000 Rwandans were killed in an ethnic genocide while General Dallaire was still present and 'responsible' for the minimally-equipped United Nations assistance mission.

The international community was unwilling to upgrade the mission, in spite of General Dallaire's urging, so that hundreds of thousands of lives might have been saved.

He was severely affected by PTSD as a result of the Rwanda mission. In the years that followed, General Dallaire brought public attention to the issue of PTSD by recounting his nearly fatal experiences with the disorder, and by sharing many details of his long course of treatment ... which can be necessary with PTSD.

Personal 'fitness' is a central requirement for a soldier. CBC news reports from the 1990s suggested that soldiers attending psychological counselling for OSI were sometimes labelled as taking 'the walk of shame' by colleagues in the CF - because this was interpreted as a sign of 'weakness'. Dallaire contributed to the necessary, continuing effort to destigmatize soldiers seeking help with this type of injury.

If Romeo Dallaire's experiences suggest that after-action PTSD treatment in the CF culture was inadequate for its general officers ... 20 years after the Americans were writing songs about their Vietnam experiences with it ...

Comparing apples and oranges to get a rough estimate ...

Lectures to 'new grads' in Canada before the Great War

In 1895, a Dr. Daniel Clark gave a series of twelve lectures at the Hospital for the Insane, Toronto, to the graduating medical classes. Some quick quotes from this specialist suggest the extent of psychological knowledge available to 'new grads' to integrate into their professional practice. One would hope, as much as possible, they would also upgrade their knowledge of psychology as new discoveries appeared in medical journals. You would expect that some of these physicians, 20 years later, would be working with patients exposed to the Great War battlefield.

The indented passages come from the 300 page synopsis of the lectures.

Without today's authoritative scientific language of neuron structure and function, neurotransmitters, and 'brain chemistry', Dr. Clark sometimes uses classic literary examples as his authoritative language to assist in the recognition of 'melancholia' ... 'depression' ... one of the disorders we would expect some Great War survivors with PTSD to have to some degree. (It seems unlikely that an injured veteran of the Great War would just have a single health problem ... there would probably be other physical or mental co-morbidities in addition to 'melancholia')

For simplicity, imagine a Canadian or Newfoundland soldier whose ONLY, SINGLE negative wartime experience or injury ... was that he participated in a single traumatic hot-blooded British-style bayonet charge on a German trench. (The terror of the bayonet charge was particularly promoted by the British Army as a tactic to shock disciplined enemy soldiers into individual impulsive personal decisions to surrender ... but this decision was not always duly respected at close quarters in the heat of battle) In our example, some of the enemy had been trying to surrender and the soldier is haunted by what he and the other soldiers did. The killed Germans looked like former store clerks & office workers - not elite Prussian fanatics - and their personal possessions indicated some had families back in Germany. The experienced NCO present didn't shed any tears, and nothing was ever said.

Years later, our bayonet man might be the 'melancholy veteran' who 'never talked about the war and was never the same afterward' ... because, he said, 'some of the things he did could never be forgiven'.

Some nice normal Germans with their pipes and a trench periscope to foil snipers.

'Live and let live' arrangements often existed along the Western Front ...

Warnings were sent before trench mortars were fired.

Trench raids and sniping were not carried out as ordered.

Highlanders shoot, bayonet, club, and drown Germans

at the ancient artificial fishponds at Ermenonville, France.

(A British illustration)

Had the veteran committed a mortal sin not subject to mere medical cures?

Had the veteran committed a socially shameful act as a soldier - which could never be confided to his wife or family?

Could a doctor even understand the veteran's experience ... or effectively treat the depression? What type of treatment? Who would pay for this?

One option was that the veteran could dull the psychological pain by self-medicating with alcohol and perhaps become 'a habitual drunkard' during the Temperance Era.

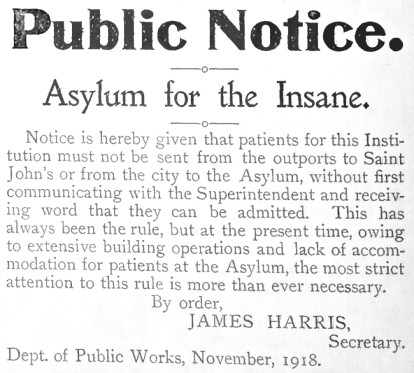

If the soldier was a young officer from a prominent family of considerable reputation ... his relatives might have to accept that there was 'insanity in the family'.

Would they consign him to the 'barbarous regimes of the asylums'?

After the Great War in Canada

An extract from ...

OFFICIAL HISTORY OF THE CANADIAN FORCES IN THE GREAT WAR

1914-19

THE MEDICAL SERVICES

BY

SIR ANDREW MACPHAIL

Kt., O.B.E., B.A., M.D., C.M., LL.D., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., F.R.S.C.

PROFESSOR OF THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE, McGILL UNIVERSITY

PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE MINISTER OF NATIONAL DEFENCE,

UNDER DIRECTION OF THE GENERAL STAFF

Ottawa

F.A. ACLAND

Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty

1925

[Biographical note: MacPhail (1864-1938) was founding editor of the Canadian Medical Association Journal

before he enlisted as a Medical Officer in the Great War, spent four years overseas, and was knighted in 1918]

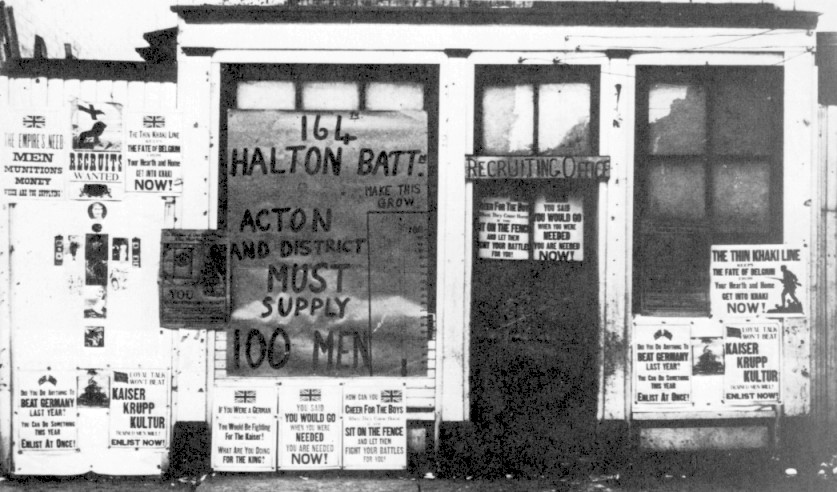

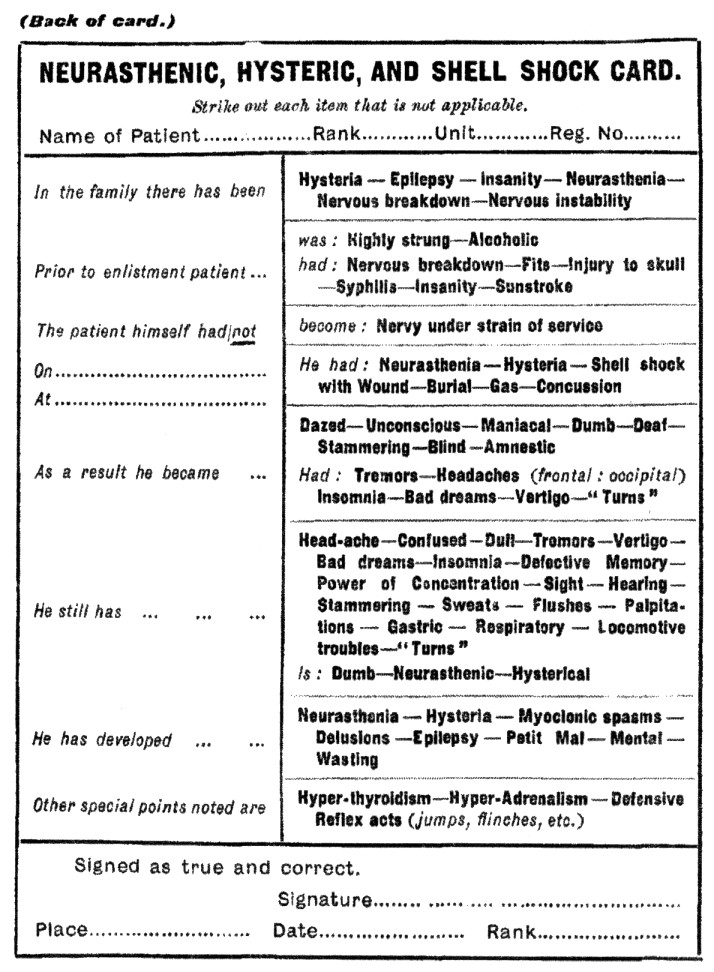

A Canadian recruiting office in 1916 with plenty of 'curb appeal' !

'What are you doing for the King?'

'Sit on the fence and let them fight your battles for you!'

But if guilt makes you enlist ... don't you have MacPhail's aforementioned

"inborn or acquired disposition to emotivity"?

Sir Andrew MacPhail continues with the Official History (1925) ...

The article which follows was published at the end of the Great War. It attempts to interpret and explain veterans' post-war challenges ... and asks the citizens of Newfoundland to understand and be patient with the returning soldiers.

Sir Andew MacPhail, as a military medical doctor (previous excerpt) could not accept the concept of legitimate psychological injuries when he wrote the Official History of the Canadian Medical Services in the Great War ... seven years after the following lay article appeared,

So, at best, medical support for psychological injuries of war must have been 'spotty' or 'luck of the draw'. The need to replace worn prostheses for limb amputees was easier to understand - and much cheaper for the government - than a lengthy course of post-war counselling by a psychiatrist.

Perhaps the only 'counselling experts' available to help after military discharge were clergy.

Would all veterans feel comfortable discussing the source all traumas with all clergy ... even if they could remember and identify them?

Here is the Newfoundland article:

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

This is not exclusively a military phenomenon.

"It is caused by an experience in which serious physical harm or death occurred or was threatened. This includes the serious harm or death of a friend or colleague, the viewing or handling of bodies, exposure to a potentially contagious disease or toxic agent, and the witnessing of human degradation (such as sexual assault)."

"PTSD is a complicated disorder with a wide range of symptoms:

- panic or anxiety (sweating, increased heart rate, muscle tension)

- mood swings, irritability, sadness, anger, guilt, hopelessness and depression

- withdrawal or difficulty expressing emotion; loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities; loss of intimacy

- a preoccupation with the traumatic experience in the form of daydreams, nightmares and flashbacks

- difficulty concentrating, disorientation and memory lapses

- disturbed sleep or excessive alertness (sometimes called hypervigilance)

- erratic behaviour (in an attempt to avoid reminders of the traumatic experience)

- alcohol or substance abuse"

If you would prefer to hear some of these symptoms set to music ... you can listen to "Still in Saigon" a 1982 song recorded by the Charlie Daniels Band.

For international visitors to this site ... a Canadian worthy of admiration is retired Canadian Forces Lieutenant General (now Senator) Romeo Dallaire. In late 1993, Dallaire was given command of the United Nations assistance mission to Rwanda. Between April and July 1994, about 1,000,000 Rwandans were killed in an ethnic genocide while General Dallaire was still present and 'responsible' for the minimally-equipped United Nations assistance mission.

The international community was unwilling to upgrade the mission, in spite of General Dallaire's urging, so that hundreds of thousands of lives might have been saved.

He was severely affected by PTSD as a result of the Rwanda mission. In the years that followed, General Dallaire brought public attention to the issue of PTSD by recounting his nearly fatal experiences with the disorder, and by sharing many details of his long course of treatment ... which can be necessary with PTSD.

Personal 'fitness' is a central requirement for a soldier. CBC news reports from the 1990s suggested that soldiers attending psychological counselling for OSI were sometimes labelled as taking 'the walk of shame' by colleagues in the CF - because this was interpreted as a sign of 'weakness'. Dallaire contributed to the necessary, continuing effort to destigmatize soldiers seeking help with this type of injury.

If Romeo Dallaire's experiences suggest that after-action PTSD treatment in the CF culture was inadequate for its general officers ... 20 years after the Americans were writing songs about their Vietnam experiences with it ...

What was the state of psychological knowledge and care - particularly in the Empire - around the time of the Great War?

What were the chances that Newfoundland and Canadian battlefield survivors received adequate treatment

after they were discharged from the armed forces of the Empire?

What were the chances that Newfoundland and Canadian battlefield survivors received adequate treatment

after they were discharged from the armed forces of the Empire?

* * *

Today the Canadian Forces suggest that 'approximately 85% of CF personnel returning from deployment will not have to deal with any mental health issues'.

The CF statement of today does not specify the length, intensity, or number of 'deployments' in its statement.

During the Great War, for volunteers, 'deployment' was not measured in months ... deployment was 'for the duration' of the war, i.e. consecutive years - with no indication that the war would suddenly stop in November 1918.

In all, 595,441 people enlisted in Canada between the beginning of the Great War and November 1918. Note that this does not include Newfoundland's units.

So of the 418,052 who went overseas ... 59,545 did not survive ... leaving 358,507 who were deployed and who survived the war.Is this really going to be a problem after the Great War?

'Why haven't we heard about it?'

'Why haven't we heard about it?'

Today the Canadian Forces suggest that 'approximately 85% of CF personnel returning from deployment will not have to deal with any mental health issues'.

The CF statement of today does not specify the length, intensity, or number of 'deployments' in its statement.

During the Great War, for volunteers, 'deployment' was not measured in months ... deployment was 'for the duration' of the war, i.e. consecutive years - with no indication that the war would suddenly stop in November 1918.

In all, 595,441 people enlisted in Canada between the beginning of the Great War and November 1918. Note that this does not include Newfoundland's units.

| Killed in action Died of wounds Died of disease Wounded Prisoners of war Presumed dead Missing Deaths in Canada |

35,684 12,437 4,057 155,839 3,049 4,682 398 2,287 |

Comparing apples and oranges to get a rough estimate ...

If '85% won't have to deal with any mental health issues' as they are known today ...

15% or 53,776 Canadian Great War survivors would 'need to deal with [some] mental health issues'

... if you assume their 'deployment experience' was comparable to today's.

15% or 53,776 Canadian Great War survivors would 'need to deal with [some] mental health issues'

... if you assume their 'deployment experience' was comparable to today's.

Newfoundland had approximately 6000 Great War survivors from the Newfoundland Regiment and the Royal Navy Reserve.

Again, using today's Canadian rule of thumb, one could estimate there would be about 900 veterans with some 'mental health issues'.

Again, using today's Canadian rule of thumb, one could estimate there would be about 900 veterans with some 'mental health issues'.

Lectures to 'new grads' in Canada before the Great War

In 1895, a Dr. Daniel Clark gave a series of twelve lectures at the Hospital for the Insane, Toronto, to the graduating medical classes. Some quick quotes from this specialist suggest the extent of psychological knowledge available to 'new grads' to integrate into their professional practice. One would hope, as much as possible, they would also upgrade their knowledge of psychology as new discoveries appeared in medical journals. You would expect that some of these physicians, 20 years later, would be working with patients exposed to the Great War battlefield.

The indented passages come from the 300 page synopsis of the lectures.

"Insanity: Insanity is a fixed

physical disease, which affects and controls abnormally the language,

conduct and natural characteristics of the individual.

"... It is always a physical disease. There is no reason to believe that the entity called mind is ever diseased. If the organ through which it makes itself manifest is in tune, then will the operator be able to healthily make known its normal condition. The medium is at fault, and not the agent. The term physical is used instead of simply brain disease, because in a large class of insane the causes primarily are found in parts of the body outside the skull. We observe this in puerperal insanity, insanity from heart disease, insanity from dyspepsia, or from kidney troubles.

"... The reflexes and their potency in disease are being better understood now-a-days, and in no realm of medicine is a knowledge of them of more importance than in nervous and mental abnormalities.

"Skae's classification is held by many alienists to be the best ... It is too complicated to be practical in the study of the various kinds of insanity. It will be seen, however, it is not entirely aetiological, but is an attempt in that direction.

"It is as follows: [the types are also numbered in the original text ... here we go ...]

general paralysis; paralytic insanity (organic dementia); traumatic insanity; epileptic insanity; syphilitic insanity; alcoholic and toxic insanity; rheumatic and choreic insanity; gouty (podagrous) insanity; phthisical insanity; uterine insanity; ovarian insanity; hysterical insanity; masturbatic insanity; puerperal insanity; lactational insanity; insanity of pregnancy; insanity of puberty; climacteric insanity; senile insanity; anaemic insanity; diabetic insanity; insanity from Bright's Disease; the insanity of oxaluria and phosphaturia; insanity of cyanosis from bronchitis, cardiac disease and asthma; metastatic; post-febrile insanity; insanity from deprivation of the senses; the insanity of myxoedema; the insanity of exophthalmic goitre; the delerium of young children; the insanity of lead poisoning; post-connubial insanity; the pseudo-insanity of somnabulism." [... Do you expect us to know this for the exam and will spelling count?]

"... It is always a physical disease. There is no reason to believe that the entity called mind is ever diseased. If the organ through which it makes itself manifest is in tune, then will the operator be able to healthily make known its normal condition. The medium is at fault, and not the agent. The term physical is used instead of simply brain disease, because in a large class of insane the causes primarily are found in parts of the body outside the skull. We observe this in puerperal insanity, insanity from heart disease, insanity from dyspepsia, or from kidney troubles.

"... The reflexes and their potency in disease are being better understood now-a-days, and in no realm of medicine is a knowledge of them of more importance than in nervous and mental abnormalities.

"Skae's classification is held by many alienists to be the best ... It is too complicated to be practical in the study of the various kinds of insanity. It will be seen, however, it is not entirely aetiological, but is an attempt in that direction.

"It is as follows: [the types are also numbered in the original text ... here we go ...]

general paralysis; paralytic insanity (organic dementia); traumatic insanity; epileptic insanity; syphilitic insanity; alcoholic and toxic insanity; rheumatic and choreic insanity; gouty (podagrous) insanity; phthisical insanity; uterine insanity; ovarian insanity; hysterical insanity; masturbatic insanity; puerperal insanity; lactational insanity; insanity of pregnancy; insanity of puberty; climacteric insanity; senile insanity; anaemic insanity; diabetic insanity; insanity from Bright's Disease; the insanity of oxaluria and phosphaturia; insanity of cyanosis from bronchitis, cardiac disease and asthma; metastatic; post-febrile insanity; insanity from deprivation of the senses; the insanity of myxoedema; the insanity of exophthalmic goitre; the delerium of young children; the insanity of lead poisoning; post-connubial insanity; the pseudo-insanity of somnabulism." [... Do you expect us to know this for the exam and will spelling count?]

Without today's authoritative scientific language of neuron structure and function, neurotransmitters, and 'brain chemistry', Dr. Clark sometimes uses classic literary examples as his authoritative language to assist in the recognition of 'melancholia' ... 'depression' ... one of the disorders we would expect some Great War survivors with PTSD to have to some degree. (It seems unlikely that an injured veteran of the Great War would just have a single health problem ... there would probably be other physical or mental co-morbidities in addition to 'melancholia')

"Melancholia differs chiefly from

dementia in the superaddition to the symptoms of the latter of evidence

of depression of mind. This evidence overshadows all other conditions,

and is paramount in the patient's mind. The sadness stands in the front

of the mental photograph ...

"... [compared to the hypochondriac who is always hopefully searching for a miracle cure] The melancholy man has no such hope. No ray of comfort brightens the gloom of his life. So far from entertaining hopes of recovery or confidence in treatment, he rejects with something like contempt, the advice that is tendered for his welfare.

"Molehills of neglect are magnified into mountains of guilt. To many such melancholy persons these trifles are, in the sum total, "the sin against the Holy Ghost," and, according to the Holy Scriptures, can never be forgiven in this world nor in the world to come.

"Shakespeare, the greatest of the students of nature, penned truthfully of those who are afflicted [with melancholia] as Hamlet was said to be:

Some references suggest that in the Great War era ... mental disease which became serious enough to require the protection of an 'asylum' would generally continue to get worse until the patient's eventual death. Effective treatment and 'cures' were not considered likely.

"... [compared to the hypochondriac who is always hopefully searching for a miracle cure] The melancholy man has no such hope. No ray of comfort brightens the gloom of his life. So far from entertaining hopes of recovery or confidence in treatment, he rejects with something like contempt, the advice that is tendered for his welfare.

"Molehills of neglect are magnified into mountains of guilt. To many such melancholy persons these trifles are, in the sum total, "the sin against the Holy Ghost," and, according to the Holy Scriptures, can never be forgiven in this world nor in the world to come.

"Shakespeare, the greatest of the students of nature, penned truthfully of those who are afflicted [with melancholia] as Hamlet was said to be:

| "His brain is wrecked - For ever in the pauses of his speech His lips doth work with inward mutterings, And his fixed eye is riveted fearfully On something that no other eye can spy. Canst thou minister to a mind diseased? Pluck from the memory & rooted sorrow, Raze out the written troubles of the brain, And with some sweet, oblivious antidote, Cleanse the foul bosom of that Perilous stuff Which weighs upon the heart." |

Some references suggest that in the Great War era ... mental disease which became serious enough to require the protection of an 'asylum' would generally continue to get worse until the patient's eventual death. Effective treatment and 'cures' were not considered likely.

An Simplified Example of a Great War psychological injury ...

For simplicity, imagine a Canadian or Newfoundland soldier whose ONLY, SINGLE negative wartime experience or injury ... was that he participated in a single traumatic hot-blooded British-style bayonet charge on a German trench. (The terror of the bayonet charge was particularly promoted by the British Army as a tactic to shock disciplined enemy soldiers into individual impulsive personal decisions to surrender ... but this decision was not always duly respected at close quarters in the heat of battle) In our example, some of the enemy had been trying to surrender and the soldier is haunted by what he and the other soldiers did. The killed Germans looked like former store clerks & office workers - not elite Prussian fanatics - and their personal possessions indicated some had families back in Germany. The experienced NCO present didn't shed any tears, and nothing was ever said.

Years later, our bayonet man might be the 'melancholy veteran' who 'never talked about the war and was never the same afterward' ... because, he said, 'some of the things he did could never be forgiven'.

Some nice normal Germans with their pipes and a trench periscope to foil snipers.

'Live and let live' arrangements often existed along the Western Front ...

Warnings were sent before trench mortars were fired.

Trench raids and sniping were not carried out as ordered.

Highlanders shoot, bayonet, club, and drown Germans

at the ancient artificial fishponds at Ermenonville, France.

(A British illustration)

What could a medical doctor do for this melancholy veteran? ...

Had the veteran committed a mortal sin not subject to mere medical cures?

Had the veteran committed a socially shameful act as a soldier - which could never be confided to his wife or family?

Could a doctor even understand the veteran's experience ... or effectively treat the depression? What type of treatment? Who would pay for this?

One option was that the veteran could dull the psychological pain by self-medicating with alcohol and perhaps become 'a habitual drunkard' during the Temperance Era.

If the soldier was a young officer from a prominent family of considerable reputation ... his relatives might have to accept that there was 'insanity in the family'.

Would they consign him to the 'barbarous regimes of the asylums'?

Suggestions as to the better treatment of our War Neuroses

Lt.-Col. J. W. Springthorpe, Australian Army Medical Corps

He begins his paper with an interesting summary of four years of war ...

"We entered upon this, the greatest war of all time, with enough of nothing; with the call 'enlist' not 'serve'; with seniority above efficiency; with a machine that followed tradition and compelled delay; with all other claims subordinated to the military; and with a medical profession uninstructed in psychology, and, in most cases, unacquainted with psychopathic manifestations or their proper treatment. Is there any wonder that when we came to deal with the great question of war neuroses we made many and serious mistakes, and that, despite magnificent work in many quarters, very much still continues unsatisfactory, and will so remain until these basal factors are suitable dealt with.

"We have gradually learnt that not only are there not infrequent conditions which can and do seriously upset even the soundest mind in the soundest body, but, also, that people of a recognisable psychopathic constitution, even when not patently unfit to be mobilised for active service, give way sooner or later - generally sooner - under the strain, the infection, the emotional stress, or the unprecedented concussion of this war. We have also come to see that the phases and degrees of disability are so complex that they demand expert differentiation; that many - probably the large majority - of the seriously affected become unequal to a repetition of the strain, and that delayed or unskilful treatment perpetuates many symptoms, and even produces new ones. And we have also found that the number so disabled is exceedingly large, and that the difficulties in the way of their best care and treatment, and of estimating the duration of their disability and degree of their restoration are exceedingly great."

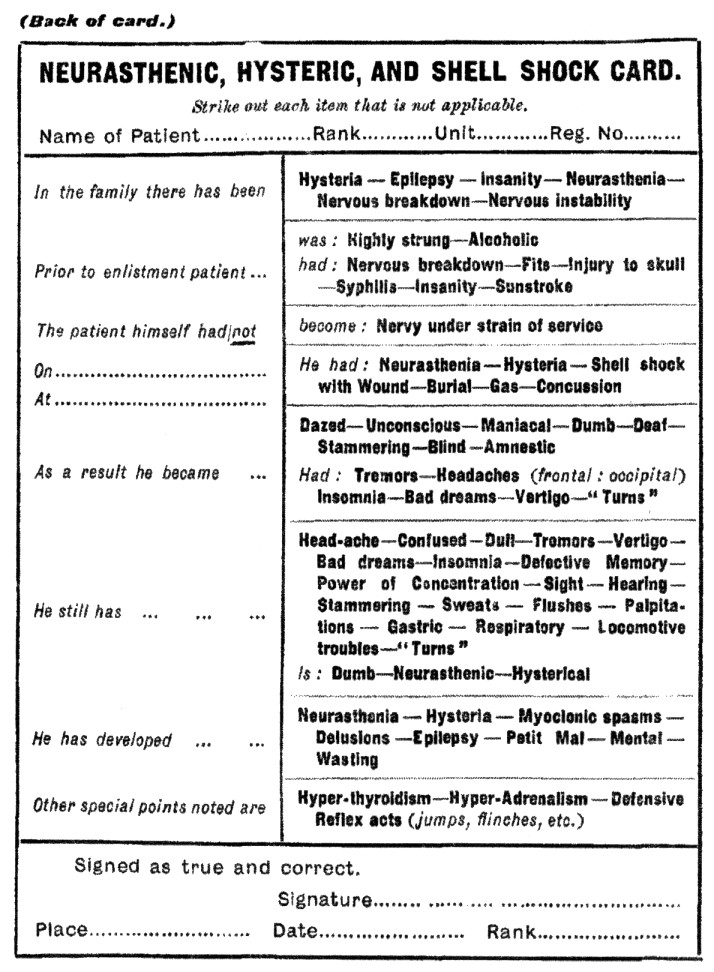

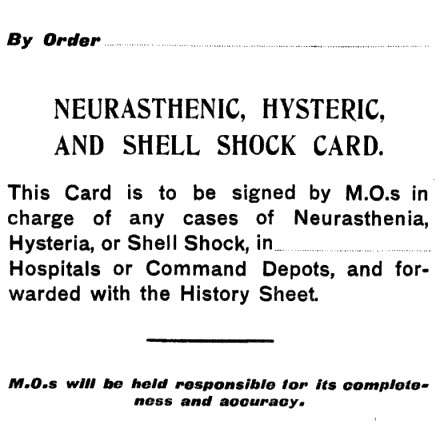

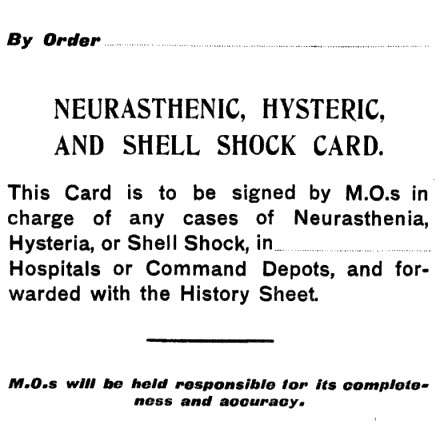

"The Classification which we suggest for general adoption is as follows:

a) The elimination of (1) organic brain conditions (2) the sound but temporarily 'knocked out' and (3) the malingerers, in whom 'the party's criminal will' feigns symptoms that do not exist. Then we have still to discriminate

b) The neurasthenic - where physical strain or infection lights up a psychopathic disposition.

c) The psychasthenic - where psychical strain has upset an allied disposition.

d) The neuromimetic (badly called the hysteric) - with dominant ideas producible, and removable by suggestion.

e) The traumatic - where there has been concussion, local or general, of all degrees of severity, with the usual symptoms.

f) Shell shock - where high explosives have produced a syndrome of symptoms more by emotivity than by commotivity, the latter altering, lessening, and even arresting the characteristic symptoms.

"These varieties may be found separate or combined. Differentiation requires experience and expert knowledge. But it is essential for early and satisfactory treatment. I append a specimen of a card recommended by me for use by the different medical officers concerned."

Lt.-Col. J. W. Springthorpe, Australian Army Medical Corps

Dr. John William Springthorpe (1855-1933) presented a

paper with this title

at the "Inter-Allied Conference on the After-Care of Disabled Men"

held in London in May 1918.

at the "Inter-Allied Conference on the After-Care of Disabled Men"

held in London in May 1918.

J.W. Springthorpe was born in England, but educated in Australia.

He joined the Victorian (i.e. Victoria, the Australian State) Lunacy

Department in

1879 as a junior medical officer. Known as 'Springy' for his short

stature and dynamic activity, he wrote textbooks; worked as a

pathologist, and also studied under Robert Koch, the bacteriologist, in Berlin in 1891;

and practiced medicine in Australia and England. He was a long-time

advocate of mental health issues and actively lobbied for reform.

Working as a medical officer throughout the Great War, it was after

leaving Egypt in 1916 that he turned his attention to studying and

treating 'war neuroses' in England. Back in Australia, he continued to

treat soldiers for years after his military discharge in 1919.

He begins his paper with an interesting summary of four years of war ...

"We entered upon this, the greatest war of all time, with enough of nothing; with the call 'enlist' not 'serve'; with seniority above efficiency; with a machine that followed tradition and compelled delay; with all other claims subordinated to the military; and with a medical profession uninstructed in psychology, and, in most cases, unacquainted with psychopathic manifestations or their proper treatment. Is there any wonder that when we came to deal with the great question of war neuroses we made many and serious mistakes, and that, despite magnificent work in many quarters, very much still continues unsatisfactory, and will so remain until these basal factors are suitable dealt with.

"We have gradually learnt that not only are there not infrequent conditions which can and do seriously upset even the soundest mind in the soundest body, but, also, that people of a recognisable psychopathic constitution, even when not patently unfit to be mobilised for active service, give way sooner or later - generally sooner - under the strain, the infection, the emotional stress, or the unprecedented concussion of this war. We have also come to see that the phases and degrees of disability are so complex that they demand expert differentiation; that many - probably the large majority - of the seriously affected become unequal to a repetition of the strain, and that delayed or unskilful treatment perpetuates many symptoms, and even produces new ones. And we have also found that the number so disabled is exceedingly large, and that the difficulties in the way of their best care and treatment, and of estimating the duration of their disability and degree of their restoration are exceedingly great."

His paper continues with ten points.

Point number 9 is interesting as it presents his proposed classification system and some details of wartime conditions ...

"The Classification which we suggest for general adoption is as follows:

a) The elimination of (1) organic brain conditions (2) the sound but temporarily 'knocked out' and (3) the malingerers, in whom 'the party's criminal will' feigns symptoms that do not exist. Then we have still to discriminate

b) The neurasthenic - where physical strain or infection lights up a psychopathic disposition.

c) The psychasthenic - where psychical strain has upset an allied disposition.

d) The neuromimetic (badly called the hysteric) - with dominant ideas producible, and removable by suggestion.

e) The traumatic - where there has been concussion, local or general, of all degrees of severity, with the usual symptoms.

f) Shell shock - where high explosives have produced a syndrome of symptoms more by emotivity than by commotivity, the latter altering, lessening, and even arresting the characteristic symptoms.

"These varieties may be found separate or combined. Differentiation requires experience and expert knowledge. But it is essential for early and satisfactory treatment. I append a specimen of a card recommended by me for use by the different medical officers concerned."

The card seems designed to provide

the often missing medical history ... from the injured soldier's

originating unit where he was known before the injury. When the soldier

reached a specialized 'war neuroses' hospital, proper formal

classification and specific treatment could then take place.

Dr. Springthorpe thought that a disability pension - like all other pensions - was a statutory right and 'not a mere grant'. He thought the pension values should generally be higher and more consistently awarded for some difficult to treat 'war neuroses'. He suggested that many patients were being rushed through with limited treatment - and retaining their symptoms when they were discharged from the military hospitals.

As CAMC's Colonel Bruce suggested back on this website's "Great War Battlefield Survivors, Part 1" ... it's hard to accurately calculate a pension if proper medical records have not been kept. Furthermore, psychological injuries weren't as obvious and well-understood as ... limb amputations ... when a Pension Board was reviewing a pensionable file with a veteran.

Springthorpe considered 'reconstruction' of the patient as the primary objective, and pensions a relative 'side issue'.

Dr. Springthorpe thought that a disability pension - like all other pensions - was a statutory right and 'not a mere grant'. He thought the pension values should generally be higher and more consistently awarded for some difficult to treat 'war neuroses'. He suggested that many patients were being rushed through with limited treatment - and retaining their symptoms when they were discharged from the military hospitals.

As CAMC's Colonel Bruce suggested back on this website's "Great War Battlefield Survivors, Part 1" ... it's hard to accurately calculate a pension if proper medical records have not been kept. Furthermore, psychological injuries weren't as obvious and well-understood as ... limb amputations ... when a Pension Board was reviewing a pensionable file with a veteran.

Springthorpe considered 'reconstruction' of the patient as the primary objective, and pensions a relative 'side issue'.

After the Great War in Canada

An extract from ...

OFFICIAL HISTORY OF THE CANADIAN FORCES IN THE GREAT WAR

1914-19

THE MEDICAL SERVICES

BY

SIR ANDREW MACPHAIL

Kt., O.B.E., B.A., M.D., C.M., LL.D., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., F.R.S.C.

PROFESSOR OF THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE, McGILL UNIVERSITY

PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE MINISTER OF NATIONAL DEFENCE,

UNDER DIRECTION OF THE GENERAL STAFF

Ottawa

F.A. ACLAND

Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty

1925

[Biographical note: MacPhail (1864-1938) was founding editor of the Canadian Medical Association Journal

before he enlisted as a Medical Officer in the Great War, spent four years overseas, and was knighted in 1918]

"Shell-shock was a term used in the early days to describe a

variety of

conditions ranging from cowardice to maniacal insanity. After endless

discussion the physicians and metaphysicians, the psychologists,

physiologists, and neurologists invented a series of names which did

not leave the matter much clearer than it was when they found it. 'The

war produced no new nervous disease; it was the same hysteria and

neurasthenia neurologists knew before the war,' but it produced many

new names and theories. The condition was well known to the Duke of

Wellington, and he had a routine method of treatment.

"The War Office went so far as to recognize three forms of neurosis or psychoneurosis, namely, shell-shock, hysteria, and neurasthenia. Sir Frederick Mott observed, however, that all persons so affected 'had an inborn or acquired disposition to emotivity.' A similar observation was frequently made by experienced corporals, but they did not record their 'findings' in quite those terms. Soldiers who developed these manifestations in the stress of war would have presented a similar spectacle in corresponding circumstances in civil life. The Americans were so informed. They refused to enlist men who were mentally unstable. From one division alone in progress of formation they eliminated 400 men, and sent 500 more to non-combatant units, with the result that of those who did develop a neurosis only one per cent required to be evacuated."

"The War Office went so far as to recognize three forms of neurosis or psychoneurosis, namely, shell-shock, hysteria, and neurasthenia. Sir Frederick Mott observed, however, that all persons so affected 'had an inborn or acquired disposition to emotivity.' A similar observation was frequently made by experienced corporals, but they did not record their 'findings' in quite those terms. Soldiers who developed these manifestations in the stress of war would have presented a similar spectacle in corresponding circumstances in civil life. The Americans were so informed. They refused to enlist men who were mentally unstable. From one division alone in progress of formation they eliminated 400 men, and sent 500 more to non-combatant units, with the result that of those who did develop a neurosis only one per cent required to be evacuated."

A Canadian recruiting office in 1916 with plenty of 'curb appeal' !

'What are you doing for the King?'

'Sit on the fence and let them fight your battles for you!'

But if guilt makes you enlist ... don't you have MacPhail's aforementioned

"inborn or acquired disposition to emotivity"?

Sir Andrew MacPhail continues with the Official History (1925) ...

"The medical officer at the front had no knowledge of the jargon in

which the problem was being discussed. He could not distinguish

hypo-emotive from hyper-emotive, or commotio cerebri from emotio

cerebri; he could not tell who was right

about certain symptoms, Babinski, Claude, or Roussy, with their

respective reflexes, dynamogenic, and dysocinetic explanations.

'Rheumatism' he knew, a slacker he was pretty sure of after

consultation with the sergeant-major. All violent cases he classified

in his own mind as 'crazy' and sent them to a 'special centre' as 'not

yet diagnosed.'

"They alone jest at scars, who never felt a wound. The best of soldiers after several years service had moments of misgiving, lest in some supreme trial they might behave themselves unseemly 'anxiety neurosis,' it was called. At such times were born those most intimate confidences of the war; and there are many who will always remember a firm and friendly word of assurance, and possibly a draught of rum, from an experienced medical officer whose own hour of 'fear-emotion' had passed.

"Under cover of these vague and mysterious symptoms the malingerer found refuge, and impressed a stigma upon those who were suffering from a real malady. The medical officer was bewildered in his attempt to hold the balance between injustice to the individual and disregard for the needs of the service. Especially was he haunted with a dreadful fear when he was called upon to certify that a man was 'fit' to undergo punishment for a 'crime,' and most especially when it was his duty to be present alone with minister or priest to certify that the award of a courtmartial for cowardice in the face of the enemy, confirmed by the Commander, had been finally bestowed. This attendance at executions was the most painful duty of the medical officers many unpleasant duties.

"The general statement is probably correct, that in the early days of the war too lenient a treatment was accorded to soldiers suffering, thinking they suffered, or pretending to suffer, from concussion or fright neurosis, from hysteria, neurasthenia, psychasthenia, reflex paralysis, katatonic stupor, or combination and subdivision thereof; and that up to the end it was not sufficiently realized that men who were liable to such condition were not fit for the hard business of war. In the summer of 1915, and even of 1916, it was a common spectacle a soldier with no apparent wound or scar, sitting in the shade of an English tree with his pipe and paper, contemplating his misery and reflecting aloud upon his prowess.

"What was once a disease had in 1917 become a stigma, and yet, as one nail drives out one nail and one fire one fire, so fear of the ostracism of contempt for weakness at best and cowardice at worst did much to counteract the emotion of fear of the enemy. "In no circumstances what ever," the order ran, "will the expression 'shell-shock' be made use of verbally or be recorded in any regimental or other casualty report, or in any hospital or other medical document except in cases so classified by the order of the officer commanding the special hospital for such cases."

"The treatment of these cases by suggestion, hypnotism, and 'analysis' was sometimes brilliant, but the results were often short-lived, and the patients soon sought centres for a fresh cure. Dr. L. R. Yealland whose advice was often sought by the Canadian service treated many cases with amazing success at Queen Square Hospital. Hysteria is the most epidemical of all diseases, and too obvious special facilities for treatment encouraged its development. 'Shell-shock' is a manifestation of childishness and femininity. Against such there is no remedy.

SELF-INFLICTED WOUNDS

"Closely allied with this mental state is the desire for self-inflicted wounds. In the Canadian army there is a record of 729 cases of self-inflicted wounds of which 6 were amongst officers. The sufferer was always put under arrest by the first medical officer to whom he applied, and he was sent to a special hospital which had a permanent court-martial in attendance. Each case was considered on its merits, and those were released in which the injury was obviously inflicted by accident and not by design. This rule of arrest was so rigid that a man who, for example, tore his hand upon a wire entanglement would nurse his wound in secret."

"They alone jest at scars, who never felt a wound. The best of soldiers after several years service had moments of misgiving, lest in some supreme trial they might behave themselves unseemly 'anxiety neurosis,' it was called. At such times were born those most intimate confidences of the war; and there are many who will always remember a firm and friendly word of assurance, and possibly a draught of rum, from an experienced medical officer whose own hour of 'fear-emotion' had passed.

"Under cover of these vague and mysterious symptoms the malingerer found refuge, and impressed a stigma upon those who were suffering from a real malady. The medical officer was bewildered in his attempt to hold the balance between injustice to the individual and disregard for the needs of the service. Especially was he haunted with a dreadful fear when he was called upon to certify that a man was 'fit' to undergo punishment for a 'crime,' and most especially when it was his duty to be present alone with minister or priest to certify that the award of a courtmartial for cowardice in the face of the enemy, confirmed by the Commander, had been finally bestowed. This attendance at executions was the most painful duty of the medical officers many unpleasant duties.

"The general statement is probably correct, that in the early days of the war too lenient a treatment was accorded to soldiers suffering, thinking they suffered, or pretending to suffer, from concussion or fright neurosis, from hysteria, neurasthenia, psychasthenia, reflex paralysis, katatonic stupor, or combination and subdivision thereof; and that up to the end it was not sufficiently realized that men who were liable to such condition were not fit for the hard business of war. In the summer of 1915, and even of 1916, it was a common spectacle a soldier with no apparent wound or scar, sitting in the shade of an English tree with his pipe and paper, contemplating his misery and reflecting aloud upon his prowess.

"What was once a disease had in 1917 become a stigma, and yet, as one nail drives out one nail and one fire one fire, so fear of the ostracism of contempt for weakness at best and cowardice at worst did much to counteract the emotion of fear of the enemy. "In no circumstances what ever," the order ran, "will the expression 'shell-shock' be made use of verbally or be recorded in any regimental or other casualty report, or in any hospital or other medical document except in cases so classified by the order of the officer commanding the special hospital for such cases."

"The treatment of these cases by suggestion, hypnotism, and 'analysis' was sometimes brilliant, but the results were often short-lived, and the patients soon sought centres for a fresh cure. Dr. L. R. Yealland whose advice was often sought by the Canadian service treated many cases with amazing success at Queen Square Hospital. Hysteria is the most epidemical of all diseases, and too obvious special facilities for treatment encouraged its development. 'Shell-shock' is a manifestation of childishness and femininity. Against such there is no remedy.

SELF-INFLICTED WOUNDS

"Closely allied with this mental state is the desire for self-inflicted wounds. In the Canadian army there is a record of 729 cases of self-inflicted wounds of which 6 were amongst officers. The sufferer was always put under arrest by the first medical officer to whom he applied, and he was sent to a special hospital which had a permanent court-martial in attendance. Each case was considered on its merits, and those were released in which the injury was obviously inflicted by accident and not by design. This rule of arrest was so rigid that a man who, for example, tore his hand upon a wire entanglement would nurse his wound in secret."

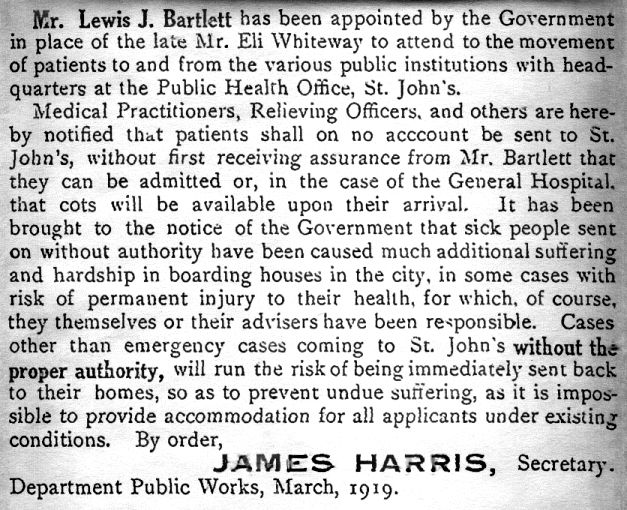

The article which follows was published at the end of the Great War. It attempts to interpret and explain veterans' post-war challenges ... and asks the citizens of Newfoundland to understand and be patient with the returning soldiers.

Sir Andew MacPhail, as a military medical doctor (previous excerpt) could not accept the concept of legitimate psychological injuries when he wrote the Official History of the Canadian Medical Services in the Great War ... seven years after the following lay article appeared,

So, at best, medical support for psychological injuries of war must have been 'spotty' or 'luck of the draw'. The need to replace worn prostheses for limb amputees was easier to understand - and much cheaper for the government - than a lengthy course of post-war counselling by a psychiatrist.

Perhaps the only 'counselling experts' available to help after military discharge were clergy.

Would all veterans feel comfortable discussing the source all traumas with all clergy ... even if they could remember and identify them?

Here is the Newfoundland article: