England and Belgium

Many, many people wrote books about their

experiences

in the Great War. As a war industry, it was probably out-grossed only by artillery shell production.

In England and North America ... and other places that took to book-learnin' ... people were eager to find out the exciting and terrible facts from people who had been there. In some cases, letters home were published posthumously while the war was still on. While letters did not have the same continuity and flow of an account written at a later date, they did chronicle the daily experiences, perceptions, and moods of the author.

Mary Dexter was born in 1886 in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Her letters to her mother were edited and published by her mother - named only as ... 'her mother' (actually Emily Loud Sanford) in October 1918 as "In the Soldier's Service". A few more biographical notes appear at the end of the second page of "Mary Dexter's War" on this website.

"In the Soldier's Service" is divided into the following chapters: England, Belgium, Psycho-Analysis, France ( ' I'll try "Not A Country" for 1000, Alex ' ) There is no preface or further writing by Mary Dexter and one wonders to what extent she was involved in the decision to publish.

Dexter took a camera with her and a few of her many photos are included in the book. She presents a fresh, articulate, non-military perspective of the war and the people involved in it. She records an interesting and diverse variety of wartime patient care environments.

In England and North America ... and other places that took to book-learnin' ... people were eager to find out the exciting and terrible facts from people who had been there. In some cases, letters home were published posthumously while the war was still on. While letters did not have the same continuity and flow of an account written at a later date, they did chronicle the daily experiences, perceptions, and moods of the author.

Mary Dexter was born in 1886 in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Her letters to her mother were edited and published by her mother - named only as ... 'her mother' (actually Emily Loud Sanford) in October 1918 as "In the Soldier's Service". A few more biographical notes appear at the end of the second page of "Mary Dexter's War" on this website.

"In the Soldier's Service" is divided into the following chapters: England, Belgium, Psycho-Analysis, France ( ' I'll try "Not A Country" for 1000, Alex ' ) There is no preface or further writing by Mary Dexter and one wonders to what extent she was involved in the decision to publish.

Dexter took a camera with her and a few of her many photos are included in the book. She presents a fresh, articulate, non-military perspective of the war and the people involved in it. She records an interesting and diverse variety of wartime patient care environments.

American Women's War Hospital, Paignton, England

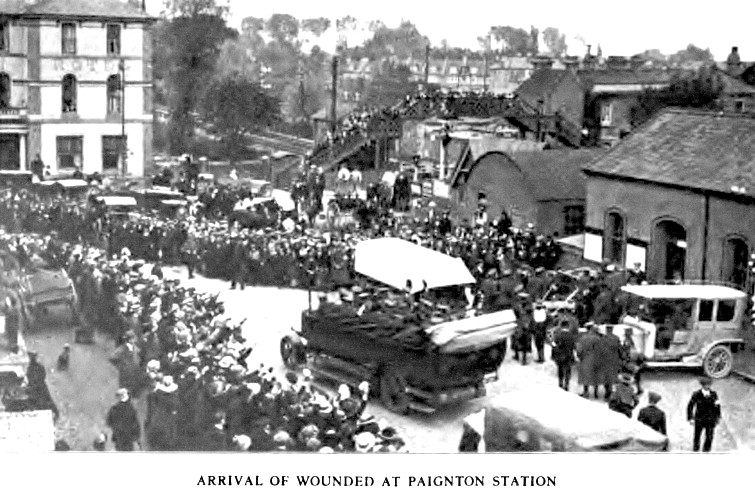

On September 17, 1914 almost immediately after the war began, Mary Dexter was volunteering as meal preparer, then a 'probationer' (assisting nurses) with the British Red Cross in the American Women's War Hospital in Paignton, South Devon. The hospital was located in the Oldway House - the palatial mansion of the Singer (sewing machine) family which today is preserved and publicly owned.

Paignton is near Torquay on the south coast of England ... to the left on this 1923 map.

After being triaged and receiving some treatment in France,

serious British casualties would be brought by ship from France across the Channel.

In this case, ambulance trains met the hospital ships at Southampton (near Portsmouth) ...

and those destined for Paignton then road the rails west.

This was the first major war in which air power was used.

Before long, Dexter reported German aircraft were crossing the Channel,

and Paignton was one of the targets hit along the coast.

Dexter applied herself to the simple work first assigned to her and obtained greater responsibility as she demonstrated her abilities. Her ultimate goal was to care for the wounded at 'The Front'. In fact ... until she was eventually talked out of it ... her long-term objective was to work in Serbia where she felt the need was greatest. She was never paid for her work at the hospital, but she seemed to have no problem with money. She was often soliciting funds for patient supplies through her mother.

As her wartime experience developed, she make good use of 'introductions' by the many people she knew, and at one point used the US Ambassador to France as a reference.

In one letter, she hinted at her family's social status by telling her mother about acquaintances who were 'hard hit' ...

"The T's are hard hit by the war, as is every one. They are closing

three quarters of Old Place, and sending away the cook - the

kitchen-maid is to cook with the scullery-maid to help. Their

menservants are all gone - chauffeur and gardeners as well."

In another case, a patient stated his deductions ...

"Brown is trying to place me. When Sister Vera and I were talking about

going to the front, he was terribly interested whether I had ever put

up with roughing it - said he could not see me traveling three days in

a cattle truck full of wounded. Nevertheless, I said I had

roughed it, and quick as a flash, he said, "How, in a

first-class

carriage?" He ended up by informing me he knew I was a 'pukka' lady.

'Pukka' as I wrote you, means 'real' - the men have picked it up in

India."

Mary Dexter's first Great War work experience was nursing the enlisted soldiers who were remnants of Britain's small professional army - as the Indian reference suggests. Before Kitchener's mass volunteer citizen armies were established, it was a small professional 'British Expeditionary Force' which helped the French save Paris. The BEF was 85,000 experienced officers and men sent over to France within two weeks of war being declared.

The Old Army emphasized regular rifle marksmanship qualification and the the BEF's stand at Mons and its subsequent southbound fighting retreat was probably the last great display of the power of concentrated rifle fire. At this point, the British military establishment did not really believe in machine guns - but change would come.

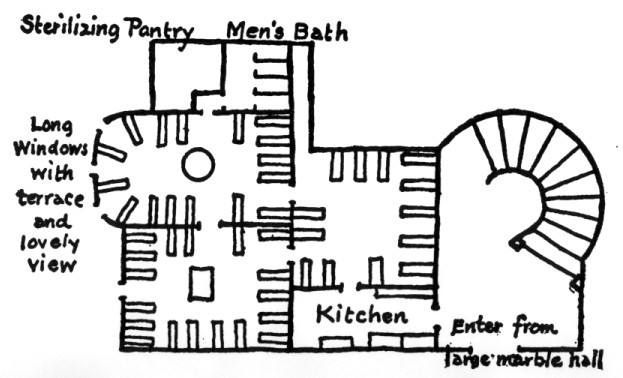

I love what you've done with the place ... converting a mansion into a hospital.

Each room was a separate ward with its own nursing staff - the beds are drawn in.

I am quoting some of Mary Dexter's nursing experiences at length for four reasons:

To quickly introduce Dexter as a motivated care-giver during the Great War, and to establish her credibility as an observer.

To consider her excellent historical detail of the Great War conditions experienced by health care workers and soldiers ... and of the type of care which was given before antibiotics, plastics and disposables. As an example, in most cases cloth bandages were sterilized and re-used.

To show that some aspects of ward nursing never change - such as the relative quiet of a night shift, with its morning rush at the end.

Finally, on the theme of 'battlefield survivors' ...

A good number of any war's 'casualties' - by the military definition - are survivors ... who are changed forever by war. We solemnly remember those who 'gave their lives' and imagine their deaths in battle as the greatest sacrifices possible. Politicians and senior military officers through history have framed it this way ...

Our War = black and white fight for 'freedom'

Soldier's Sacrifice = 'death'

Simple.

Soldier's Sacrifice = 'death'

Simple.

The battlefield survivors (counting

only 'the wounded' of the Great War) greatly outnumber the dead and

defy 'simplicity' when it comes to describing them. Many Canadian world

war

veterans were housed away from public view in special 'nursing home'

hospitals for veterans.

During my own school days in the 1960s, a Grade 5 teacher told us there were veterans seriously disabled by Great War injuries including poison gas just 'down the road'. However, on Remembrance Day, it was only the relatively healthy ambulatory veterans who paraded in the cold. Mary Dexter's account helps us imagine the return to civilian life of the Great War survivors she describes.

During my own school days in the 1960s, a Grade 5 teacher told us there were veterans seriously disabled by Great War injuries including poison gas just 'down the road'. However, on Remembrance Day, it was only the relatively healthy ambulatory veterans who paraded in the cold. Mary Dexter's account helps us imagine the return to civilian life of the Great War survivors she describes.

October 1, 1914 - 130 wounded had arrived by ambulance train

" ... some had lain ten days in the trenches, and many had not washed for six or seven weeks ... "

October 5, 1914

" Another terribly bad case is a nice, fair-haired boy whose arm is all torn away by a shell. He never stops bantering, and keeps the ward in a roar of laughter while his arm is being dressed, although his lips and the cords in his neck are twitching incessantly with pain [...] this boy can't move. He is all day with his arm on pillows and never utters a complaint."

October 23, 1914

" Last week we got a hundred and forty by ambulance train - very bad cases. But they were not in the same filthy, exhausted condition as our first lot of patients ... A bad arm had to be operated on - they did it in the ward instead of taking him to the operating room - screened in, of course. I am fond of the boy, and was glad the operation took place while I was on duty. He is the boy who lay three days in the trenches with a dead man beside him before he was found, and flies got at his wound. If I could stand that operation, I could stand anything. I was holding it and it was all I could bear - the stench was beyond words."

November, 1914

" Mornings, I work especially under Sister Vera in Churchill [Ward], and she is teaching me a lot. She is one of the nurses from Australia, with splendid training - is very strict and gives me the real thing and a liberal supply of pepper which wakens one up! She says I have improved and gives me a lot to do which probationers are not supposed to do at all."

November 16, 1914

On the 20hr to 08hr night shift:

" ... there are only two night nurses for the thirty men of our wards. There is a lovely big coal fire going all night in Burns Ward, which is named for Mary Burns, the niece, by marriage, of Mr. J. P. Morgan. We sit before the fire - very cozy - with a small electric lamp, and two red screens around us to keep the light from the men. There really is not much sitting, for rounds are made every half-hour. Sister Jeffries and I have lunch at midnight, separately, of course, for we cannot both leave the wards at once. During the wee small hours, there is very little to do, for even our five worst cases sleep fairly well. We have cocoa and bread and jam at 4 AM and half an hour later the morning rush begins. You should see Sister Jeffries and me dashing about with bowls and methylated spirit and powder - we have to begin at that unearthly hour or else we should not be through in time for their breakfast at 6 AM. Any one who could see the wards at 4:30 or 5 AM, with the electric lights suddenly on, the men sitting up in bed, washing themselves - and those who have the wherewithal, shaving themselves - wouldn't think there was much poetry in 'nursing the wounded' !! "

November 26, 1914

" Eighty more patients came in on Sunday. Among this lot are one or two cases of bronchitis and pneumonia - from exposure. One of the bronchitis men told me this morning that he has several times been in the trenches for seven or eight days, in water up to his waist - with no chance to get dry.

" We are getting quite used to the rushes now, but we always dread the first few days. They are in terrible condition, most of them, mentally as well as physically - they lie for several days without a word or a smile. They tell us afterwards that it seems like a dream at first just to lie in bed and eat and sleep. There is a special what we call, 'from the front' expression on their faces when they arrive, which fades. They never speak of the horrors they have seen until long after - one would not ask at first.

" Last night I saw an interesting case - one of the worst which came on Sunday. He is in Paget Ward, and one of the American nurses took me in to see him and to help her. He has lost his leg at the knee, and gangrene has set in. When they operated - at the front - they did not leave enough flap of skin to cover the stump. His temperature was 104 last night and he is to be operated on today, the leg taken off at the hip. All last night the Sister had to tightly bandage his leg for fifteen minutes out of every hour, to prevent gangrene spreading. He may get all right, but he may die of septic poisoning."

...

" A man in Paget was telling the Sister that he had been once eleven days without sleep, marching all day and fighting all night. He said he had to kick men who were about him, to keep them awake to fight. He heard men in the trenches praying aloud that they might be shot - in order to be taken to a hospital to get rest. No wonder our men lie like logs when they first come in! It is terrible to think of."

December 23, 1914

" We got in a new lot of eighty wounded a week ago, and many old ones have gone out. Sixteen left from Munsey [Ward] this morning, and tonight at 'breakfast' we heard that a new lot were arriving on the instant. We got 20 of them here in Munsey. Three were fractured femurs, all packed in huge wooden splints from shoulder to heel. One man, a Scotchman of the Black Watch, has been eight weeks in hospital at Boulogne with both legs fractured - a shocking condition after eight weeks ... On my side of the ward there is also a nice boy about twenty, who will never use his right arm again. The shoulder is badly fractured and they had to take out the top of the humerus, as well as lots of small bits of bone. He has been very helpless, but much better now. He has an egg, always scrambled, for his breakfast - I do it and take it to him myself - he does enjoy it, and I wouldn't miss his smile for anything. Another pathetic case is a man who was blown fifty feet into the air, by an exploding shell which killed the two men next to him. You can imagine what condition his nerves are in. He talks constantly in his sleep of France and Belgium."

" Boxing Day - there was a Christmas dinner in the evening for the whole nursing staff in the marble hall - seventy-one of us.

It seemed odd to go to a formal dinner in cap and apron!"

January 5, 1915

" Dr. H. made us laugh tonight by his disgust over one of his wards [i.e. nothing 'interesting'], where out of eight cases new tonight, seven are frost-bite!"

" Am sitting out in the ward as I write, at the Head Sister's desk, between two red screens, listening for calls and giving hot milk. The head case I spoke of is very bad - he is on my side of the ward. He is quite young - and will probably be blind in both eyes, for the bullet went in one eye and out behind the other. He suffers terribly and is completely unstrung. He loves a bit of fussing and begged me to talk with him this morning. We all baby him a lot. Tonight he broke down completely and sat up in bed sobbing, and begging to have his bandage taken off. He kept saying, 'Oh, God, help me to bear my pain.' He had morphia, the dressing changed, and hot drinks, and I have been waiting on him all night long. Every few minutes he sits up and calls for me, and simply clings to one's hand like a baby. It wrings one's heart - for there is no chance, the doctor tells me, of his ever seeing daylight again - and only twenty.

[Later, January 15] ... " The boy does not know the danger that he may never see again, and I dread unspeakably the day when he will have to be told ... Morphia has very little effect, and they don't like to give him much ... He has no family and his home in London is with the mother of his sweetheart, Violet, whose name is tattooed on his arm."

January 21, 1915

" We got a sailor with our last lot of patients - sent to us by mistake! ... He belongs to the little band of seventy - all gunners - chosen from a man-of-war, to man the naval armored trains in Belgium That is how a sailor happened to be fighting on land - and it is the first time it has happened. His cap band is very interesting for that reason - with the letters HMNAT Jellicoe (His Majesty's Naval Armored Train Jellicoe). And he has a medal given by the Belgians, with a picture of the train. Each train is composed of three gun carriages, two powder magazines, and an engine at each end. They run right up to the firing line and can accomplish a lot, beside being able to get away quickly.

" Sir William Osler was here yesterday inspecting the hospital and he very kindly inquired for me.

" I asked a big Seaforth Highlander whether he wanted to go back. He said, 'I don't wish to be like those swankers who say they want to - I'd rather not'; They all ridicule the idea of wanting to go back - and say no sane man could. In that respect this war is different from any other there has ever been. The men all say, 'This isn't war - it's murder.' Most of them are very glad if they can be honorably discharged as physically unfit."

" Dr. H. made us laugh tonight by his disgust over one of his wards [i.e. nothing 'interesting'], where out of eight cases new tonight, seven are frost-bite!"

" Am sitting out in the ward as I write, at the Head Sister's desk, between two red screens, listening for calls and giving hot milk. The head case I spoke of is very bad - he is on my side of the ward. He is quite young - and will probably be blind in both eyes, for the bullet went in one eye and out behind the other. He suffers terribly and is completely unstrung. He loves a bit of fussing and begged me to talk with him this morning. We all baby him a lot. Tonight he broke down completely and sat up in bed sobbing, and begging to have his bandage taken off. He kept saying, 'Oh, God, help me to bear my pain.' He had morphia, the dressing changed, and hot drinks, and I have been waiting on him all night long. Every few minutes he sits up and calls for me, and simply clings to one's hand like a baby. It wrings one's heart - for there is no chance, the doctor tells me, of his ever seeing daylight again - and only twenty.

[Later, January 15] ... " The boy does not know the danger that he may never see again, and I dread unspeakably the day when he will have to be told ... Morphia has very little effect, and they don't like to give him much ... He has no family and his home in London is with the mother of his sweetheart, Violet, whose name is tattooed on his arm."

January 21, 1915

" We got a sailor with our last lot of patients - sent to us by mistake! ... He belongs to the little band of seventy - all gunners - chosen from a man-of-war, to man the naval armored trains in Belgium That is how a sailor happened to be fighting on land - and it is the first time it has happened. His cap band is very interesting for that reason - with the letters HMNAT Jellicoe (His Majesty's Naval Armored Train Jellicoe). And he has a medal given by the Belgians, with a picture of the train. Each train is composed of three gun carriages, two powder magazines, and an engine at each end. They run right up to the firing line and can accomplish a lot, beside being able to get away quickly.

" Sir William Osler was here yesterday inspecting the hospital and he very kindly inquired for me.

" I asked a big Seaforth Highlander whether he wanted to go back. He said, 'I don't wish to be like those swankers who say they want to - I'd rather not'; They all ridicule the idea of wanting to go back - and say no sane man could. In that respect this war is different from any other there has ever been. The men all say, 'This isn't war - it's murder.' Most of them are very glad if they can be honorably discharged as physically unfit."

January 26, 1915

" One man was hit by a hand grenade. He has sixty-seven wounds - all on his head, his back, and arms. One arm is terrible - all the flesh gone - only the two bones left and a hole between. The flesh is slowly growing in around, but it looks like the pictures of the famine in India.

" The worst case in Paget - much talked about - is indescribably awful. The man was shot through the leg - and got the new gas gangrene germ just discovered at the front, and so rare that they know nothing about it yet. He is one of the first men back in England who has it. His leg is in awful condition ... he will probably lose it and they say he may die at any time. It is dreadful to see how he suffers when moved - he screams with pain and it takes five of us to change his draw-sheet. The stench of his dressings fills even this big ward. It is most infectious and we are more than careful."

Please place any metal objects in the container ... Great War technology ...

"We have a Cameron Highlander and a Gordon Highlander in adjoining beds - both their wounds were full of colored bits of their kilts which kept coming out for days. The latter had his operation, and I was again sent up - the bullet could not be found and he had to be taken to the X-ray room. It was fascinating to see the doctors' hands X-rayed as they worked, looking like animated skeletons."

On another occasion, Dexter held and positioned a heavy glass X-ray plate for about an hour during a procedure in the operating room.

February 15, 1915

"The operation done by Dr. S, just after you left [her mother had come across the ocean to visit], was most interesting. It was the first time that the new telephone apparatus for locating bullets and metal substances has been used here. It is quite a new thing, invented here in England some years ago, but only just perfected for practical use. It is simple to look at - a wire attached to the instrument, and the operating doctor and one other man wear metal head-bands with a sort of telephone ear-pieces [sic]. When the instrument touches bone there is no sound, but when it touches metal there is a click. This case which I saw was a bullet deeply embedded in the bone of a man's shoulder - and they were able to get it out much sooner, and with a much smaller incision, than they otherwise could. "

The Depage Hospital, La Panne, Belgium

June to August, 1915

June to August, 1915

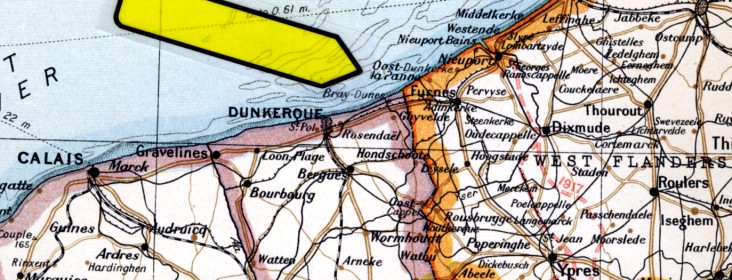

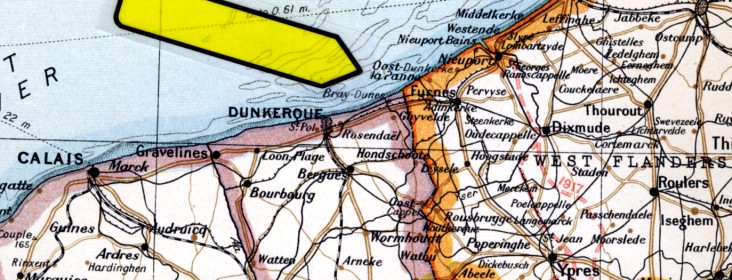

Wanting to get closer to The Front,

Mary Dexter applied to three national Red Cross organizations and

accepted the invitation of the Belgian Red Cross because it was 'at the

front'. She crossed from Folkestone to Calais (there at the right - at

the narrowest part of the channel) with the necessary orders and

permits to get her through France and into the Belgium. She was to be in a military zone under military organization.

Map from 1923

Map from 1923

Mary Dexter during the crossing of the Channel

She was the only

woman on the rough crossing and found a hotel to stay at in Calais until the

arrival of the assigned car ... which was to pick her up for the two hour trip to the Belgian

hospital. A convoy of large grey Belgian

ambulances finally arrived at Calais and she rattled around in the back of one

to the 'Ambulance de l'Ocean' at La Panne.

Slightly misprinted, 'la Panne' can be seen at the end of the arrow.

For scale: It is about 60km from Calais to La Panne.

You can see the proximity of The Front (dashed red line), and Ypres and Passchendaele to the south.

Beyond the Front, along the occupied Belgian coast, were some German U-boat bases

which menaced the critical English Channel supply lines.

Some information on La Panne

from "The Little Corner Never Conquered"

an account of the Red Cross in Belgium.

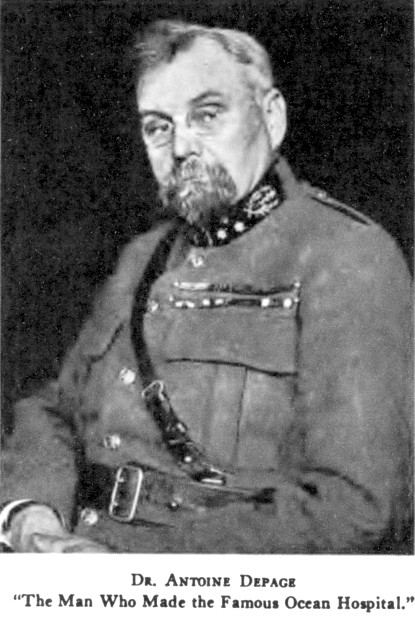

" 'The Hospital of the Queen', 'The

Hospital of Dr. Depage' and the 'Ocean Hospital' were names variously

given to the main hospital of the Belgian Red Cross Society at La Panne

...

" Of the origin Dr. Depage writes as follows:

" The Queen secured for their use the Ocean Hotel property on the

beach. By 1917, there had been added to the original hotel

building at least forty pavilions or barracks, from butchery to chapel,

contributed by various agencies ...

" There was the Institut Marie Depage, and on a lonely sand dune facing the ocean, there was the grave of Marie Depage who raised money for the hospital in America in 1915 and lost her life on the Lusitania coming home. Her body was washed ashore on the coast of Ireland, recovered by Dr. Depage, her husband, and buried at La Panne along the coast just above the hospital ...

" ... at one end of the beach the two modest villas of the King and Queen and their officers, and at the other end toward the trenches - the Ocean Hospital - yet this was the very heart and soul of Belgium, - the real capital of the country."

" Of the origin Dr. Depage writes as follows:

'Toward

the end of November 1914, after the battle of the Yser, I found myself

in Calais. I had come to organize there the hospital 'Jeanne

d'Arc' with the funds put at my disposal by the Belgian Red Cross. Queen Elisabeth [of Belgium] in

the course of a visit which she had made to our wounded, proposed to me

that we establish at La Panne a new hospital which she desired to see

created nearer the front and upon Belgian territory.

'At the moment, with the exception of the Belgian Field Hospital, which we owe to the generosity of the English and which was later transferred to Hoogstade, our only surgical hospital in the zone of the armies was at Furnes. It was served by religious sisters whose good will could not supply the lack of professional training. Her Majesty understood the great advantage that there would be in giving competent surgical attention to the severely wounded before an evacuation which meant a long journey by automobile or railway train. I accepted Her Majesty's proposition with enthusiasm as I was sure that in realizing her ideals, we would be able to make a noble contribution to the care of our wounded.'

'At the moment, with the exception of the Belgian Field Hospital, which we owe to the generosity of the English and which was later transferred to Hoogstade, our only surgical hospital in the zone of the armies was at Furnes. It was served by religious sisters whose good will could not supply the lack of professional training. Her Majesty understood the great advantage that there would be in giving competent surgical attention to the severely wounded before an evacuation which meant a long journey by automobile or railway train. I accepted Her Majesty's proposition with enthusiasm as I was sure that in realizing her ideals, we would be able to make a noble contribution to the care of our wounded.'

" There was the Institut Marie Depage, and on a lonely sand dune facing the ocean, there was the grave of Marie Depage who raised money for the hospital in America in 1915 and lost her life on the Lusitania coming home. Her body was washed ashore on the coast of Ireland, recovered by Dr. Depage, her husband, and buried at La Panne along the coast just above the hospital ...

" ... at one end of the beach the two modest villas of the King and Queen and their officers, and at the other end toward the trenches - the Ocean Hospital - yet this was the very heart and soul of Belgium, - the real capital of the country."

" Antoine Depage was physically and mentally a big man. He was of humble origin and seemed to have the strength of generations of Vikings behind him. He had a great frame and an iron will. He knew surgery and medicine and hospitals and he knew also what other countries had discovered and the men who were doing things ...

" The King settled in short order the question of the military status of Belgian Red Cross doctors. The entire Red Cross was taken into the military establishment, except the contributed funds which were left in charge of the executive committee.

" The doctors were commissioned in the army. Dr. Depage became a Colonel. He wore the uniform, and he had the insignia, but he never thought of himself as anything but Head Surgeon, and this was his strength and his weakness. He paid scant attention to the spirit of orders which interfered - he never followed along the paths of army red tape, he made some of the military men almost froth at the mouth with rage, and yet he was too big and important and valuable to be taken out and shot at sunrise. When real tension resulted, there was the little Queen with some common sense solution, or the King with a suggestion which Depage, out of both love and loyalty would be quick to accept."

A New York doctor summarized:

" Depage is a great man. Some of them hate him but they can't do without him. Back him up. He may be extravagant but he is extravagant to save life and he is able and honest."

* * *

Mary Dexter fills in details of her work ...June 30, 1915

" The work is very hard here, and most interesting ... Each ward holds one hundred and twenty beds. I have been given twenty beds of my own to be responsible for. Also one helps with dressings all over the ward.

" One never stops - there are no chairs, and if there were they would be utterly superfluous. There is a theatre between the two wards, with four operating-tables. And it is one ceaseless round of operations - the brancardiers (orderlies) bringing in one case, fetching him out, carrying in the next - without stopping - all the mornings and most of the afternoons. I have already been sent in with several patients. The four tables are going hard all the time - and such cases! If one sat down and thought it would be unbearable, but one never thinks - it is the only way.

" We are a polyglot crowd - Belgian, French, Danish, English, Scotch, American, Canadian - and very likely others. This is only my second day, and I have yet much to discover."

July 7, 1915

" Splendid news - I have received a draft for twenty pounds from the St. Timothy's Alumnae, voted by them at the meeting at Baltimore. Will you cash it and send ether as soon as possible? - we are needing it so much. When your cable came yesterday afternoon, it was brought to me in the theatre - where I was holding down a patient, and steeped in blood - I couldn't read it for ages. I don't describe any wounds, because one just couldn't here - they are all too awful. I couldn't ever tell what I have seen in the theatre here."

...

" All the Canadians (whose day is July 1st) and all the Americans (for the Fourth) were invited two nights ago to the big salon and presented with flowers by the Belgians - Dr. Depage among the rest. There were speeches and cheers and so on. Yesterday afternoon Dr. Depage asked all us Americans to tea at his villa, to celebrate."

Isolation Villa, July 14, 1915

" If I came out here for experience I am certainly getting it! Not every one could be threatened with a diphtheritic throat and display a rash which baffled all the doctors, and be carried on a stretcher to the Isolation Villa in the sand dunes - all within five miles of the trenches and within sound of the German guns!"

Wimereux, France, July 24, 1915

[Sister Vera, Dexter's Australian mentor at Paignton, was to take Dexter to England for a rest as soon as she was able to travel.]

" Matron has written from La Panne that she wants Sister Vera and me - and in that case Vera would probably be head of a ward. Although she is only my age, she has done nursing for eight or nine years, and has been a Matron."

Wimereux, July 26, 1915

" Sister Vera is resigning from her hospital and I find that it is on my account, in order to take me to England. To tell the honest truth, my case seems to have been rather misunderstood at La Panne. Here the opinion is that what I really had was something serious - on account of complications which have since appeared.

" Editor's note: Illness diagnosed later by London physicians as scarlet fever."

Before continuing with the second half of Mary Dexter's war experiences

... here is a quick Canadian connection to this area of Belgium ...

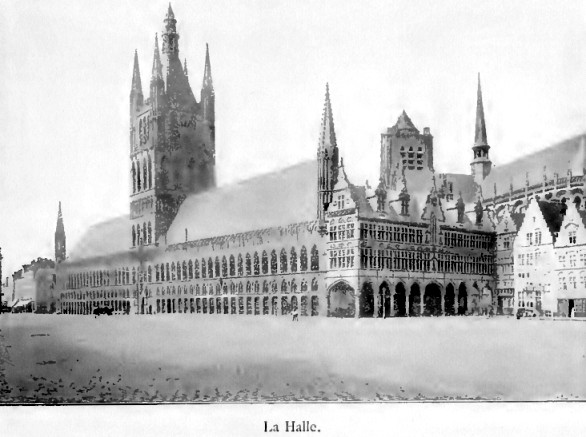

On the wall of the Senate Chamber in the Canadian Parliament Buildings is a painting of this building.

Behind the structure is painted a beautiful blue sky with white clouds

The Cloth Hall at Ypres, Belgium was built between 1260 and 1304 CE, as the centre of the region's prosperous trade in fabrics and lace.

... here is a quick Canadian connection to this area of Belgium ...

On the wall of the Senate Chamber in the Canadian Parliament Buildings is a painting of this building.

Behind the structure is painted a beautiful blue sky with white clouds

The Cloth Hall at Ypres, Belgium was built between 1260 and 1304 CE, as the centre of the region's prosperous trade in fabrics and lace.

From a 1908 tour book.

The Ypres Salient ('bulge') was a protective pocket around Ypres

which was fiercely held and defended by the British Expeditionary Force

... and later by Canadian units among others.

Here is that Depage Hospital map again with Ypres at the bottom right edge,

and you can see the Ypres Salient around the eastern side of the city.

(Ypres is about 35 kilometres ... from ... La Panne at the yellow arrow)

The Battle of Passchendaele (a village just to the northeast) is 'officially' known as 'The Third Battle of Ypres'.

Church spires, towers, high ground and aircraft were tactically important in the Great War ...

because the military used them to keep an eye on the enemy, and to provide aiming commands for indirect artillery fire.

Well, wouldn't you know it - something happened to the 600 year old Cloth Hall and its tower

... during the First Battle of Ypres in late October, early November 1914 ...

The Germans had been active up to this point in the shelling and aerial bombing of Belgian cities and towns,

and they were in military control when the ancient library at Louvain, Belgium was burned ...

The British and French were also fighting in the area ...

A French Postcard

During the Great War, Canadian forces spent a lot of time around Ypres in the presence of the Cloth Hall rubble.

The ruins were painted by James Kerr-Lawson in 1919,

and his very large painting, and other similar Great War pieces,

were intended for a special Great War memorial building back in Canada.

The memorial edifice was never built and the paintings ended up in the Senate.

The ruins were painted by James Kerr-Lawson in 1919,

and his very large painting, and other similar Great War pieces,

were intended for a special Great War memorial building back in Canada.

The memorial edifice was never built and the paintings ended up in the Senate.