Many are old enough to remember

the time when persons, correspondence, and merchandise were transported

from place to place in this country by stage-coaches, vans, and

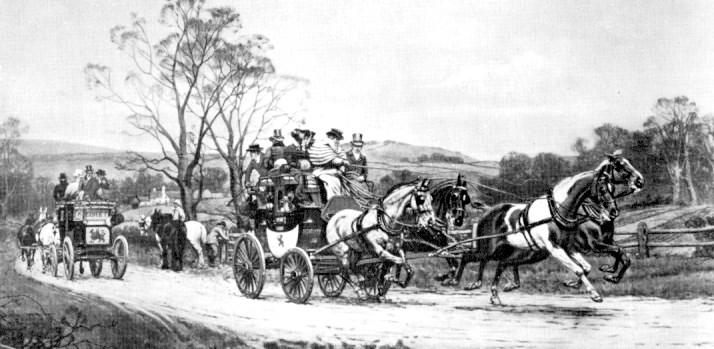

waggons. In those days the fast-coach, with its team of spanking

blood-horses, and its bluff driver, with broad-brimmed hat and drab

box-coat, from which a dozen capes were pendant, who 'handled the

ribbons' with such consummate art, could pick a fly from the ear of the

off-leader, and turn into the gateway at Charing Cross with the

precision of a geometrician, were the topics of the unbounded

admiration of the traveller. Certain coaches obtained a special

celebrity and favour with the public. We cannot forget how the eye of

the traveller glistened when he mentioned the Brighton 'Age', the

Glasgow 'Mail', the Shrewsbury 'Wonder' or the Exeter 'Defiance' - the

'Age' which made its trip in five hours, and the 'Defiance which

acquired its fame by completing the journey between London and Exeter

in less than thirty hours.

The rapid circulation of intelligence was also the boast of those times. How foreigners stared when told that the news of each afternoon formed a topic of conversation at tea-tables the same evening, twenty miles from London, and that the morning journals, still damp from the press, were served at breakfast within a radius of thirty miles, as early as the frequenters of the London clubs received them.

New let us imagine that some profound thinker, deeply versed in the resources of Science at that epoch, were to have gravely predicted that the generation existing then and there would live to see all these admirable performances become obsolete, and consigned to the history of the past; that they would live to regard such vehicles as the 'Age' and 'Defiance' as clumsy expedients, and their celerity such as to satisfy those alone who were in a backward state of civilisation !

Let us imagine that such a person were to affirm that his contemporaries would live to see a coach like the 'Defiance' making its trip between London and Exeter, not in thirty, but in five hours and drawn, not by 200 blood-horses, but by a moderate sized stove and four bushels of coals !

Let us further imagine the same sagacious individual to predict that his contemporaries would live to see a building erected in the centre of London, in the cellars of which machinery would be provided for the fabrication of artificial lightning, which should be supplied to order, at a fixed price, in any quantity required, and of any prescribed force: that conductors would be carried from this building to all parts of the country, along which such lightning should be sent at will; that in the attics of this same building would be provided certain small instruments like barrel-organs or pianofortes; that by means of these instruments, the aforesaid lightning should, at the will and pleasure of those in charge of them, deliver messages at any part of Europe, from St. Petersburgh to Naples; and, in fine, that answers to such messages should be received instantaneously, and by like means: that in this same building offices should be provided, where any lady or gentleman might enter, at any hour, and for a few shillings send a message by lightning to Paris or Vienna, and by waiting for a few moments, receive an answer !

The rapid circulation of intelligence was also the boast of those times. How foreigners stared when told that the news of each afternoon formed a topic of conversation at tea-tables the same evening, twenty miles from London, and that the morning journals, still damp from the press, were served at breakfast within a radius of thirty miles, as early as the frequenters of the London clubs received them.

New let us imagine that some profound thinker, deeply versed in the resources of Science at that epoch, were to have gravely predicted that the generation existing then and there would live to see all these admirable performances become obsolete, and consigned to the history of the past; that they would live to regard such vehicles as the 'Age' and 'Defiance' as clumsy expedients, and their celerity such as to satisfy those alone who were in a backward state of civilisation !

Let us imagine that such a person were to affirm that his contemporaries would live to see a coach like the 'Defiance' making its trip between London and Exeter, not in thirty, but in five hours and drawn, not by 200 blood-horses, but by a moderate sized stove and four bushels of coals !

Let us further imagine the same sagacious individual to predict that his contemporaries would live to see a building erected in the centre of London, in the cellars of which machinery would be provided for the fabrication of artificial lightning, which should be supplied to order, at a fixed price, in any quantity required, and of any prescribed force: that conductors would be carried from this building to all parts of the country, along which such lightning should be sent at will; that in the attics of this same building would be provided certain small instruments like barrel-organs or pianofortes; that by means of these instruments, the aforesaid lightning should, at the will and pleasure of those in charge of them, deliver messages at any part of Europe, from St. Petersburgh to Naples; and, in fine, that answers to such messages should be received instantaneously, and by like means: that in this same building offices should be provided, where any lady or gentleman might enter, at any hour, and for a few shillings send a message by lightning to Paris or Vienna, and by waiting for a few moments, receive an answer !

Overcoming distance ... the early 1800s edition

A source from the late 1800s

suggests that the Golden Age of the mail coaches was 1824 to 1848.  Here two mail coaches pass each other on the Leeds-York Road. At the left is the 'Comet' and making up time is the 'High-flyer'. The other traffic has appropriately yielded the right of way. Plodding horse-drawn vans

and wagons were more economical when purchasing intercity travel, particularly if moving large items. Before

railways, nothing had a faster schedule than the Mail Coaches. The two

paid workers are the driver (with the capes) and the last man on top -

the postal guard.

The horses were generally changed at 'inn and stable' establishments about every 10 miles. If the distance London to Glasgow is about 400 miles, for example, and teams of horses were changed only every 15 miles ... one coach trip between the centres required over 100 strong, fast horses. The supplying of young replacement horses, stabling, feeding & watering, harnessing, etc. would have been relatively costly for the operators ... but the 'inn-stable economy' along the highway corridors through the countryside would have benefitted. For the important mail coaches, the horses had better be harnessed and ready at every stable for a quick change! You can barely see the straight, valveless 'post horn' in the postal guard's right hand. The postal guard stayed with the mail trunk at the rear and he used the post horn to 'call ahead' so the mail bags could be exchanged while moving if possible. The post horn could also be used to warn other traffic to yield the right of way. Night encounters with the rushing unlighted coaches were often deadly for pedestrians. At least at the beginning, the coaches were often owned and operated by contractors (who often owned a fleet) ... while the postal guard was a postal employee who had ready access to firearms to protect his cargo. Toll roads - the rights to which were auctioned off to yet other private sector contractors who maintained them and took the tolls - were the most common form of highway used. A turnpike (the wooden pole blocking the road beside the toll house) without an attendant ready to open it smartly for the approaching mail coach ... would result in a fine being levied on the contractor for delaying the mail. A nostalgic account suggests that riding the passenger seats on top of the coach was preferable to the bruises and 'human intimacy' one would experience if riding inside the coach. Certain 'influential gentlemen' would sometimes prevail upon the driver to let them drive. Relinquishing the 'four in hand' ... by a professional coachman to let's say, a barrister or a Member of Parliament, was generally something passengers would dread. Horses apparently have the potential to get kind of giddy and loopy and run out of control with your rig attached to them ... until you settle them down again, or the coach crashes ... whichever comes first. Passenger breakfast and supper would generally be quickly taken at the 'inn-stable' wayside hospitality complexes on the long runs ... with drivers changing off at the same time. A weary, shaken-up passenger staying the night at the wayside inn as the coach departed ... made the dangerous assumption that the next day's coach would have a vacant seat available so they could continue their journey. No telegraphs, telephones, or reservation systems existed ... the mail was the fastest thing in communications, remember. Considering all the efforts and wayside infrastructure devoted to the mail coach system to make it fast ... the maximum average speed for mail coach routes, even during the Golden Age, was 10 mph. Coach enthusiasts mourned the lost thunder and fury of the horses and mail coach when the railways replaced them. Since then these icons of pre-industrial society have been most commonly spotted on tins containing candies and cookies. The swampy barge canals and early sooty railways do not evoke the same sweet nostalgia. |

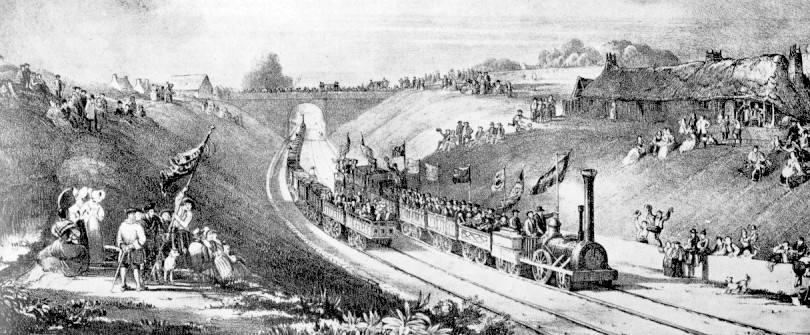

1831 - Glasgow and Garnkirk Railway

(showing two 'moderate sized stoves and eight bushels of coals')  With

two tracks - one for each direction - early railways could run by

daylight with little danger of collision. Note that compared to the

mail coaches, there were fewer employees per passenger-mile, or per

ton-mile of cargo. Back in the stable, the iron horses ate nothing ...

just a little tallow to soothe their joints before their next run. Some

of them worked on for 50 years.

"Stop now ... before it is too late! ...

I predict ... Someday Your new 'science of economics' will be held dearer by Man than God's Green Earth. We will burn so much coal that the Earth will heat and the seas will rise ... the poles will melt, and deserts will spread upon the land ..." "Burn the witch! Burn the witch!" ... sorry wrong era ... Now see here! ... This is Progress! ... The Prosperity of the Nation will rise.

Who knows what great inventions and wonders are yet to come! They shall be a boon to all Mankind! ... Average speed and the national continuity of the railway network were still problems to be solved in Britain and across Europe ... but they'd have them solved before long. The single proprietor coach companies and toll road trusts were giving way to new capital-intensive transportation companies - the latter issued paper securities to investors to finance their vast and expensive plant and equipment. The government supported them in their requests to build their rights-of-way across private land.  Britons prostrate themselves before the 'Railway Juggernaut of 1845' from 'Punch'. The new technology had been embraced by society. Surely every public company ending with the word 'railway' would be an excellent investment ! |

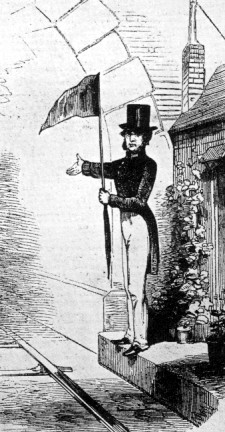

'Telegraphing ... farther and farther'

Here is the early British railway signal for 'all clear' or 'proceed' or 'highball'.

The signalman knows that the tunnel ahead is clear.

The engineer sees this signal at a distance and knows he can run at normal speed

until he encounters the next signalman at the distant end of the tunnel.

Near the end of the tunnel he will be signalled for the next 'block' of track

by the next signalman.

During this era, physically-fit people bragged that the trains were slow enough ...

that they could disembark at any spot they wanted ... i.e. between stations.

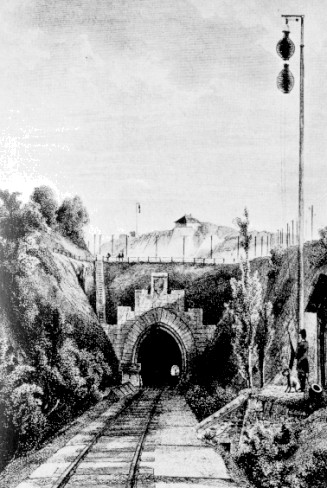

Signaling over a longer distance.

Signalling when two tracks reduce to one track.

The farther locomotive engineers can see signals ... and the better signals connect with other signals down the line ...

the faster trains can go and the more efficient the transportation system becomes.

Here is a block signal circa 1845 on the line between Trnava and Bratislava in today's Slovakia.

It seems likely that the signal ... and its distant mate on top of the mountain ... protect the tunnel 'block' from both ends.

Probably double track reduced to single track here to avoid the expense of a double track tunnel.

It seems possible that these signal operators may work like flagmen at a 'two-lane to one-lane' road construction site today ... that is ...

If one signal shows 'stop' to approaching traffic ... the other may then be turned to 'slow' ... to allow traffic through the single available lane.

[e.g. mountaintop sees train approaching its end & lowers to stop, here ball is lowered to stop, then mountaintop raises as 'proceed']

If trains are run by night, these ball-shaped signals can be illuminated by lanterns.

If either signal becomes defective or 'de-energized' in any way ...

that is, the lantern goes out, or the highball falls to the ground ...

then the proceed signal is no longer visible.

An essential element in the fail-safe design of modern railway signals is ...

'a signal defect or failure indicates "stop" or "operate with extreme caution per the rules" '

(Railroaders today, having never seen one during their careers, still say ' highball! ' as an affirmation that they are ready to depart)

... and farther still ...

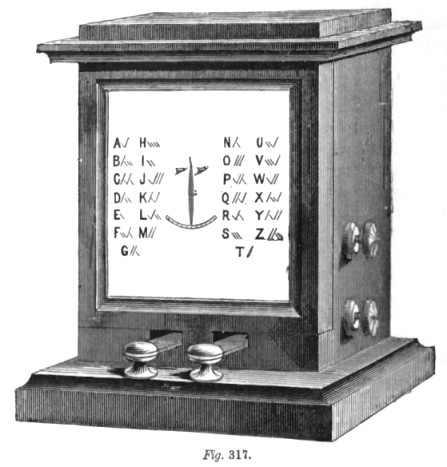

Wheatstone and Cooke

As mentioned on the 'Telegraph Part 1' page ...

The needle telegraph (displaying signals through the deflections of one to five needles)

was developed in Britain by Wheatstone and Cooke.

The code is displayed on the machine ... so 'A' is 'short to the left, long to the right'.

To send your very own deflections ... use the two levers at the front.

One contemporary reference stated that boys in their late teens

made the best and fastest needle telegraph operators.

Sir Charles Wheatstone

Inventor of the Telegraph

(yes, another one)

Charles Wheatstone 1802-1875

was the son of a musical instrument vendor who became a professor and scientist

with a wide variety of interests, including electrical theory. He was

one of the few who came to understand Ohm's Law during that period, and eventually how to

make electromagnets for telegraphs ... In the terminology of the day he

was an 'electrician' ... today, he'd be an 'electrical guru'.

William Fothergill Cooke 1806-1879 was the son of a medical doctor and professor of anatomy. William's working life began as a military officer with the East India Army. He left this to pursue a career in medicine and had a talent for making precise wax models of dissections. During his medical studies in Heidelberg (in today's Germany) he came upon a model of Schilling's telegraph and became enthralled with the technology. Cooke quickly put together his own three-needle telegraph and later added features such as an alarm signal. Not entirely satisfied with his invention, he talked to Faraday and was eventually referred to Wheatstone.

Wheatstone had been working on his own telegraph! Cooke and Wheatstone worked together, got a patent on their telegraph and formed a partnership in 1837. Wheatstone used the latest scientific knowledge to perfect the technology and Cooke handled administration and promotion. Cooke was a much more confident public speaker than Wheatstone and had the conviction that the telegraph could be profitably employed to efficiently manage railway traffic ... particularly on single track railways. In 1845 the Electric Telegraph Company was registered and Wheatstone received 33,000 Pounds as a result of his partnership with Cooke.

Inevitably ... there was the 'usual telegraph dispute' over which of the two 'invented the telegraph'. Brunel, their mutual acquaintance from the earliest railway telegraph trials, was brought in to arbitrate and he eventually concluded that they both had.

Wheatstone was also interested in submarine telegraph cable which would soon draw the whole world closer together. In 1845 he suggested that gutta percha be used to electrically insulate undersea cable and protect it from corrosion. Unlike elastic rubber, this natural tree-rubbery-stuff coated the cable well and held up under sea water. Gutta percha made undersea cables viable.

William Fothergill Cooke 1806-1879 was the son of a medical doctor and professor of anatomy. William's working life began as a military officer with the East India Army. He left this to pursue a career in medicine and had a talent for making precise wax models of dissections. During his medical studies in Heidelberg (in today's Germany) he came upon a model of Schilling's telegraph and became enthralled with the technology. Cooke quickly put together his own three-needle telegraph and later added features such as an alarm signal. Not entirely satisfied with his invention, he talked to Faraday and was eventually referred to Wheatstone.

Wheatstone had been working on his own telegraph! Cooke and Wheatstone worked together, got a patent on their telegraph and formed a partnership in 1837. Wheatstone used the latest scientific knowledge to perfect the technology and Cooke handled administration and promotion. Cooke was a much more confident public speaker than Wheatstone and had the conviction that the telegraph could be profitably employed to efficiently manage railway traffic ... particularly on single track railways. In 1845 the Electric Telegraph Company was registered and Wheatstone received 33,000 Pounds as a result of his partnership with Cooke.

Inevitably ... there was the 'usual telegraph dispute' over which of the two 'invented the telegraph'. Brunel, their mutual acquaintance from the earliest railway telegraph trials, was brought in to arbitrate and he eventually concluded that they both had.

Wheatstone was also interested in submarine telegraph cable which would soon draw the whole world closer together. In 1845 he suggested that gutta percha be used to electrically insulate undersea cable and protect it from corrosion. Unlike elastic rubber, this natural tree-rubbery-stuff coated the cable well and held up under sea water. Gutta percha made undersea cables viable.

During this era of rapidly advancing technology, Palmerston stated that ...

" ... a time [is] coming when a

minister might be asked in Parliament if war had broken out in India,

and [he] would reply, 'Wait a minute; I'll just telegraph to the

Governor-General, and let you know.' "

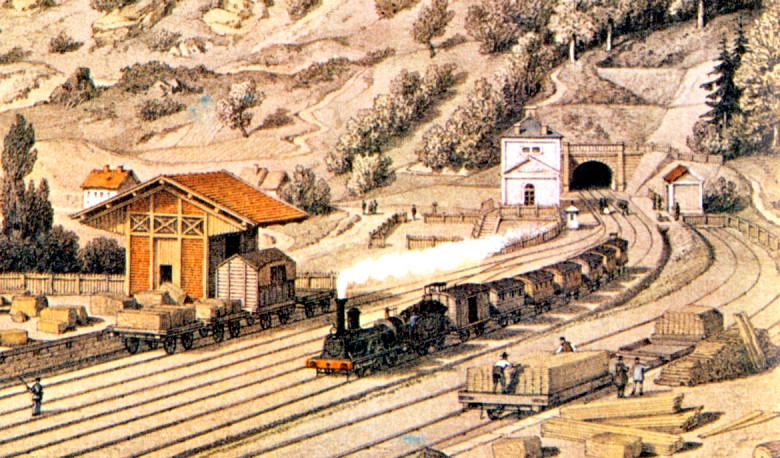

Meanwhile, on the European railways in the mid-1800s ...

Running Strasbourg to Paris in the 1850s, a train makes a passenger station stop and then departs Lutzelbourg.

An example of an 'intermediate station' with a 'station master' is the white building to the left of the tunnel portal.

At the left foreground, cut building stone is loaded onto flat cars, to the right, lumber is being loaded.

At the lower left corner, a signalman is giving a 'proceed' signal as the train runs to the next station on the line.

(Blame not this little engine and these modest economic activities ... half of all coal consumption - ever - has happened since 1972)

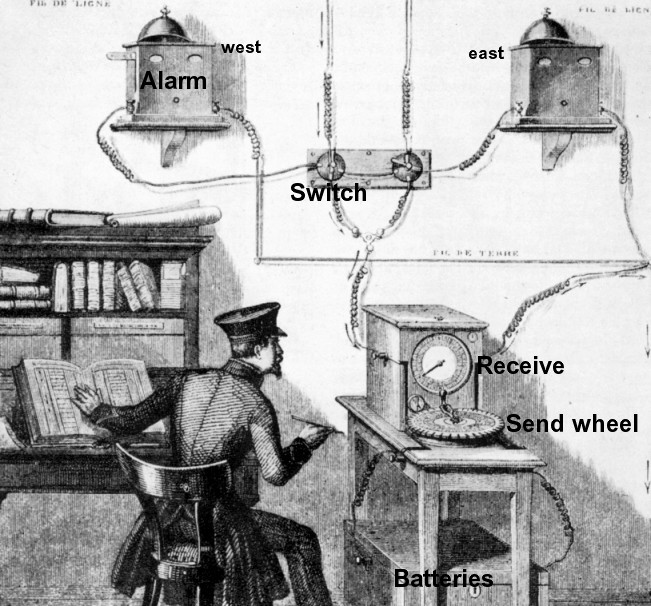

The 'most typical' early

European, electromagnetic telegraph installation, for railway traffic control ... is at a small

station located between two large terminals. Typically, a 'station master'

or his delegate would negotiate the use of the main track(s) with the

two stations on either side. (This contrasts with the North

American centralized train dispatcher 'general' directly commanding his trains through his

telegraph operator 'lieutenants' in the field)

This intermediate station with a station master idea conveniently allows people with little hobby websites to avoid going over the more complex systems needed at large, busy European terminals to support telegraph operations. There were all kinds of non-standard clever inventions used all across Europe.

In the mid-1800s many British railways were using deflecting telegraph needles or signal bells to communicate that the next station down the line had just received the local station's train ... therefore, the line was now clear. Similarly, if the distant station master wanted to send a train toward the local station master's station, they would generally verify that he was ready to receive it.

With these British systems, in some cases, a code of needle deflections was used to send messages 'CAN YOU TAKE AN EASTBOUND' for example.

In other cases, to make up another example ... a signal bell dedicated to 'the next station to the east' would right 6 times ... their particular signal for 'the westbound you sent has just arrived'.

On the early railways, spare locomotives had been used before the telegraph to ... go looking for trains which were overdue and possibly in trouble ... as 'runners' transporting important messages and paperwork between stations as needed or scheduled.

This intermediate station with a station master idea conveniently allows people with little hobby websites to avoid going over the more complex systems needed at large, busy European terminals to support telegraph operations. There were all kinds of non-standard clever inventions used all across Europe.

In the mid-1800s many British railways were using deflecting telegraph needles or signal bells to communicate that the next station down the line had just received the local station's train ... therefore, the line was now clear. Similarly, if the distant station master wanted to send a train toward the local station master's station, they would generally verify that he was ready to receive it.

With these British systems, in some cases, a code of needle deflections was used to send messages 'CAN YOU TAKE AN EASTBOUND' for example.

In other cases, to make up another example ... a signal bell dedicated to 'the next station to the east' would right 6 times ... their particular signal for 'the westbound you sent has just arrived'.

On the early railways, spare locomotives had been used before the telegraph to ... go looking for trains which were overdue and possibly in trouble ... as 'runners' transporting important messages and paperwork between stations as needed or scheduled.

The French inventors were busy too...

In Telegraph Part 1, France's

system of 'aerial telegraphs' - mechanical signalling semaphore arms on

high ground - was illustrated. It 'wasn't bust' ... so for official purposes, this reliable

system was retained until electromagnetic telegraphs were more

practical and robust. A comprehensive French reference from 1872 gives

most of the credit for this refinement to the Briton Wheatstone, rather

than to the American Morse. Consistent with the 'if it isn't bust ...' idea, some of the first French electromagnetic

telegraphs visually reproduced the same 'arm position code' used on France's

old mechanical semaphores.

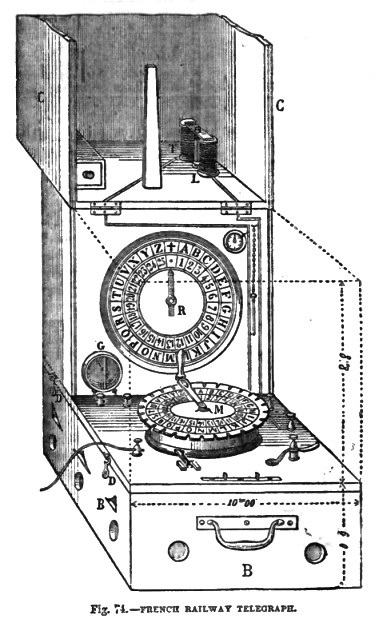

Morse (US) had clacking magnets and inscribed register tapes, Wheatstone (Britain) had little flippy needles, and this is the French railway telegraph ...

Morse (US) had clacking magnets and inscribed register tapes, Wheatstone (Britain) had little flippy needles, and this is the French railway telegraph ...

So let's pretend we are facing north, and the tracks are westbound and eastbound.

The station agent has the switches arranged so that ...

1) West station is connected to the telegraph.

2) East station is connected to to the alarm ... 'call waiting'.

After the electrical potential from another station actuates the equipment,

the current drains off into the ground wire attached to buried metal plates or utility pipes.

* * *

Here is a portable version of the French telegraph for emergency trackside use.

The general operation is similar to the fixed station shown above.

To use:

Connect to overhead wire and ground the set to a rail.

Batteries are behind 'B'.

Dial clockwise to the character desired on wheel 'M' and send ... keep going clockwise with your characters.

A precise clockwork mechanism in the box does most of the magic.

Your answer should spell itself out, letter by letter, on the wheel 'R'.

To imagine this in operation ...

Think of how an old ship's telegraph works:

Personnel on the ship's bridge shift the selector back and forth, ringing, and stopping on 'full speed ahead' ...

The engine room telegraph indicator shifts back and forth, ringing, and stopping on 'full speed ahead'.

This French railway telegraph could send about 40 letters per minute.

This telegraph was thought to be

easy enough to use that semi-literate people

(liberte-egalite-fraternite R us) could send a message when required.

The situation was foreseen that a highly-trained station agent would

not always be around, so a less-skilled attendant might have to send or

receive information.

An interesting 1872 observation from France was that with the privacy and secrecy most business people in America demanded for their personal and business affairs, this simple system would be inappropriate and unacceptable in US railway stations.

To support this last idea, I have read that it often took American Morse personnel about two years to become really proficient at fast interpretation and sending. So to know everyone's secrets, one had to belong to the Morse Priesthood through apprenticeship.

The French state electromagnetic telegraph system also used different equipment which sent and received faster. However, 40 letters per minute was apparently good enough to run a railway back then : 'TELL MAURICE THE CHEESE IS ON THE TRAIN'

An interesting 1872 observation from France was that with the privacy and secrecy most business people in America demanded for their personal and business affairs, this simple system would be inappropriate and unacceptable in US railway stations.

To support this last idea, I have read that it often took American Morse personnel about two years to become really proficient at fast interpretation and sending. So to know everyone's secrets, one had to belong to the Morse Priesthood through apprenticeship.

The French state electromagnetic telegraph system also used different equipment which sent and received faster. However, 40 letters per minute was apparently good enough to run a railway back then : 'TELL MAURICE THE CHEESE IS ON THE TRAIN'

* * *

So simple ... a conductor can use it.

(a joke for locomotive engineers)

The dark clouds are rolling in.

The vultures are circling over your train.

In fact, emergency use of this portable telegraph by train crews was discontinued

because it introduced too many uncontrolled variables to the telegraph system.

* * *

While a French conductor of the mid-1800s had to take "Shanks' Locomotive"

to the next point of communication after his portable telegraph was taken away ...

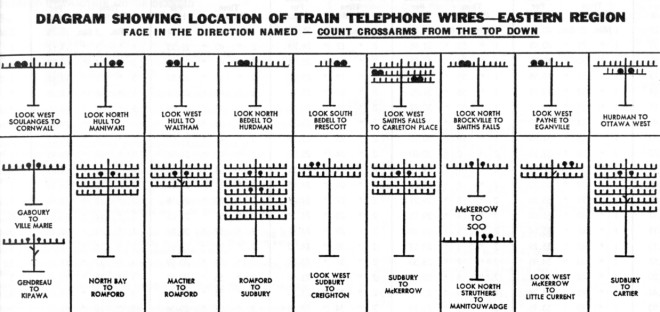

Tapping trackside wires was still the prescribed way to connect with a higher power 100 years later.

Between roughly 1920 and 1980 in Canada, train crew were provided with emergency equipment to telephone the dispatcher ...

if they were not near a station or a wayside telephone when Immobilizing Big Trouble struck.

In mountainous areas, diesel locomotive FM radios could not always reach the nearest radio towers until the 1980s.

Above is part of a diagram from a 1966 employee timetable.